Mother Jones illustration; John Carnemolla/Getty

Mike Madrid has been witnessing the California Republican Party’s slow decline for more than 20 years. A veteran GOP consultant known as an expert on Latino voting trends, Madrid says he’s watched in dismay as his fellow Republicans have failed to keep up with their constituents, who have become more diverse and more progressive. “I was the political director of the party in 1996. I was asked to come on board to change the direction,” he recalls. “Everything I surmised was summarily dismissed. I said, ‘Okay, but what happens is, you’re not going to exist in a couple of decades.’ And here we are.”

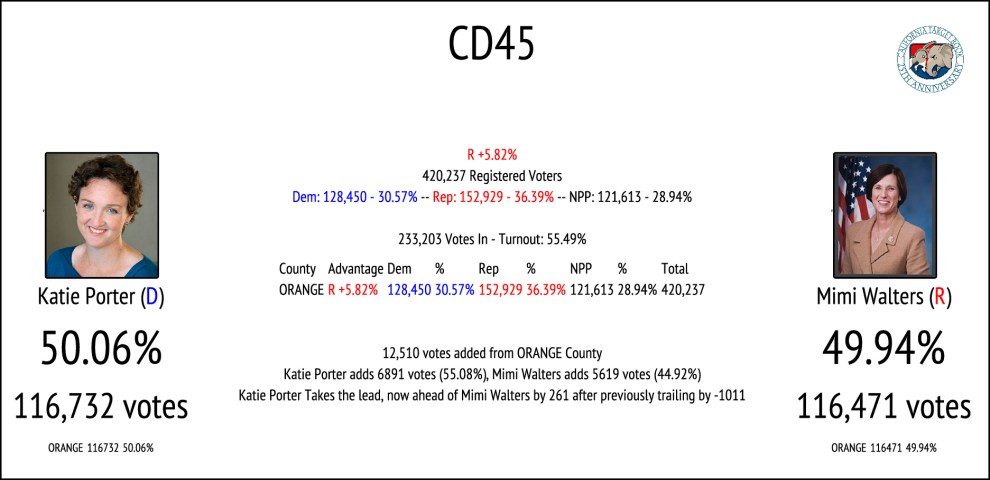

A pummeling at the polls in November was the latest sign that the state party may have entered, as state Assemblyman Chad Mayes of Yucca Valley puts it, a “death spiral.” Republicans lost every House seat in Orange County, a historical bastion of conservatism. They now hold just seven House seats—their lowest number since 1944. They lost every race for statewide office. Meanwhile, the Democrats picked up three state Senate seats to command 29 of the 40 seats and boosted their majority in the state Assembly to 60 out of 80.

And the damage didn’t end in November: Last week, Assemblyman Brian Maienschein of San Diego quit the GOP to join the Democrats. “Donald Trump has led the Republican Party to the extreme on issues that divide our country,” he said, noting that as the party moved further to the right, his values moved to the left. Republican Assembly Leader Marie Waldron called him a “turncoat.”

Maienschein’s defection gets to the heart of California Republicans’ quandary: If they are to survive in a solidly blue state, should they embrace or reject President Donald Trump and the national Republican brand? While Trump enjoys high ratings among California Republicans, he has a 62 percent disapproval rate statewide. And the party’s base is shrinking: There are now fewer registered Republicans in California than independents. “Nobody in California beyond the red meat base is going to listen to what Republicans have to say until they publicly renounce Donald Trump and the nationalism that has overtaken the party,” Madrid says. The party doesn’t need to be “saved,” he says, it needs to be “fumigated.”

Rob Pyers, the research director for the nonpartisan California Target Book, says that Trumpism just doesn’t have the numbers to sustain the party. “There seems to be a dwindling core of Republican base voters. They’re still firmly in Donald Trump’s camp, but the moderates and the growing swath of the no-party-preference voters, they seem to be incredibly turned off by the president,” he says, “and they’re voting accordingly.”

The California Republican Party has a chance to change course in late February, when it will gather in Sacramento for its biannual convention. There, its members will elect a new chairperson to replace current party chairman Jim Brulte, who is not seeking reelection. What has historically been a functionary role (Brulte once tweeted that he wanted to be “the most boring Republican Party chair in history”) is becoming a battleground for a familiar tug-of-war. On one side are the officials and and operatives who hope the next chair will free the party from Trump and reclaim the middle. On the other side are conservative diehards who think the path forward is to dig in even deeper. As Sue Caro, a regional vice chair of the state party from Oakland, notes, “A lot of people think the Republicans haven’t fought hard enough. They like fighters.”

In early January, David Hadley, the current vice chair of the CRP, dropped out of the running to head the party. Pyers saw his departure as a foreboding sign. On Twitter, Pyers wrote that the departure of a “[m]oderate, big-tent Republican” would “hasten the party’s assisted suicide in California.”

