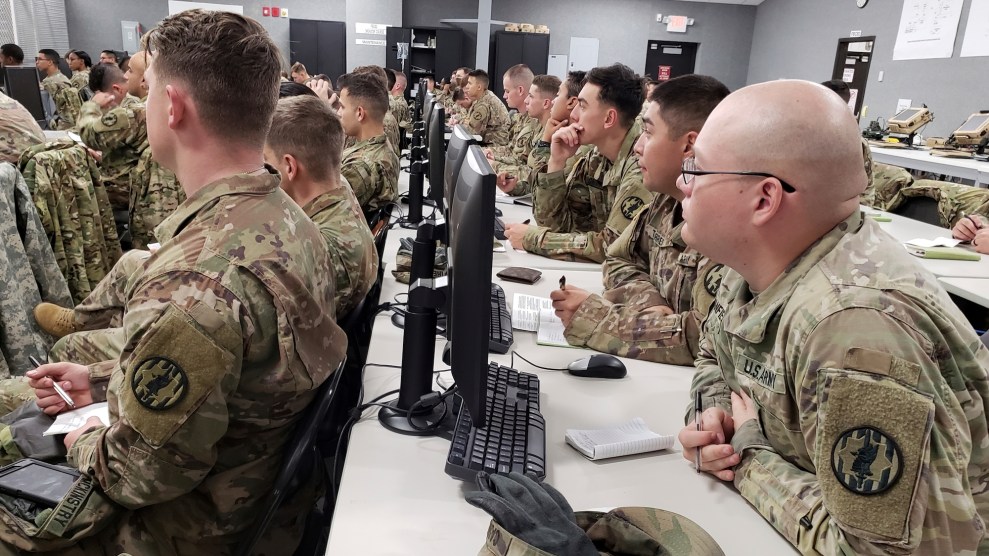

Soldiers receive a legal briefing as they prepare to deploy to the US-Mexico border to support Customs and Border Protection.U.S. Air Force/AP

President Donald Trump likes to portray the still-distant migrant caravan as an invasion: a dehumanized mob that can only be stopped by military might. At Trump’s behest, the Pentagon is now deploying more than 5,000 active-duty soldiers to the border, on top of the 2,100 National Guardsmen who are already there. Trump, who is hellbent on attacking migrants to motivate his base before the midterms, said on Wednesday that he might send up to 15,000 troops to the border, more than the entire US military presence in Afghanistan.

What another 10,000 troops would do is a mystery, even to the commander of US Northern Command, which is responsible for security in North America. “I…saw 14,000 out there,” General Terrence O’Shaughnessy said on Tuesday about rumors of a bigger troop deployment. “I’m not—I honestly don’t even know where that came from. That is not in line with what we’ve been planning.” Soldiers can’t legally enforce immigration laws, so some of the 5,200 troops being deployed now will do things like shoveling manure from the Border Patrol’s horses, in addition to providing logistical support. Like many of the Border Patrol agents they are reinforcing, the soldiers are likely to be extremely bored. The one thing they will almost certainly not be is overwhelmed.

The caravan of roughly 3,000 to 4,000 people walking toward the United States is currently in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca. It has already diminished in size as some individuals and families opt to stay in Mexico, turn back, or head off on their own. If caravan members head to the nearest border crossings in Texas, they still have more than 800 miles to go. If they follow past caravans and go to California, they will need to cover more than 2,000 miles. (Right now, they’re as close to San Diego as San Antonio is to Seattle.)

It is impossible to know exactly when or how many caravan members will reach the United States. Maureen Meyer, the Mexico director for the Washington Office on Latin America, says that caravan members might start arriving in about two weeks to a month, depending on whether they’re able to get transportation. In April, when Trump sent the National Guard to the border to confront another caravan, roughly 400 migrants—about a quarter of the caravan’s peak size—went to the Tijuana-San Diego border crossing. This caravan is likewise shrinking, and will continue to shrink as the trek goes on. By last week, Mexico had already received applications from more than 1,700 caravan members to seek asylum in the country and remain there.

