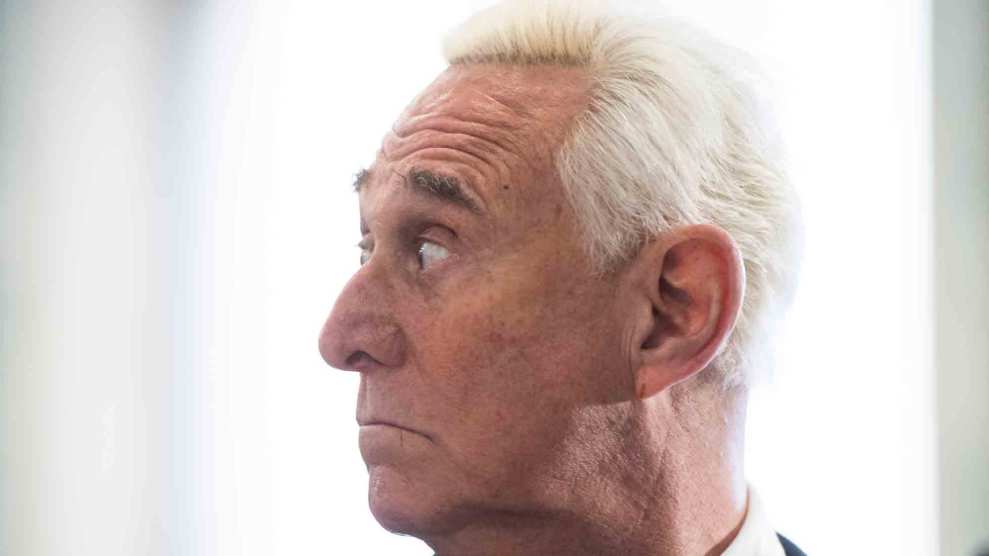

US conservative political activist Jerome Corsi speaks outside the US Federal District Courthouse in Washington, DC, on January 3, 2019. Paul Handley/AFP/Getty Images

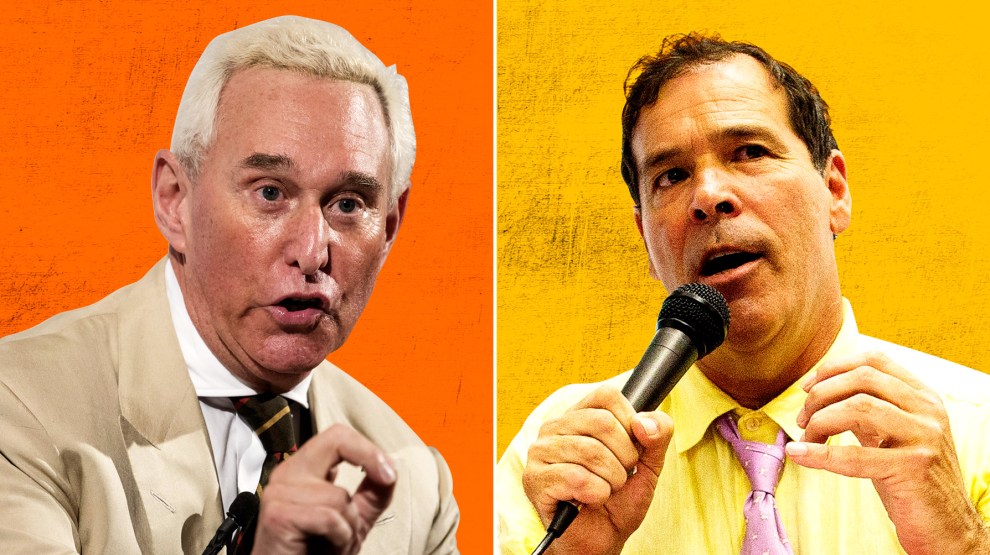

Roger Stone dedicated his 2017 book about President Donald Trump’s election to three people: Richard Nixon, the late president whose face is tattooed on Stone’s back; Juanita Broaddrick, whose claim that Bill Clinton raped her in 1978 Stone revived during the 2016 campaign; and Jerome Corsi, the right-wing conspiracy theorist whom Stone lauded as “a mentor, colleague, and one of the most effective investigative reporters writing today.” The book references Corsi dozens of times.

