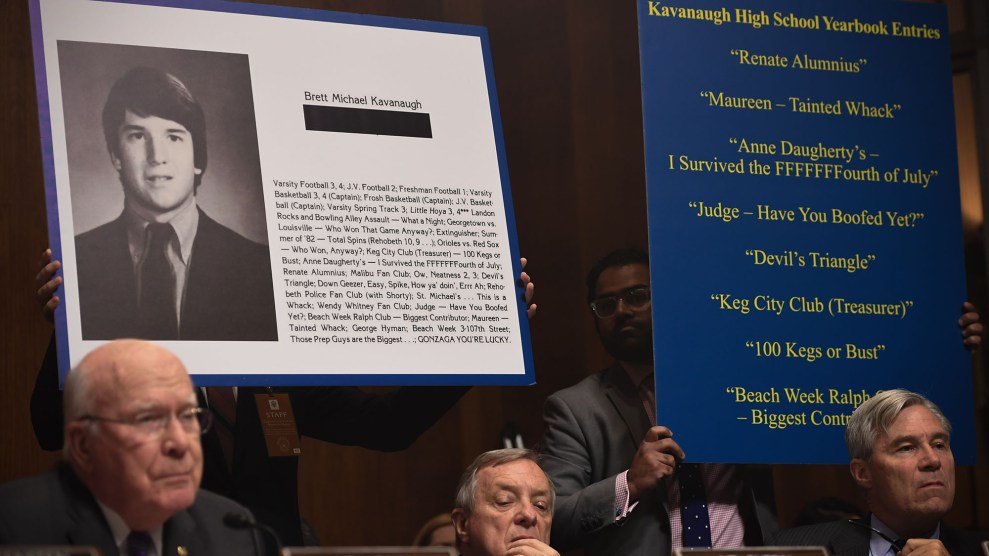

Excerpts of Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh's high school yearbook are displayed as Kavanaugh testifies before the US Senate Judiciary Committee on September 27.Saul Loeb/ZUMA

When Brett Kavanaugh was nominated to the Supreme Court in July, his high school social network had his back. Within 24 hours, more than 100 alumni of Georgetown Prep, the elite Jesuit high school outside Washington, DC, that Kavanaugh attended from 1979 to 1983, had signed a letter urging the Senate Judiciary Committee to confirm him.

“The network itself starts when you’re in school,” Paul Murray, a classmate of Kavanaugh’s who organized the letter, explained the next day to WAMU, the Washington-area NPR affiliate. “It’s a close-knit school. We are tight classes. Friendships lead to business, and so you have a lot of people that have been successful.” Murray added, “Most people, if they had 150 of their high school friends when they’re 53 years old stand behind you, I think that says a lot.”

Murray’s comments were clearly meant as praise to both Kavanaugh and the school they attended. But in light of the sexual assault claims now leveled against the Supreme Court nominee, they expose a dark reality of the elite prep-school world in which boys depend on each other to advance socially and economically and protect each other’s reputations. It helps explain why several women who went to sister schools in the 1980s have come forward to describe the rape culture that pervaded the prep-school scene in the Washington area, but exceedingly few men have gone on the record with similar recollections. It also helps explain why Kavanaugh’s Yale classmates have been willing to speak to the press (and presumably the FBI) when they believed Kavanaugh was whitewashing his past as a hard partier in college, while very few of his high school classmates have stepped forward to describe Kavanaugh as anything but a Boy Scout who had the occasional beer, the same image he presented to the public and the Senate.

“I think we can legitimately ask why more men aren’t coming forward, especially on behalf of the women they knew,” says Alexandra Lescaze, a 1988 graduate of the all-girls National Cathedral School in a wealthy neighborhood of Washington, DC. “I think that many men are afraid. I think they are all considering their past actions and wondering whether they ever could be accused of something. I think they want to stay on the down low and not put themselves out there.”

After Julie Swetnick accused Kavanaugh of hanging around boys who spiked punch at parties and gang raped inebriated girls, some of his classmates and alumni of other local high schools sent a second letter to the Judiciary Committee calling her accusations nonsense. “We never witnessed any behavior that even approaches what is described in this allegation,” they wrote.

Swetnick’s allegations remain unconfirmed, but it’s unlikely none of those signatories saw behavior similar to what she described. Two days before Swetnick’s allegations were made public, Lescaze, now the executive director of the Hillman Foundation and a documentary filmmaker, recalled similar behavior in an article in Slate:

I distinctly remember being at a Beach Week party with my then-boyfriend when it dawned on us that there was a drunk girl in a room down the hall, and boys were “lining up” to go in there and, presumably, have their way with her. We didn’t know for sure, but my boyfriend and my friend’s boyfriend went to interrupt it and sent her on her way down the stairs. All I remember about her is that she was in the class above us and had dark hair. My friend has told me she remembers boys saying, “I’m next,” which was why our boyfriends went to stop it. That was the only time I can clearly remember a situation that was so obviously a “lineup,” as it was referred to by some at school. My friend remembers witnessing another, and though there weren’t lineups of this nature at every party, they happened often enough that we had a term. We didn’t call it rape.

It was not always so formal a queue. I remember another time when boys were sitting in kind of a campfire circle that could have started as a game of spin the bottle. But by the time I walked through the room there was a girl who was drunk and in the center of the circle, and the boys were taking turns putting their hands up her skirt instead of kissing her.

