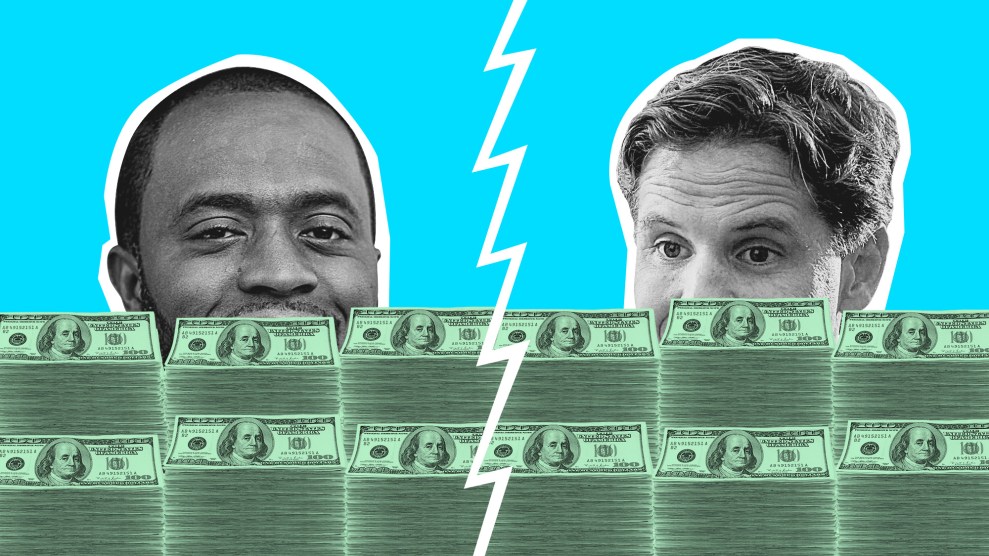

Mother Jones illustration

Tony Thurmond and Marshall Tuck are both Democrats, they agree on most policy issues, and the office they’re battling for has little, if any, enforceable power. Even so, more than $40 million has flowed into their race to be California’s next school superintendent in November—making it the most expensive superintendent race in history.

The superintendent of public instruction, which is nonpartisan, doesn’t set the education budget—the governor does—nor do they hold power over policymaking—the state Legislature does that. The superintendent’s main role is rather to engage with local school districts and, for the most part, implement the policies set by the governor-appointed members of the State Board of Education.

That said, the person in the role can be a powerful messenger. And in California, it’s a job that’s caught up in a long-running battle over the shape of a vast education system, which has reflected larger fault lines in education reform across the country. This race for school superintendent has essentially evolved into a proxy war between two incredibly powerful factions: the influential and well-organized behemoths, particularly labor unions, focused on investing in traditional public schools, and deep-pocketed players who argue privately run, publicly funded alternatives like charter schools should have a significant role in the education system. And each side’s spending suggests they’re hellbent on controlling that soft power.

“There’s a consequential battle between two competing visions of the future of the education system,” says David Plank, a professor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education. “The superintendent is the public face and public spokesperson for California’s school system. It’s very important to the unions that the person in that office articulates a vision of California public education that is consistent with theirs.”

The battle over school choice in California goes as far back as the early 1990s, when the state became the second in the country to allow charter schools. California now has the most charter schools in the country—about 630,000 of the state’s 6 million students are attending charters this year, with large concentrations in Los Angeles and San Diego. And as the presence of charter schools grew in the state, so did that of their supporters—largely a collection of wealthy philanthropists and billionaires, from members of Walmart’s Walton family to tech investors, who call for innovation as traditional public schools struggle to serve students, particularly poor and minority students. So did their opponents, mainly teachers unions, who viewed the promotion of charters as a threat to traditional public schools and to teachers themselves.

