Norm Eisen meets Václav Havel, former president of the Czech Republic, in October 2011.Forum 2000

Norm Eisen is best known these days as one of the leading critics of President Donald Trump. He chairs the board of Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a.k.a. CREW, a nonprofit watchdog outfit that has filed numerous lawsuits targeting alleged ethics violations within the Trump administration. Eisen, who served as ethics czar in the Obama administration, has earned much attention as a passionate and ebullient good-government crusader on the Trump beat. Yet he has another side to his professional life.

Eisen was US ambassador to the Czech Republic from 2011 to 2014. While in Prague, he lived in what is considered to be the most impressive and luxurious American ambassadorial residence in the world, a palace built after World War I by a Jewish financial baron named Otto Petschek. During his stint as ambassador, Eisen fell in love with the building and the stories of its previous occupants, which included a German general during the Nazi occupation (who helped save Prague from annihilation) and two previous US ambassadors—one was former child actor Shirley Temple Black—who each witnessed and participated in seismic geopolitical shifts during their tenures. While living in what was once the home of the richest Jew in Czechoslovakia, Eisen was mindful that his mother, a Holocaust survivor, had once been one of the poorest Jews in the country. His appointment as ambassador to the Czech Republic was something of a grand capstone for his own family tale.

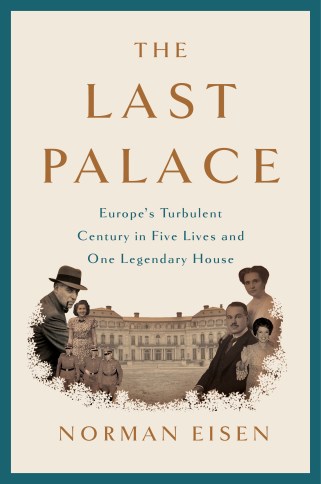

So what’s a fellow to do with all this material? Obviously, write a book. Eisen has produced a riveting and elegantly composed history of this mansion and its inhabitants: The Last Palace: Europe’s Turbulent Century in Five Lives and One Legendary House (Crown). It’s a stunning narrative of personal dramas—juxtaposed against his mother’s story—that capture the sweep of European history in the last century. At first glance, the book, which comes out on Tuesday, might seem like quite a departure from Eisen’s current work within the crazy news cycles of the Trump years. But at the heart of his storytelling—and his do-goodism—is what he describes as a desire to protect and advance the cause of liberal democracy. The Last Palace is both a wonderful distraction from the dog-fights of the moment and an important reminder that democratic norms do not survive on their own. They must constantly be fought for.

Eisen spoke to Mother Jones about the book and why this particular slice of the past is relevant today.

Mother Jones: Norm, you are known for being a critic who ferrets out the corruption of the Trump administration. So why in the middle of all that did you decide to devote time to telling the story of one big house in Prague?

Norm Eisen: Every crusading critic comes from someplace. With the almost 300 litigation matters that we’ve opened up at CREW—not to mention my scholarship and my writing—I’m driven by the events of the past century that flung my family out of Europe and onto the shores of the United States, which embraced us. I wrote this book because I wanted Americans to understand that the challenges that our democracy face are not unique. Both sides of the Atlantic, in Europe and the United States, have faced down far bigger threats than Donald Trump—and even the Trump-Putin axis—over the past 100 years. We’ve faced down those threats and we’ve won. I want people to take those threats seriously, and this threat we’re facing now is serious. It’s dead serious! But there have been larger ones. And if we learn from history—you know, history doesn’t repeat but it does rhyme—we can also learn, put in context, and win, just as democracy has beaten illiberalism before.

MJ: How long have you been working on this book? Was it hard to live in the past while being so engaged in the present?

NE: I started working on the book when I came back from Prague because I had heard the incredible stories of the people in my house: the Jewish optimistic pro-American builder of the house after World War I; the Wehrmacht general representing Nazi Germany who occupied the house; the American ambassador who fought the Cold War; his successor, the movie star envoy who helped win it. Their stories were fascinating in their own right. Their lives and loves, their successes, their heartbreak, their fights with their spouses or their kids. But they also told this drama of democracy. And then there was the fifth story, which was my mother’s story. She was born in the same year the ground was broken for the palace. I didn’t want those stories and everything I had in my head about the people, the house, and the century—and my mother’s story—I didn’t want them to be lost. That’s why I started writing the book when I got back from Prague.

In the middle of writing the book, the thing—the specter, the shadow, the eclipse that has happened over and over again in the past century—happened here. And that was Trump’s ascent. We’ve seen his ilk in power in Europe before, never in this century in the United States. I had thought about dropping the book and just doing my accountability work and scholarship, but I had already accepted the advance. And Trump’s election turbocharged the project for me. I now had a mission: to convince people the Trump threat was serious and to reassure people that we could fight him and win.