Stone has a different take on Corsi today. The self-professed Republican dirty trickster, who pleaded not guilty on Tuesday following his indictment by special counsel Robert Mueller for lying to Congress and witness tampering, has recently called his former mentor a “pathological liar,” “Judas,” and “Mueller’s minion.” Corsi, meanwhile, says he is happy to testify about his onetime pal.

Their relationship fractured late last year as the men, under scrutiny in Mueller’s Russia probe, offered contradictory accounts of their efforts to get information on WikiLeaks’ plans to publish emails stolen by Russian hackers from Hillary Clinton’s campaign and other Democrats in 2016. Both are now threatening to sue each other for defamation.

This feud—in which ex-allies famous for spreading false claims denounce each other for defamation—may strike many as heavy on karma and a bizarre sideshow. But the spat does matter for Mueller’s investigation. Though Corsi has provided some information to Mueller, prosectors have accused him of covering up other details of his WikiLeaks-related interactions with Stone. And Stone was indicted for lying to Congress about his dealings with Corsi and how they relate to WikiLeaks. So this sparring match does concern a key part of the Trump-Russia scandal: possible Stone links to WikiLeaks—and whether any of his activity was connected to the Trump campaign.

According to Stone, he and Corsi have been acquainted since 2011. That is when Corsi, an early proponent of the false claim that former President Barack Obama was not born in the United States, began talking to Trump, whom Stone has long advised politically, about birtherism, contributing to Trump’s embrace of the issue. Corsi was also a lead orchestrator of Swift Boat Veterans for Truth, a group that ran a discredited but politically effective smear campaign claiming that 2004 Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry did not deserve his Vietnam war medals.

In 2016, with Stone acting as an outside adviser to the Trump campaign and Corsi writing for right-wing website World Net Daily, the men worked closely together. In his 2017 book, The Making of the President 2016, Stone cites Corsi’s articles on a number of anti-Clinton issues that Stone hyped during the campaign, including questions about Hillary Clinton’s health and claims that Bill Clinton had an unacknowledged black son. Stone is an accomplished conspiracy theorist in his own right; he once wrote a book claiming that Lyndon B. Johnson masterminded the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

In late July 2016, Stone emailed Corsi telling him to “get to” WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, who had just dumped stolen Democratic National Committee emails, to find out what else Assange had planned. Corsi responded on August 2, telling Stone that WikiLeaks had more politically damaging information on Clinton’s campaign and intended to release part of it in October. Corsi also indicated that some of the information would relate to Clinton campaign chief John Podesta. On August 21, Stone tweeted: “Trust me, it will soon [be] the Podesta’s time in the barrel.” That statement seemed prescient when, in October, WikiLeaks began releasing Podesta’s emails—hours after the now-notorious Access Hollywood video emerged.

During the summer of 2016, Stone repeatedly intimated in public that he had inside access to WikiLeaks, saying that he had communicated with Assange. But as investigations into Trump’s Russia ties ramped up in 2017, Stone ran from those claims and insisted he had engaged in no direct interaction with Assange. In testimony to the House intelligence committee and in public accounts, Stone has offered a complicated explanation for the Podesta “in the barrel” tweet, asserting that he had been referring to Podesta’s relationship to his brother Tony, a lobbyist whose clients included Ukraine. Stone said he had based his tweet on research that Corsi had sent him. Stone also maintained that he had merely used Randy Credico, a New York City radio host and comedian, as an informal back channel to Assange during the campaign—a claim that Credico himself has challenged.

Stone and Corsi remained aligned after Trump’s election. Stone helped Corsi land a job at the right-wing conspiracy site Infowars, where Stone was a contributor. Corsi was named Infowars‘ Washington bureau chief, though he lives in New Jersey, receiving a large salary for a journalist: $15,000 a month. At Infowars, Corsi told an associate that he was “working closely” with Stone on the case of Seth Rich, the former Democratic National Committee staffer who was murdered in 2016 in Washington, according to an email provided to Mother Jones. Stone and Corsi were working to cast doubt on US intelligence agencies’ conclusion that Russian intelligence stole the Democratic emails and gave them to WikiLeaks by pushing the unsupported right-wing conspiracy theory that Rich leaked the emails to Assange’s group and was murdered as a result.

The two men’s break came this past November, as Mueller’s team drilled down on Stone’s WikiLeaks contacts, interviewing various associates of the Republican operative. Among them was Corsi, who prosecutors threatened to charge for making false statements about his communications with Stone. Corsi says that he told investigators he had helped Stone concoct a phony explanation for his “time in the barrel” tweet. Corsi asserts he told prosecutors that nine days after Stone’s famous Podesta tweet, Stone had asked him to write a memo on Podesta’s past business dealings. According to Corsi, he told a grand jury that he understood the memo to be “a cover story” to “explain this tweet.”