The debate, of course, has long played out in the state’s politics. In 2000, the powerful teachers union helped defeat a ballot measure by venture capitalist Timothy Draper to start a voucher program, and in the past few elections, prominent education reform supporters have poured millions into pro-charter groups to support state legislative candidates. This debate became so pointed that last year’s Los Angeles Board of Education race turned into the most expensive school board race in US history (charter school advocates netted a majority of the seats). But the past two governor’s elections have proved largely uncompetitive, so outside spending from the pro- and anti-charter camps appears to have settled further down the ballot, on the superintendent’s race. (For instance, in the June primary this year, education reformers were hoping they’d be able to more directly influence Sacramento, and heavily supported charter school proponent and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa; he came in third place with 13 percent of the vote.) Tuck previously ran for superintendent in 2014, losing to the current officeholder, Tom Torlakson, who is term-limited; that year, at least $30 million was spent on the race, making it the most expensive superintendent race in California history at that point.

Now, the matchup between Tuck, who led in the June primary by less than two points, and Thurmond is just the latest—and more expensive—flashpoint.

While Thurmond and Tuck agree on most big-picture education issues—they both support more school funding, free universal preschool, more transparency and oversight for charters, solutions to the state’s teacher shortage, and a recently approved ban on for-profit charter schools—the key sticking point is what specifically to do about charter school growth.

Thurmond, for his part, believes the state needs to consider a “pause” on the approval of new charter schools to assess how they hurt the rest of the district’s funding, and he argues that the state is already failing to hold all schools to the same accountability standards. The position echoes that of the California Teachers Association, which, along with the California Democratic Party and current superintendent Torlakson, support Thurmond, a former social worker and school board member turned assemblyman representing Richmond, California. While Thurmond broadly supports charters, he points to Oakland Unified School District as an example of the problems that can arise: The district has more charters per capita than the rest of the state and, according to a University of Oregon study, lost $57 million last year following declining enrollment.

“I think we should have charters have the same accountability as public schools,” Thurmond tells Mother Jones. “The idea of a pause is simply to say, ‘Let’s be thoughtful about a growth plan and what’s sustainable and what’s not.’ Right now, it’s like anything goes. You have a board that meets in Sacramento making decisions about a charter school managed by a school district in Los Angeles or the Central Valley.”

On the other side, Tuck, who once worked in finance and later oversaw a Los Angeles-based charter school network and a group of district schools through the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, is considered more charter-friendly and has earned the support of the California Charter Schools Association, former Obama Education Secretary Arne Duncan, and the Association of California School Administrators. Like Thurmond, he believes charters should be held accountable, and vows that, if elected, his office would be “much more proactive about shutting down bad charter schools.” But, he argues, a moratorium on opening new ones is not a solution; rather, the key is to allow districts more flexibility to innovate and improve—in good schools, charter or otherwise.

“The job of the state is to provide a quality public school for every child in every neighborhood. We’re just not getting that job done today,” Tuck told Mother Jones. “So the idea of having another public school option to help deliver on that promise, I think, is helpful, knowing that you must have certain policies to ensure there are not unintended consequences.”

“We both believe that kids deserve better,” he adds. “My opponent is more aligned with the current direction of public schools. California needs a real turnaround.”

Tuck has attracted big money for this positioning. Committees supporting his campaign have spent more than $32 million, more than twice what groups endorsing Thurmond have hauled in. And if you consider just direct campaign contributions, Tuck’s campaign has brought in $5 million, while Thurmond’s campaign has received just over $3 million from such donations.

More than $21 million in outside spending to groups supporting Tuck came from EdVoice for the Kids PAC, according to Rob Pyers, research director at California Target Book. State campaign finance records show the committee has received $5.2 million from high-profile, pro-charter billionaires like Eli Broad, the Walton family, and Netflix CEO Reed Hastings since January. (Both Broad and the Waltons have long been involved in charters: Broad’s foundation backed a $490 million plan to put half of Los Angeles students in charter schools by 2023, while members of the Walton family have given millions of dollars to support charter growth throughout the country, including investments in the California Charter Schools Association.)

Meanwhile, a committee supporting Thurmond has raised over $12 million, more than $8 million of which is from the California Teachers Association.

