Library of Congress

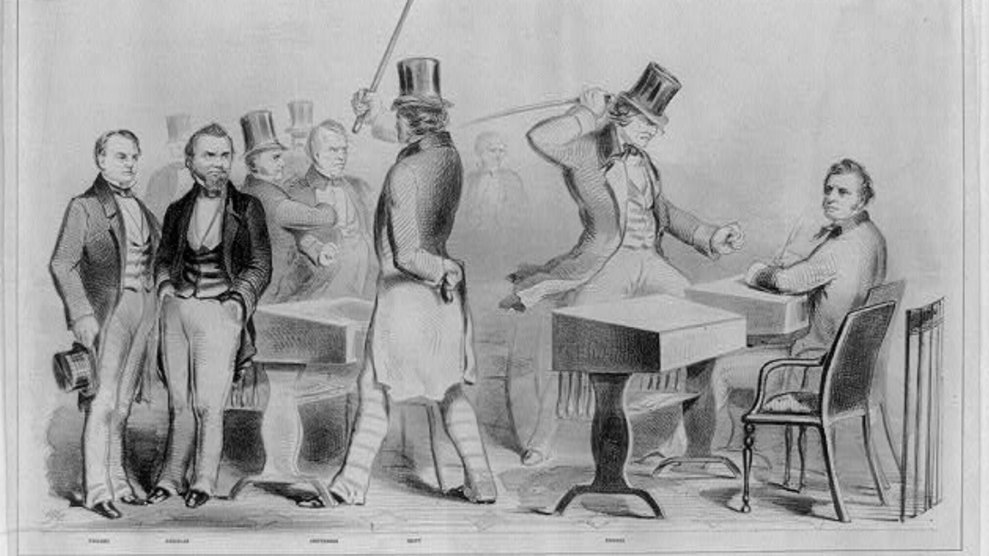

In 1838, Rep. William Graves, a Kentucky Whig, shot and killed Rep. Jonathan Cilley, a Democrat from Maine, and became the only member of Congress to murder one of his colleagues. The events that led to the fatal duel were convoluted and—even by today’s standards—almost breathtakingly stupid, but in her new book, Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War, Yale historian Joanne Freeman distills the incident to its essence. The duel, and others like it, was both a reflection of and a driving force behind partisan and sectional divides that would ultimately cleave the nation in two.

The product of 17 years of research and writing, Field of Blood tells you something you don’t know about something you may have thought you knew—the nation’s long march to the Civil War. Though a few incidents, such as the Graves-Cilley duel and the 1856 caning of Sen. Charles Sumner, have lingered in the history books, the full scope of antebellum violence in Congress has gone untold. Poring through old letters and diaries, Freeman found more than 70 incidents of violence—or threats of violence—between 1830 and 1860. And the violence served a purpose: Threats and brute force were tools by which the Southern slave power exerted its will on the federal government—until the North began to fight back.

Freeman spoke with Mother Jones in December about the book, historical memory, chaos in Parliament, and a man with the nickname “Extra Billy.”

Mother Jones: Where did this violence come from? Was it comparable to the previous era of American politics?

Joanne Freeman: When I was first beginning this project, I started in the 1830s because I knew that in 1838 one congressman killed another in a duel. When I backed up a little bit, there’s still violence—actually the cover of my first book [Affairs of Honor, on the first 10 years of the federal government] has a depiction of congressional violence on it—so it’s not totally new.

But when technology begins to spread and newspapers reach further and faster, what I could see in looking at the congressional record, or the equivalent of it at this time, was that congressmen were thinking more about their audience. That had an impact on it, and combined with the problem of slavery, it just rose until the point that it became a full crisis.

MJ: They were kind of performing?

JF: They were performing, but I try not to say that in the book because it suggests that everything is fake, and part of the point I make is that that kind of humiliation on the national stage—threats and intimidation—matters. Even though the book is about violence, the threat of that violence had an even broader impact. So certainly a lot of the time they knew that they were being watched, but some of the time, that audience was the point. If you do that sort of thing in front of people, it’s going to affect the person you’re doing it to, and if you’re one of the people who have been inflicting that kind of damage, it’s going to prevent other people from getting in the way in the future.

MJ: You connect the violent incidents in specific ways to the ongoing debate over slavery, but it also seems like a recurring theme is that many of the belligerent congressmen were just kind of drunk.

JF: Drunkenness certainly had something to do with it. I don’t think if you were a drunk congressman you were necessarily going to be a violent congressman. They didn’t usually love to have evening sessions of Congress, partly because nobody wanted to still be working in the evening, but also because that was after dinner, and they would drink at dinner, and so very, very often during evening sessions things would, at the least, get ugly. So some of it has to do with liquor for sure.

