The El Barretal camp in Tijuana, Mexico, where many migrants are now living.Noah Lanard/Mother Jones

In April, after Nicaragua’s increasingly authoritarian government began killing protesters, Isaac Molina tried to help. Molina saw the carnage at a university in Managua and rushed home to fill a backpack with medicine and other supplies. The government quickly closed hospitals and told doctors not to treat injured protesters. Molina, a 26-year-old doctor, kept treating them.

He was threatened for the first time in May after being identified as a member of a volunteer medical brigade. One month later, he said the police pulled him over and shot him twice, in the abdomen and the back. He fled with his wife and two young children in August and arrived at the US border in Tijuana in November. Shortly after arriving, he turned around and traveled to the other side of Mexico to wait.

Asylum-seekers used to be able to simply walk across the border and make their claim for protection—a right enshrined in US and international law. That is no longer the case. Under a policy that began in 2016 and grew far stricter last year, asylum-seekers in Tijuana and all along the border must now wait for weeks to be allowed into the United States to request protection.

The US government is now in the third week of a shutdown over President Donald Trump’s insistence on $5 billion to build part of a border wall. But the problems on the ground in places like Tijuana have nothing to do with physical security and everything to do with a Trump administration policy aimed at deterring people from seeking asylum. The result is a huge backlog and a humanitarian crisis for people fleeing persecution who are now forced to wait for weeks or longer in dangerous places along the border.

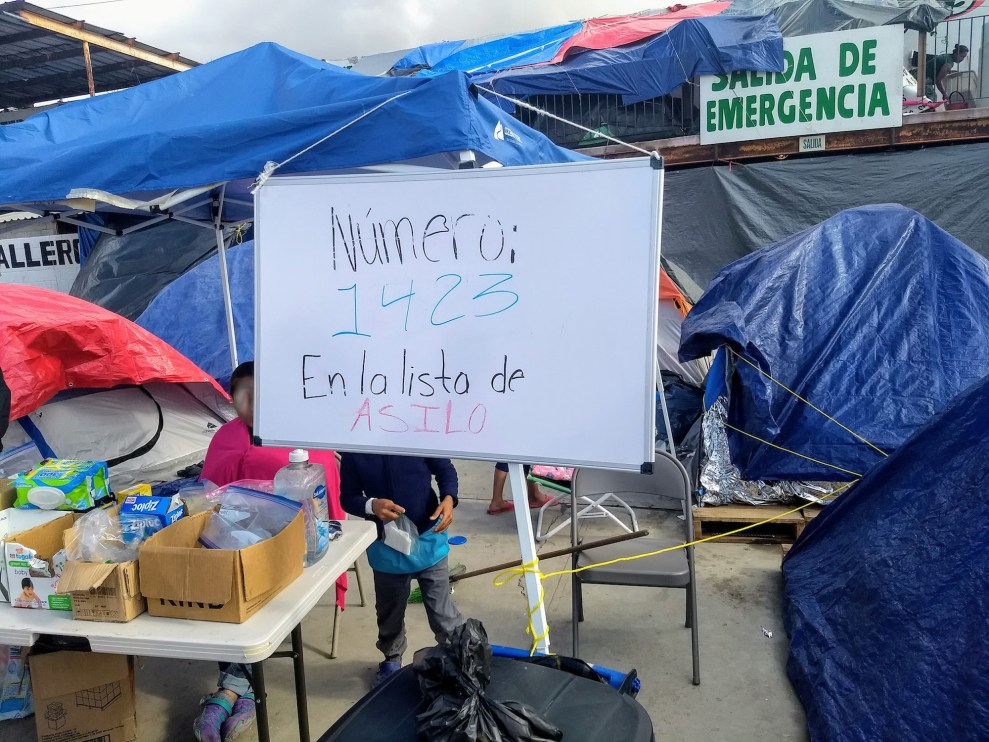

In Tijuana, asylum-seekers must get a number from fellow migrants, who manage a list in coordination with Mexican immigration officials. Each number corresponds with the names of 10 asylum-seekers, handwritten in a notebook. Asylum-seekers cannot get into the United States until their number is called. So every morning, migrants whose numbers are coming up—and many whose aren’t—come to a small plaza and wait for US immigration officials to tell their Mexican counterparts how many people they’re taking in that day.

Just after Christmas, the migrants responsible for the list were shouting the names of asylum-seekers who had registered nearly six weeks before. Molina had spent the past month with his wife and two young children in Veracruz, Mexico, roughly 2,000 miles away. They knew no one there, but he felt it would be less dangerous than waiting in Tijuana, where more than 2,500 people were murdered last year—six times as many as in 2011. Last month, two teenage migrants from Honduras who arrived as part of a migrant caravan were murdered in Tijuana. Molina returned to Tijuana with his family when his number was close to being called.

Molina’s family waits with their bags in Tijuana. Molina asked that their faces not appear in the article.

Noah Lanard/Mother Jones

Asylum-seekers are not supposed to need to be on a list in Mexico to be eligible for protection in the United States. Offloading the initial asylum processing onto the Mexican side of the border has led to a long list of humanitarian concerns. US law clearly protects migrants’ right to seek protection regardless of age, but Mexican immigration officials in Tijuana do not let minors put their names on the list. Instead, they turn them over to Mexican social services workers who may move to deport them to their home countries. Nicole Ramos, an attorney with the Tijuana legal services group Al Otro Lado, says some transgender and African migrants have been unable to put their names on the list after being blocked by list managers.

Migrants are also prevented from registering if they don’t have identification, even though there is no such requirement under US law. In some cases, Ramos says, migrants managing the list have demanded sexual favors or bribes in exchange for preferable treatment. Al Otro Lado and asylum-seekers forced to wait in Mexico are suing the Trump administration to stop the turn-backs by US border officials, but a judge has not yet issued a ruling.