Stephanie Leutert, the director of a Mexico security initiative at a University of Texas at Austin research center, says past caravans have taken the long route to California to avoid Mexican cartels. Those caravans had more centralized leadership, however, and it’s unclear where this caravan is headed. One thing is apparent, though. “By the time it gets to the US,” Leutert says, “I don’t think it’s going to look the way that it looks at all right now.”

Once at the border, some migrants—particularly adults without asylum claims—are expected to try to cross the border illegally. That is not unusual: Border Patrol apprehended about 1,400 people a day in September. (That number is itself low by historical standards; in the 1990s, there were about 3,500 apprehensions a day.) Family members and minors traveling alone will be much more likely to ask for asylum at officials ports of entry or by presenting themselves to Border Patrol agents after crossing into the United States.

Those who request asylum at border crossings—which is what the Trump administration has told them to do—are likely to be confronted with weeks-long waits. Joanna Williams, the education and advocacy director at the Kino Border Initiative, told Mother Jones earlier this month that there are now about 20-day waits at the Arizona border. Leutert says migrants in Tijuana are waiting a month. Meyer says that if the Trump administration were crafting a logical response to the caravan, it would increase capacity to process asylum claims at ports of entry. But it does not appear to be doing so.

The long waits at ports of entry will likely persuade some asylum-seekers to cross the border illegally so that they can be detained by Border Patrol Agents and request protection. As Mother Jones reported in August, those who opt to wait to be let in could risk being detained by Mexican immigration officials as part of what appears to be a coordinated effort with the United States to prevent some people from requesting asylum in the United States.

To understand the boredom awaiting US troops, it helps to look at the numbers. In a typical month in 2018, the Border Patrol apprehended only two migrants per agent, about one-tenth of the number in the early 1990s. “I understand guys have a tough time staying awake,” one Border Patrol supervisor conceded in 2011. Agents who brought pillows to work were known as “felony sleepers.” Now, Border Patrol is apprehending more families, but that’s not exactly hard work, since many of them want to be caught. A senior Trump administration official told reporters the week before the initial troop announcement that the problem at the border is not that people are getting into the United States, but that they aren’t being deported after they’re apprehended.

In fiscal 2018, the average Border Patrol agent apprehended 23 migrants. All year.

9 of them would've been kids and family members, leaving 14 single adults, all year. One per agent, every 26 days.

And now, at great expense, 5,200 active-duty soldiers are headed to the border. pic.twitter.com/6KcFyT32Fc

— Adam Isacson (@adam_wola) October 30, 2018

After Trump deployed the National Guard to meet the April caravan, Brandon Judd, the head of the Border Patrol union and a vocal Trump supporter, called it “a colossal waste of resources” and said, “We have seen no benefit.” General O’Shaughnessy said on Tuesday that the cost of the deployment is “unknown at this time.” The Bush administration spent $1.2 billion to send 6,000 National Guardsmen to the border between 2006 and 2008, although sending active-duty soldiers could be a bit cheaper. Adam Isacson, the defense oversight director at the Washington Office on Latin America, estimates that the deployment of 5,200 troops will cost about $1.75 million a day. An unnamed Pentagon unofficial estimated to Newsweek that the total cost would be at least $50 million.

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis defended the decision to deploy active-duty troops on Wednesday, saying, “We don’t do stunts in this department.” A few hours later, Trump said he might send 10,000 to 15,000 troops. If that happened, there would be roughly 32,000 US soldiers and Border Patrol agents along the border, or about 16 per mile. The Pentagon has notified 7,000 active-duty troops that they could be deployed to the border in addition to the 5,200 soldiers set to arrive by this weekend.

Meyer believes it will become clear that caravan members are not a threat to US security once they begin to reach the border. “These are not large numbers of people seeking to somehow invade the country,” she says, “but a manageable number of people that the US has proven that it’s able to address pretty much every day at the US-Mexico border.”