Gabriella Cazares-Kelly at the high school where she teaches on the Tohono OíOdham Nation in southern Arizona.Mark Peterman

Gabriella Cazares-Kelly is obsessed with voting. A Democratic Party precinct committee member for her Tucson, Arizona, neighborhood, she keeps a block-walking app on her phone and the Pima County Recorder’s Office on speed dial. When she turned 36 this spring, Cazares-Kelly passed around a petition for a statewide ballot initiative for education funding and told friends and family not to show up to her party if they weren’t registered to vote. She was joking. Sort of.

“Anyone who’s friends with Gabby is already registered to vote,” her friend Rebecca Cohen says.

So not long after the 2016 election, when the executive office of the Tohono O’odham Nation, where Cazares-Kelly is a high school teacher, stopped funding the voter education program she’d been part of, she, Cohen, and a small group of allies filled the void. They formed Indivisible Tohono, inspired by the national resistance organization, and made plans to jump-start small-d democracy among the roughly 13,000 tribal residents on the Connecticut-size reservation. Meeting once or twice a month in members’ homes or at gas stations, they’ve led workshops to train voter registrars, held candidate forums, and recruited members to fill local offices.

“We discovered that there are 24 vacant precinct committee-people spots and not a single one was filled,” Cazares-Kelly told me. “Not only did we not have a seat at the table; we didn’t know what tables we were not being invited to.”

Voter engagement across Arizona’s Indian Country is substantially lower than state and national averages, in part because voting is harder in almost every way. Transportation and mail service are limited. Polling places are scarce. Recent Republican crackdowns on voting rights have compounded the problem. “You recognize the state doesn’t give a shit. You recognize the county doesn’t give a shit,” says April Ignacio, an Indivisible Tohono member. “Well, guess what? The voters don’t give a shit.” In 2016, only about a third of adults on the Tohono O’odham reservation were registered to vote on Election Day—worse than the already low figures for tribal lands across the state. This year, with Arizona on the precipice of becoming a swing state, Democratic groups have spent big bucks to boost turnout. On paper, Native American voters make up a small but essential part of any winning coalition. In the state’s 1st Congressional District, where indigenous residents form a quarter of the population, they helped put Democratic candidates over the top in three of the last four elections. Statewide, there are about 55,000 eligible but unregistered voters living in tribal zip codes—about half the margin of victory for President Donald Trump in 2016. But when it comes to Native voters, says Travis Lane, who runs the voter education initiative at the Inter Tribal Council of Arizona, “we just don’t have the bodies to do this work.” There is no Mi Familia Vota (the preeminent Hispanic voter mobilization group) or NextGen America (which is focused on college students) staking out rodeos with armies of paid, clipboard-toting canvassers. Instead, it’s people like Cazares-Kelly and Ignacio, giving up their weeknights and holding banana bread bake-offs and bingo nights to cover the cost of travel.

The apathy of some tribal members is partly a reflection of history. It wasn’t until 1924 that all Native Americans gained citizenship, 1948 that they could vote in Arizona, and 1972 that the state abolished literacy tests. In 1975, the Voting Rights Act was amended to mandate that translators be made available to assist indigenous voters; another 14 years passed before two of the Arizona counties with the largest Native American populations finally hired indigenous people to do that work. In 2003, the speaker of the state House suggested tribal members were ineligible to serve on state commissions. Retirees in Sun City know they’re voting for a government that’s responsive to what they want. In Indian Country, that’s rarely been the case.

And that, to people like Cazares-Kelly, is part of what makes their work both so difficult and so urgent. Because what happens in Washington, DC, or Phoenix affects them intimately. The Tohono O’odham Nation straddles the Mexican border for 62 miles. Driving around Sells, the tribal nation’s capital, I passed six Border Patrol vehicles in just a few minutes. “Everybody has a story,” Cazares-Kelly says of abuses by Border Patrol. In June, Indivisible Tohono tweeted out a cellphone video of a tribal member being struck by a Border Patrol vehicle; the agent kept driving.