In 2016, after thousands of Haitians arrived in Tijuana, the Obama administration began limiting the number of asylum-seekers allowed to cross the border and moved to impose daily quotas shortly before Trump took office. The policy became much stricter last year, and weekslong waits are now common. Administration officials insist that restricting the number of asylum-seekers allowed into the United States is simply a response to the limited capacity to process migrants. In reality, the Department of Homeland Security appears to have little interest in increasing capacity. Jud Murdock, a senior Customs and Border Protection official, told congressional staffers that CBP is letting in only 100 people per day at San Diego’s San Ysidro crossing because “the more we process, the more will come.” The actual daily average is closer to 50.

In December, California Democratic Reps. Nanette Barragán and Jimmy Gomez accompanied 15 asylum-seekers to the San Diego side of the Otay Mesa port of entry. They were forced to wait and were eventually penned in by metal barricades held together with zip ties. Gomez slept on the concrete as the group waited for all the asylum-seekers to be allowed in, a process that wound up taking nearly 20 hours and attracted significant media attention. As they waited, Barragán and Gomez asked to see the spaces that were allegedly at capacity, but they were not allowed to do so. Ramos compares CBP’s claims about lacking space to arguing with a toddler. “You’re like, ‘You’re lying. I see the chocolate bar in your hand,’” she says. “This is disappointing that this is acceptable behavior for law enforcement. Their job is to enforce the law.”

Hour 11. Been here since 2pm. Still waiting for asylum seekers to be processed and @CBP to show us their capacity issues. We are not leaving the Otay Mesa facility. Guess we’ll be spending the night. pic.twitter.com/bVbmDGxuER

— Rep. Jimmy Gomez (@RepJimmyGomez) December 18, 2018

The wait times are one part of a larger humanitarian crisis that began after more than 5,000 members of the migrant caravans vilified by Trump began arriving in Tijuana in November. Molina, who arrived in Tijuana independently, was lucky to have the means to be able to wait away from the border. Caravan members initially stayed in a sports complex so close to the border wall that a home run from the baseball diamond could land in the United States. In late November, after US border officials tear-gassed migrants trying to cross the border, Mexican officials moved people from the camp and and to an abandoned club known as El Barretal. The open-air venue is a 15-mile trip from the San Ysidro crossing, partly along long stretches of shanties that line the road.

El Barretal, which the shelter’s manager told the New York Times is now home to around 1,000 migrants, is essentially a refugee camp on America’s doorstep. Migrants sleep in camping tents and receive two daily meals cooked by celebrity chef José Andrés’ nonprofit World Central Kitchen. Doctors Without Borders provides medical assistance, a Spanish group called Psychologists Without Borders offers mental health services, and UNICEF Mexico looks after families. There are reports that El Barretal will be shuttered in the coming weeks, but for now it has a feeling of semi-permanence. When I visited in December, migrants were selling everything from loose cigarettes to Honduran street food. Some migrants gathered around a small tent outfitted with an improbable television, while others played cards or listened to an impromptu concert. A whiteboard showed the latest asylum number called so migrants could know roughly when to head to the border crossing.

A whiteboard at El Barretal shows what number will be called first at the San Ysidro border crossing the next morning.

Noah Lanard/Mother Jones

Many migrants are stuck at El Barretal because the United States is forcing them to wait to request asylum. But others are not planning to request protection. A survey of more than 1,000 caravan members in November by El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, a Mexican research institute, found that about a quarter were planning to apply for protection in the United States, although Ramos says many migrants might not have been aware that they could be eligible for asylum. Many intend to stay in Mexico, while others plan to cross the border illegally. Some are still waiting to make a final plan.

In theory, Molina and the other asylum-seekers the United States is slowly admitting could be among the last ones allowed to make their cases from within the United States. In December, Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen announced that Mexico and the United States had reached a deal under which asylum-seekers will be forced to wait in Mexico while their US claims are pending. There is currently a backlog of more than 800,000 cases in US immigration courts, and immigrants often wait two to three years for their cases to be decided. The new plan, known as Remain in Mexico, could force migrants to spend years in dangerous border towns or other parts of Mexico. The plan would likely make it impossible for an even larger share of asylum-seekers to obtain legal aid, since it is much harder to find pro bono US immigration lawyers from abroad. There is no right to counsel in immigration proceedings, despite the fact that asylum cases are often life-or-death matters.

In Tijuana, it was not at all clear if or when the plan might go into effect. One of the Mexican immigration officials who helps oversee the Tijuana asylum list told me he didn’t know anything about when Remain in Mexico might begin. César Anibal Palencia Chávez, Tijuana’s migrant services director, also wasn’t sure when the new policy might be implemented.

When Molina’s name was called on December 27, he appeared to be overcome with emotion and on the verge of tears. His family took a cab to meet him at the plaza, and Andrew Free, a Nashville-based immigration attorney who is working with Al Otro Lado, asked if he and his wife were legally married. Molina told him they weren’t. Free was concerned: It made Molina more likely to be separated from his family while in DHS custody. Free handed Molina’s sons two chocolate bars and told them to eat them before they got to the other side because outside food is not allowed in US detention centers.

Soon after, they walked toward a Mexican immigration van that would take them to US immigration officials on the other side of the border. They carried spotless suitcases and looked like a family headed out on vacation. Instead, they were on the verge of being detained in the United States. More than a week later, Free says Molina still appears to be in CBP custody—his phone goes straight to voicemail, and his name does not appear in a database of detainees transferred to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement—even though people are not supposed to be held by the agency for more than 72 hours. After a month waiting in Mexico to make it to the United States, the waiting game continues.

Molina on his way to the Mexican immigration van that would take would him to the United States

Noah Lanard/Mother Jones