When Stone appeared before the House intelligence committee in September 2017, he was asked if he had any records about any efforts to interact with WikiLeaks. He said there were no such records, and failed to reveal his emails with Corsi about WikiLeaks. And he did not disclose that he had asked Corsi to connect with WikiLeaks. Essentially, according to the Mueller indictment, Stone concealed from the committee his attempt to use Corsi to reach WikiLeaks. Mueller’s indictment of Stone also intriguingly notes that “a senior Trump Campaign official was directed” to ask Stone to make contact with WikiLeaks. This raises the question of whether Stone’s attempt to use Corsi to contact WikiLeaks was connected to Trump or top campaign officials.

Stone also told the intelligence committee that it was Corsi’s memo that had led to his tweet, claiming that Corsi had communicated the crux of the memo’s content prior to the tweet. But Corsi, who said he received immunity from Mueller for this testimony, presented an account that implicated Stone in perjury.

Stone has called Corsi’s cover-story assertion “categorically false and ludicrous not to mention illogical.” He also says that any false statements he made to Congress were “immaterial and without intent.”

Since Corsi has publicly undercut Stone’s testimony, Stone has attacked him frequently and viciously. On Instagram and Facebook, he has called Corsi a liar and suggested Corsi had a drinking problem. After receiving questions from the Washington Post indicating that Mueller was looking into whether Stone had arranged Corsi’s hiring at Infowars in an effort to buy Corsi’s silence, Infowars published an article denying that its payments to Corsi were intended as hush money and asserted that he had been dismissed from his job in June “because of his generally poor work performance” and other shortcomings. In a statement included in that story, Stone said Corsi “was fired after a drunken meltdown in a Washington DC restaurant” last year.

Following these attacks, Corsi told Mother Jones he might file a defamation suit against Stone and Infowars. “My patience is thin,” he says. “I’m not going to put up with defamation and efforts to hurt my reputation.” (Corsi, who sued the Washington Post last week, also said he may sue Politico, the Daily Caller, and Breitbart over what he claims is inaccurate reporting about him.)

Stone has also suggested he may sue Corsi. “Lies have legal consequences,” Stone wrote on Instagram recently. “Stay tuned!” Stone kept up his attacks even after his January 25 arrest. On Friday night, hours after he was released on bond, Stone called Corsi a “Judas” in an Instagram post. This week, Corsi lobbed another bomb at Stone, asserting in interviews, including an MSNBC appearance on Monday, that on October 7, 2016, as soon as the Access Hollywood video was released, Stone asked him to contact WikiLeaks and get the group to release the Podesta emails to distract from the news of Trump boasting of sexually assaulting women. Corsi told Mother Jones that his phone records show he had three phone calls with Stone that day.

Still, Corsi seems to be holding back in his beef with Stone. Despite implicating Stone in an effort to mislead the intelligence committee and accusing him of defamation, Corsi in interviews with Mother Jones stopped short of calling Stone a liar. “I don’t dispute Roger’s perceptions,” he says. “Roger just has a different perception of things than I have.”

Corsi and Stone do retain a shared interest in one element of the scandal. Both now claim that the information on WikiLeaks’ plans that Corsi gave Stone in August 2016 was based on nothing but Corsi’s intuition. That is, Corsi says he figured out on his own that Assange had received stolen Podesta emails. (His explanation is complicated and based on the claim that he analyzed certain facts about the Democratic National Committee servers, though Podesta’s Gmail account, which was hacked, was not linked to the DNC network.) Corsi insists that he received no guidance from WikiLeaks or from intermediaries who might have known details of the hacked material that Moscow gave the group.

Corsi says that prosecutors “had a hard time accepting” this story, presumably finding it improbable that Corsi merely deduced what turned out to be highly accurate information about WikiLeaks’ plans.

One of the major questions hanging over the Corsi-Stone blow-up is why Stone sought to conceal his WikiLeaks contacts with Corsi, pointing instead to Credico as his back channel. Why cover that up?

What’s clear is there’s more to the story of Corsi and Stone’s still-murky interactions during the 2016 election—and thanks to their feud, the public may end up hearing about it.