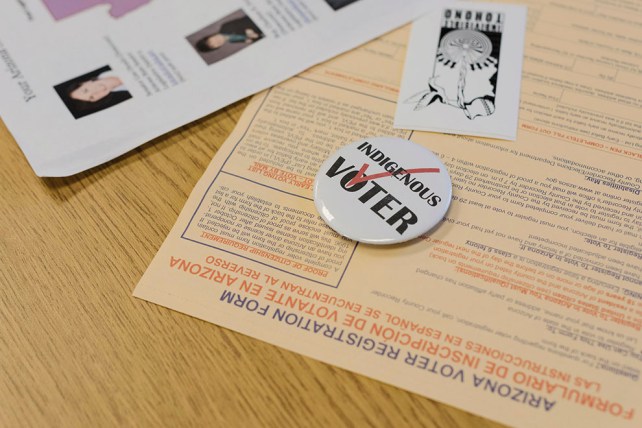

Indivisible Tohono has nine core members, all but two of whom are tribal members. I dropped by one of their meetings in early August, held at a Shell station in Sells. As they plotted and joked among themselves, intermittently stealing each other’s french fries, they offered a crash course on the obstacles they faced. Other than periodic registration drives—such as one the group held at an August kickball tournament—there is no physical place to sign up to vote on the reservation. Then there’s the paperwork. Tohono residents don’t have street addresses, so the form includes a small box where you can draw a map of where you live. The county recorder then pores over a giant map to find it based on your drawing. Putting down a P.O. box opens up another set of problems, because many tribal members share P.O. boxes—setting off voter fraud alarms—or because the P.O. box is in a different county than their homes.

Counties with large tribal areas often hire Native voter outreach coordinators to handle such questions. But in Pima, the state’s second most populous county, the Tohono coordinator position has been vacant since 2015. Often, when reservation voters call, “they refer questions to Gabby,” Ignacio says.

The local Democratic Party hasn’t always been responsive either. Cazares-Kelly recalled what a party representative once told her when she asked about voter registration efforts: “‘I didn’t know that you needed to do voter outreach on your reservation—I thought people had to register to vote when they applied for food stamps.’” She paused a beat to let it sink in. “That’s problematic in so many ways!”

Meanwhile, some state lawmakers are actively making things worse. The state’s voter ID law, passed by referendum in 2004, included tribal ID as an acceptable alternative to a driver’s license. But it created confusion among poll workers, who in some cases turned away eligible voters whose tribal IDs didn’t completely match their voter registration forms. In 2016, the state passed a new law making it illegal to transport someone else’s ballot. Ostensibly designed to crack down on voter fraud, it meant that voting in places like Sells—where residents routinely pick up and drop off mail for each other—would become a lot more cumbersome. Under the new law, residents who mail a friend’s completed ballot at the post office could face felony charges. (There are exceptions for relatives, household members, and caregivers.) In the 2016 election, the law had a chilling effect. “We had testimony that voting organizers were terrified to even assist anybody filling out their ballot,” says Jacqueline De León, an attorney at the Native American Rights Foundation. Stories of disenfranchisement abound. (The effects of voter ID are more pronounced in North Dakota, where the state’s law was just upheld by the Supreme Court; the North Dakota law requires voters to have an ID with a residential street address—something that’s missing on tribal ID cards.)

The victories Native voters have won in court and in the Legislature are contingent on a government that cares. The expansion of Native voting rights was made possible by the Voting Rights Act and a Justice Department willing to enforce it. The current Navajo County recorder—the first Native woman ever to hold the post—got her start in government thanks to a 1989 consent decree that forced the county to hire a Navajo-speaking voter outreach staffer. But in the half-decade since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelby County v. Holder struck down portions of the Voting Rights Act, 212 polling locations have closed in Arizona. And conservatives are pushing for more voting rights rollbacks. The Republican nominee for secretary of state, Steve Gaynor, has advocated the elimination of ballot translations entirely.

It may never be as easy to vote in Sells as it is in Sun City. But that’s not the point. For now, organizers like Cazares-Kelly just want tribal members to feel heard. Indivisible Tohono’s breakthrough came this summer, when 19 candidates for state and local offices—including David Garcia, the eventual Democratic nominee for governor—dropped by Sells for the first-ever candidate forum on the Tohono O’odham Nation. Attendees ate tamales, and candidates received seashell necklaces. Indivisible Tohono members worked at a table with voter registration forms.

“I’m sick of the scraps,” Cazares-Kelly says. “We’re sick of the scraps. We’re trying to bring about positive community change, and we’re gonna keep showing up.”