But it’s not all due to drunkenness. It’s due to the impact of that kind of behavior. There are some congressmen who are notorious precisely because they engage in that kind of behavior, and they get reelected for it. They’re defending the interest of their people, or ultimately, down the road, of their sections. But in one way or another, they’re fighting for what they represent. Some people, particularly early on in the South, wanted their congressmen to fight for them.

MJ: I was struck by Preston Brooks, the South Carolina Democrat who beat Massachusetts Republican Sen. Charles Sumner with a cane in 1856. You write that afterward, people sent him canes from all across the South.

JF: That’s a great example both of the performative aspect of it and the ways in which it’s more than performance. Both North and South had an enormous response to the caning, partly because it came after a string of Southern attacks against Northerners, partly because of the brutality of it, and the fact that it took place within the Senate chamber itself—which Brooks tried to avoid. He tried to catch Sumner outside so that he could avoid precisely what happened, which is the symbolism of a Southern congressman striding into the Senate and beating an abolitionist to the ground. I remember reading through Sumner’s letters, and letter after letter after letter, from adults, from schoolchildren, [they’re] not even sure what to do with their emotions, talking about crying when they heard what happened. The power of that moment for Northerners is easy to underestimate.

The same goes for the other side of the equation. Many Southerners took abolitionism generally—and abolitionists specifically—as an insult, as well as a threat and a danger. There was a feeling that Brooks gave Sumner just what he deserved. Sumner had stood up and made a rousing speech attacking the spread of slavery into Kansas, had insulted the South, had even insulted a few Southern congressmen. So to many Southerners, their response was, “Thank you so much for defending our honor and our interests and silencing him.” There was one letter I found from a woman who was a Northerner, and I believe she married a Southerner, and she says in the letter, “If Brooks had done it anywhere but in the Senate and not over the head, then nobody would have any objections at all.”

MJ: Wow.

JF: Yeah. So there was a way in which it was very much spur-of-the-moment, but there are ways in which there were rules of combat, so to speak. Because although they’re performing, although they’re threatening, although they’re intimidating, although they’re sometimes going into full-fledged violence, nobody really wants to hurt anybody, and nobody wants to destroy the institution of Congress. They’re just trying to get what they want.

They want it to be a fair fight. Thus, that statement: If it hadn’t been in the Senate and it hadn’t been over his head. The official congressional investigative report of the caning actually chides some of the people who knew that the caning was coming because they didn’t warn Sumner so that he could arm himself. Think of that logic.

MJ: The way we learned it in high school was the teacher actually beat a mannequin with a cane.

JF: Wow! That must have had an impact, right?

MJ: It definitely stuck in my head. But I’m curious—do you think it’s stuck in the historical memory in the way that it should?

JF: It took me many years to write this book, and over those years, almost inevitably—I would bet 99.9 percent of the time—when I said I’m writing a book about physical violence in Congress, whoever I was speaking with, wherever they were, if they didn’t know Sumner’s name, they would know there was a guy who got beaten. Typically, they would say, “Wasn’t there that guy who got hit?” and I would say, “Yes, Charles Sumner, and blah blah blah,” and they would say, “Yeah, that’s the one.”

What people have sort of lost is the surrounding story of it. They remembered the fact that it happened because there’s a shock value to it, but all of the context is gone. Ironically, they remember it because wow, there was physical violence in Congress! As the book shows, it was shocking and it was different from some of the other violent episodes, but it certainly was not a big deal only because it was violent.

MJ: What was the point of this? What was the effect of this pervasive violence, aside from making the job a little bit more hazardous?

JF: I suppose the most dramatic one is that as the slavery problem intensifies, Northerners begin to want their congressmen to fight back. When people initially start standing up in some way, they get letters from people back home saying, “Finally there’s a North! You’re acting like a man!” There was a lot of frustration with the fact that responding in-kind [had] seemed to many Northerners kind of barbaric in a way. One of the ways in which this shaped the road to Civil War is that in the mid-1850s, you have the rise of the Republican Party to be the explicitly anti-slavery, Northern party, and they campaign on the idea that they’re going to fight the slave power. There’s a literal dimension to that. When you begin to get increasing numbers of people sent to Congress who say explicitly, out loud, “We’re a different kind of Northerner, you can’t push us around anymore,” that intensified the level of debate in Washington.

Another point that I make in the book is that what’s going on in Washington isn’t some isolated little storm of legislative anger, but clearly the Congress is responding profoundly to what their constituents want. There was a long-ago theory that congressmen were blunderers and they blundered the nation into a civil war. I don’t think that at all. They were doing their job to represent the interests of the folks back home, and the folks back home had an increasingly strong sense of what they wanted. When you put the violence back in the picture, it shows you something of the level of hostility in the national conversation. You can see how deliberate sectional violence, and the rhetoric and the conspiracy theories that go with it, is really becoming woven into the nature of debate. There’s a fight I talk about in the book, a large one, which reporters said looked like warfare.