All that money has inevitably led to an increasingly contentious campaign, with mudslinging on the airwaves from both sides in recent weeks. The education news site EdSource reported that committees supporting Tuck have spent $8.1 million toward TV ads, nearly twice the $4.4 million spent by a committee supporting Thurmond, as of September 22. Both candidates disputed to Mother Jones the claims their opponent is making in their ads.

In the ads, Tuck is framed as a Wall Street banker supported by charter-backed billionaires and allies of President Donald Trump and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Tuck calls the ad “unfortunate,” and states he has a “long track record about being against this administration from before day one” and has not been endorsed by DeVos, as the ad implies. (That said, members of the Walton family have given to PACs supporting Tuck, as well as one once led by DeVos.)

“My opponent is telling lies he knows [are] false and then running for the position of superintendent, which is supposed to be a role model for kids,” Tuck says. “That’s a problem.”

Thurmond, on the other side, is criticized as a politician who had a problematic tenure while on the West Contra Costa Unified School District board, of which he was a member from 2008 to 2012. An ad from his opponent’s supporters states the district was “sued for leaving at-risk students in rotting trailers with mushrooms growing in the floors” and “reprimanded by the Obama administration for failing to address widespread sexual harassment and assault in district schools.” In reality, Thurmond was not directly reprimanded by the Obama White House, though he was named in a lawsuit against the district, as was the rest of the board.

“These campaign ads are all about mischaracterization for a political purpose. They are spreading lies,” Thurmond says. “This job is about helping kids. I don’t think it’s appropriate for a candidate. In their attempts to denigrate me, they are denigrating those kids who are at that district that is trying to get better. I’m proud of going to a district that was in trouble.”

Still, in the face of all this money, the question remains of just what the superintendent can actually do. The state superintendent’s limited power ultimately comes down to being an effective and visible messenger, who works with lawmakers and the governor to pursue policies they support. If the superintendent wants to propose legislation on, say, universal preschool, they are in the position to work with lawmakers to advance the legislation.

As Kevin Gordon, president of Capitol Advisors, a Sacramento-based education consulting firm that works with public school districts throughout California, puts it, neither side of the charter debate “wants a state superintendent that commands a bully pit for messaging that supports the other side.” It gives a “major megaphone” to the officeholder, according to former superintendent Jack O’Connell, who says he was able to use the position to “influence public opinion.”

“You don’t sign bills into law. You don’t vote on legislation. You have to be judicious in injecting your influence,” O’Connell says. “You set the tone for education. You establish and set the culture of high expectations for all of our kids.”

Delaine Eastin, who served as California’s superintendent for eight years before O’Connell, echoed her successor, arguing that the superintendent can pressure the state Legislature to invest more in schools and “make recommendations to the state board that more charters can be granted if the districts and counties turn them down.”

“The hope is that if Tony Thurmond gets in, there would be more requirements that charters are playing by the rules,” Eastin says. “The hope on the other side is if Marshall Tuck gets elected, his supporters want a lot more charter schools and want to break what they see as the power of the unions, especially the California Teachers Association. The reality is that there’s no quick and dirty solution to improving schools. The real role of the next superintendent is to get more resources into the system or it’s going to be underinvested [in].”

Despite the heated debate over the particulars of charter growth, the candidates are in close agreement on the money issue. They both seem disheartened, and take pains to say they’d remain independent from their big donors. Tuck says he wishes the money was spread out across state races, but that the lack of debate over education as an issue in the governor’s race has opened the door for spending on this race. “Having a lot of money focused on communicating people’s positions on how to improve our public schools, I think that’s very important,” he says. “We have a crisis in our public schools.”

“I wish the money being spent in the race was going into our programs to help kids in the state. That’s where it would be best used,” Thurmond says. “I understand that these public employee groups feel like public education is under the attack. They feel like the mostly billionaire-backed kind of movement is blaming unions for the problems in our schools [and] wants to take away tenure and make it easier to fire teachers.”

He adds, “This whole fight misses the issue. I think we have to be putting more into our students. When we have these big fights and debates, our kids lose.”

Image credits: Andrew Blumenfeld/Wikimedia; LightSlash/Wikimedia; Getty