That left two conservatives in the race. Travis Allen, who ran unsuccessfully for governor in 2018, is known as a charismatic, pro-Trump conservative who has the support of tea partiers. The party’s base and grassroots like him, says Caro, because he’s a clear messenger “who takes it to the Democrats all the time.” Steve Frank, who’s also pro-Trump, is a longtime activist who runs California Political News and Views, a state politics blog with thousands of subscribers. He has deep roots in California Republican politics: He started walking precincts for Richard Nixon in 1960, and says he’s been to almost every state party convention since 1966. (He missed it when he was serving in Vietnam.) “He’s been around a long time,” says Madrid. “He knows where the bodies are buried.”

There’s a latecomer to the race: Jessica Patterson, a behind-the-scenes operator who worked on campaigns for former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and eBay CEO Meg Whitman. She announced her candidacy on January 11, days after Hadley dropped out, declaring that “Democrats are systematically destroying the state I love.” She is the CEO of California Trailblazers, which recruits and trains Republican candidates for state offices and is modeled after House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s efforts to bring more “young guns” into the party.

Allen and Frank are convinced that sticking with Trump will help save their party. In a recent interview with Bryan Anderson of the Sacramento Bee, Allen said that Madrid, Mayes, and other never-Trumpers are the ones who are out of touch and hastening the party’s decline. “They’re all aligned with this Republican establishment that has led our party to almost complete irrelevancy in our state. They are the Republicans telling you that the Republican Party is dead…that you must look and sound like California Democrats to be viable in our state,” he said.

Frank refers to these as “Democrat-light,” or “establishment” Republicans who “would prefer to continue this downward trend toward disrespect, distrust, and incivility” rather than accept that Trump is president. The problem isn’t Trump, he argues, but the Republicans’ inability to field candidates and their lackluster effort to get out the vote. “When you go six years without registering voters, as the state party has done, when you go from 1 million more Republicans than decline-to-state voters in January of 2013 to 700,000 more decline-to-state voters than Republicans in 2018, you have to expect you are going to lose elections,” he says.

Frank notes that in 2016, there were 24 state legislative races without a Republican on the ballot. In 2018, Republicans sat out 41 races. “If you don’t have candidates on the ballot, how do you expect to win elections?” he asks. Frank, who champions Trump’s controversial immigration policies and credits the president’s economic policies for the low unemployment rate, shrugs off his opponents for party chair. He says Allen sees the position as a stepping stone toward the governor’s mansion. He dismisses Patterson as a “staff person” who “represents the no-Trumpers in the party.”

Patterson is seen as the moderate in the race. Right On Daily, a conservative politics blog that supports Allen, accuses her of having the pedigree of “a Liberal Republican Political Operative.” But Patterson’s close ties to McCarthy, whom the Washington Post has called Trump’s “fixer” and “candy man,” make the never-Trumpers worried. “I’m guessing that because she’s so close to Kevin, she’ll have no choice but to toe the party line. There is nobody who is more pro-Trump than Kevin McCarthy at this point,” says Madrid. Mayes is “hopeful” that Patterson can separate the state party from the national party, “but I don’t know if she will.”

Mayes, who won reelection in 2018 as an outspoken opponent of Trump, knows how brutal the infighting over the party’s direction can get: In 2017, he struck a deal with Democrats to pass a cap-and-trade carbon emissions policy. In response, the CRP rebuked Mayes and seven other Republicans who voted for the measure; he was ousted from his position as the Republican Assembly leader and branded a “Cap and Traitor.”

Recently, Mayes says, he’s seen many Republicans leave the party, including former legislators and party officials. “We have so many people who have been fighting the fight so long and have been waiting for something to happen who have said, ‘Enough is enough—I can’t associate with the party anymore,'” he says. “The national Republican message is toxic for running for office in California.” He says he recently heard from a state senator who vowed to leave the party if Allen or Frank win. On the day that Maienschein switched parties, Mayes tweeted that more legislators would leave the party if Allen becomes party head.

Madrid likens this phenomenon to a brain drain: “As the Republican Party shrinks, it becomes more monolithic. It’s the voices of reason and the voices of diversity that leave. The echo chamber gets louder. Now the party has gotten so small that the nationalist voices are all that’s left. The balancing voices of moderation and reason have left—they’re gone.”

With the party convention a month away, both moderates and conservatives are girding themselves for an existential showdown. Mayes believes that, even if Patterson wins, things will get worse for California Republicans before they get better. “I want to believe we’ll be able to get out of the death spiral. Is the party chair going to do it? I don’t think so.” Frank sees similarly high stakes. “The very survival of the Republican Party will be decided at this convention,” he says. “The Republican Party has a choice: survive or suicide.” On that point, at least, they can all agree.