MJ: This is the one that included the congressman whose nickname was “Bowie Knife”?

JF: John “Bowie Knife” Potter. In 1858. It’s a huge brawl on the floor of the House in front of the speaker’s platform. They were armed, although they didn’t really pull their weapons, so nobody was shot or stabbed. Most of the fights are a handful of guys punching another and they get tangled in a desk or tip over a chair—this was different. This was North against South en masse. This looks like a battle. Congress is representative in a lot of ways, and I think the violence is one way of getting a sense of the state of the nation.

MJ: Did you happen to see the recent incident where a member of British Parliament grabbed the ceremonial mace?

JF: I did!

MJ: What did you think of that?

JF: Given that for a long time I’ve been known as the person writing this book, I became like the central base of anyone I know to send me any legislative misbehavior anywhere around the world. So of course people said, “Joanne, look at what’s happening in Parliament!” I did indeed go watch the footage.

So the mace in and of itself is a symbol; it doesn’t do anything except sit there. The symbolic act of someone striding across the room grabbing it and attempting to leave with it—you can hear them say, “No, no, no!” It’s fascinating when you can watch the same kinds of feelings and political responses to behavior unfold now that echo so strongly with the period that I’m writing about. Although, obviously, the culture of Parliament’s really different, and Americans often were not cowed into silence by the mace.

MJ: Though they tried, right?

JF: When there was a big fight, the sergeant-at-arms often would grab the mace and rush to the point of the fight, and the idea was that it was a symbol that represented Congress in session and it would cow people into backing down because they’d be ashamed of themselves. The mace mattered enough for someone to think that waving it around a bunch of fighting congressmen would have an impact, but it also didn’t matter enough to necessarily really quash a lot of the violence.

MJ: Why did this violence stop? Was the Civil War just the natural endpoint?

JF: Well, it was an endpoint. So when the South secedes from the Union and Southerners stand up and leave Congress, the mood changes. I remember seeing a New York Times editorial that said something like, “Isn’t it a relief to be able to walk down the streets of Washington without your hand on your gun?” Half-joking, but also making a point that the mood of Washington is different with that kind of direct threat gone. In Congress, you see an immediate fall in the level of violence, partly because now the slavery problem is going to be fought out on a different battlefield, and partly because the most notorious bullies are no longer in that institution.

But there are two things that are particularly interesting. One of them is that when the Southern states try to get back into the Union and go to Congress to begin that process, they bring violence with them. There are a handful of incidents in which Southerners attack Northerners for not letting them into the Union or threatening their ability to rejoin the Union, but the dynamics of power have changed so dramatically that they don’t have the power that they once had in this. As a matter of fact, they kind of backfire. The response was, “Look at that barbarian—do we want to let them back into the Union?”

The other one is when the threat of violence ceases, the level of nastiness of language rises. People at the time noted the fact that debate in Congress became particularly rotten and nasty and people were throwing all kinds of insults at each other and said explicitly, well, now that people aren’t afraid of fighting a duel or being challenged to a duel, the language is getting worse. That was long one of the defenses of dueling—that the existence of dueling makes men behave.

MJ: I think my favorite character in the book, even though he’s kind of terrible, is this congressman whose nickname was “Extra Billy.” Who was Extra Billy and why was he extra?

JF: He had more than one federal job at a time, so he was collecting extra money. So “Extra Billy” Smith was basically banking on government positions in a not quite acceptable way. I love the fact that that was just his name!

Extra Billy Smith appears in the book because he attacks an editor. He attacks an editor for calling him a know-nothing in his paper—for basically insisting that he’s an extremist in his politics. They fight—they actually brawl on the street—and there’s a phrase that results from this that appears in the press that’s one of my favorite phrases in the book. People say that the editor’s thumb was “catawampously chawed up” by Extra Billy Smith. Catawampously chawed up! How great a phrase is that? That needs to come back.

MJ: Rep. Jared Huffman (D-Calif.) is proposing to roll back the regulation that allows members of Congress to still carry firearms. Was there ever any talk of doing anything like that back when congressmen were actually using them?

JF: There was once that I could document—there might have been more—and it’s particularly wonderful because of the weird irony of it. I can’t even remember which fight it is that goes on in Congress, but when it’s done and people are trying to figure out what to do to [fix] this problem, one congressman stands up and says, “Perhaps we could put a gun rack in the rotunda and we could hang our guns on the gun rack before we come into the chamber.”

What’s wonderful about that suggestion is it’s Preston Brooks who makes it.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.