Women who endured this 1980s prep-school scene recall a specific power structure to explain how the boys got away with aggressive sexual behavior and why the women stayed silent about it. Today, the women are increasingly coming forward to share their memories, including personal stories of assault. “I can’t even tell you how many people I’ve heard from,” says Lescaze of the notes she received following her Slate article. “It makes me shaky. I just can’t believe how many people have been holding this for so long. It’s just like another collective #MeToo scream that’s happening in unison here.” She’s heard from a few men as well, she says, but far fewer. “They know these things happened,” she says, “but we are not seeing enough men stand up and speak.”

Meanwhile, Kavanaugh’s high school friends are sticking with him. A few have defended him publicly, though most have remained out of the press. One spoke anonymously to the New Yorker, after the FBI declined to interview him, and described Kavanaugh as a member of group that preyed on Georgetown Prep classmates and girls at other schools. The paucity of male voices from the prep-school world is “a key indicator of the culture of secrecy and the code of what it means to go to that prep school,” says Deirdre Bowen, a law professor at Seattle University School of Law who attended Georgetown Prep’s sister school, Academy of the Holy Cross, while Kavanaugh was at Georgetown Prep.* “You count on everybody to keep your secrets, and you also know that if you were not to keep someone’s secrets, there’s retribution.”

Bowen didn’t know Kavanaugh in high school, but she knew some of his friends, and she knew the culture of their elite world. (Bowen did note there were a number of students receiving financial aid who did not have an upper-class background.) The boys would band together, promote each other, and protect each other. “In the 1980s, males all knew that they were going to go to college and that the doors were open for them in a predictable future,” she recalls. “Who you knew and what your reputation was was the most crucial part.” The crew that Kavanaugh was part of, a group that included jocks, knew their futures were guaranteed if they stuck together. The more they showed off their masculinity to each other, she says, the closer the group was—and the more need for secrecy about what went on.

For women, there was an entirely different reason to stay silent about the culture of assault: Their reputations would depend on not falling prey to the boys. “Our concern was not about engaging in bad behavior and making sure that everybody kept our secret,” Bowen says. “It was protecting ourselves and our reputation because those secrets wouldn’t be kept by the boys. They would be made fun of by the boys, or information would be spread about us as to who is easy access and who is not.”

One example is the well-known Renate Alumnius entries by multiple boys in Georgetown Prep’s 1983 yearbook, including Kavanaugh, who appeared to be bragging about their alleged sexual exploits with a girl they sometimes mocked as easy. Girls who were assaulted were also objects of scorn. “The girls that this did happen to were called sluts, absolutely,” says Lescaze, referring to victims of rape and abuse. “And they made up nicknames for them that sort of everybody knew. And they were not nice nicknames. And often, those are the ones that those boys put in their yearbook pages.” She recalls one nickname in particular that made reference to a girl’s genitals.

At the time, the Catholic Church was covering up its own rampant abuse. “Their priority was protect and hide, not care for the victim,” Bowen says. She believes this message filtered down to students at Georgetown Prep, which was run by priests. The school would host football games and pep rallies and invite people like Bowen from sister schools. On the morning of such an event, she recalled, senior boys would make an announcement—she believes it was over the intercom—that girls were coming over “and they will be available.” “I mean, just loaded with a clear sexual innuendo,” she says. “That was permitted by the priests who ran the school.” A Georgetown Prep alum recently recalled the same announcement, anonymously, to the Washington Post: “After the [football] game, there will be a mixer. Girls from Holy Cross, Holy Child, and Visitation…will…be…available.”

If any of the priests abused Georgetown Prep students when Kavanaugh was in high school, it’s not public. But in 2003, a student named Eric Ruyak alleged that he had been molested by one of the priests, Garrett Orr. Orr later pleaded guilty to two instances of abuse, the first in 1989. When Ruyak came forward, he told the Washington Post Kavanaugh’s close high school friend, Mark Judge, came after him. “Numerous alumni told me that Judge was going around saying I was emotionally unstable and a sexual deviant,” Ruyak told the Post.

“The connection I see is just that whenever you have this entrenched power, the community protects itself,” says Lescaze, whose own high school and brother school, St. Albans, were affiliated with the Episcopal Church. “And I think that’s what was happening in this case, too.”

Both women stress that not every boy at the Washington-area prep schools was disrespectful or predatory. Rather, it was a smaller group that engaged in this behavior. But after her sophomore year in high school, Lescaze and her girl friends stopped hanging out with boys from the local all-boys school and instead made friends with kids at co-ed public schools, where they “met totally different kinds of guys, and it was great,” she says.

As for Kavanaugh and his clique at Georgetown Prep, it’s unclear how much about their high school experience they divulged to the FBI in a hurried investigation in which, according to the White House, just nine people were interviewed. It’s also unclear how many of Kavanaugh’s classmates were among those nine, and how forthcoming they were. Under oath, Kavanaugh downplayed the drinking culture at Georgetown Prep and misled senators about it, sending a clear signal to his old classmates that they could do the same.

When they all gather at the end of the month for their 35th high school reunion, Kavanaugh may by then be on the Supreme Court, saved by the network that rushed to support him in the first place. They will have proved true what Kavanaugh himself said back in 2015: “What happens at Georgetown Prep stays at Georgetown Prep.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated Bowen’s student tenure at Academy of the Holy Cross. She did not graduate from the school, because she moved away before her senior year.