MJ: Your book does describe the rise of authoritarianism and fascism in Europe, particularly what happened in Czechoslovakia after the Nazi invasion. These days some Trump critics throw the “F-word” about—maybe too loosely—and point to what they say are early warning signs. Do you see a creeping authoritarianism here and reason to fear that it could lead to something much worse?

NE: I do think that we are facing a president who has profound autocratic tendencies. He’s hostile to each of the five core freedoms, which I believe define the liberal project: personal freedom, political freedom, press freedom, market freedom, and judicial freedom. He does have that in common with autocrats. But we don’t know how far his natural hostility would go. There’s been enormous pushback in each of those areas by individuals and by the system. His own executive branch—the branch he heads!—is his greatest adversary. Congress, which is supposed to be a check and balance, is supine. So you’ve seen the executive branch in the form of prosecutors—and the judiciary—working as a check and balance on his worst tendencies.

When you put Trump in historical context, he’s worse than [former Italian Prime Minister Silvio] Berlusconi. If left to his own devices and unchecked, he would probably deteriorate into the vicinity of Mussolini. But he’s no Hitler. He doesn’t have the cleverness or the patience of Hitler. He would be a great jeopardy to the American project if he did. I don’t accept that ultimate comparison, however.

MJ: Your book does seem to have a bit of an arc to the narrative. We go from the Nazi takeover to the Communist repression, but then to the fall of the Berlin Wall and the rise of political freedom in Eastern Europe. But is this a steady arc? Or is it a bit of a conceit to think of such progress as being inevitable? And where do you put today’s moment on the historical spectrum in this regard?

NE: I would say the book describes what scientists call a sine curve with an upward trajectory. That is: It oscillates. The trend of progress, of democracy, oscillates. You see these cycles. You get a high point after World War I and then it goes down. It drops into a trough of World War II. There’s a flourishing of democracy in the West after World War II, but deterioration again with the Cold War, which really sets in in Prague with the Communist coup in 1948. Then you get an upturn in 1989. Overall, the progress of freedom is steady, but there are significant setbacks. As I was writing this book, what brought this all to life for me was the lives of the people, including my own mother, who rode—like a roller coaster—the ups and downs of these trends.

I’m confident that democracy will triumph again. We do see regimes like Putin’s or those of other illiberals—in Hungary, Poland, Turkey—where freedoms are impaired. But this weakens their regimes and their opponents are empowered by the desire for those freedoms. So I’m confident we’ll get there. The only question ever with democracy—because the overall trend has been positive with these dips for the past three centuries—the only question is how long will it take. And that depends on people acting. I hope readers will close the book at the end of chapter sixteen and think, “Boy, I better vote in the midterms.” The power is in our hands to make this a short interregnum of illiberal reaction led by Trump. In any event, there will be a spring. We want to bring about that spring as quickly as we can.

MJ: Let me be a bit of a pessimist and say: Looking at Europe, which is where the book and the stories take place, we recently had a tremendous flowering of democracy, but now we see in some of the countries you’ve named—Poland and Hungary and elsewhere—a move toward autocratic tribalism, racism, and prejudice in response to pressures that arise from globalization, wars, cultural diversification, and refugee crises. What’s to keep us from saying, “Oy, here we go again”?

NE: We should say, “Here we go again.” The signs are familiar. We should expect that counterattacks on democracy are going to last as long as there is democracy. Part of that “oy” is being ready for the attacks. But I’m encouraged looking in the United States at the ferocity of the pushback. And if you look closely at Europe, you do see a lot of signs of resistance to the illiberal trends on that side of the pond. In Slovakia, after an investigative journalist was killed, there was a massive uprising in that country that drove Prime Minister Robert Fico out of office. In every presidential election in France, the Le Pens—first the father, now the daughter—are a threat. But they’re beaten every single time.

What I write about over the past 100 years we are seeing unfold in slow motion in the United States. But I am not hopeless, far from it. The fight over Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh is going to be a skirmish, a battle to defend our democracy. (It’s too generous to call Kavanaugh’s views illiberal; they’re medieval. His views of absolute presidential power—immunity from criminal prosecution or any intrusion—are far outside the pale.) With the Robert Mueller investigation, we’ve been winning those battles! Mueller is still there. His boss, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, is still there. Mueller has racked up now almost 190 charges, five guilty pleas, a major trial conviction. The big moment will be the midterms. I fear it will be a long winter of democracy if the forces of accountability are not successful.

So I’m optimistic, and it was a treat to be able to tell these wonderful stories. If you meet the characters in this book, they will give you optimism. Even my German general, who at the end of the war turned on the SS and reached out to Gen. George Patton to try to arrange the safe surrender of Prague. He protected Prague and this wonderful palace from destruction. Having spent the past four years with these characters and their century, I think we’ll be okay, as long as we fight for democracy.