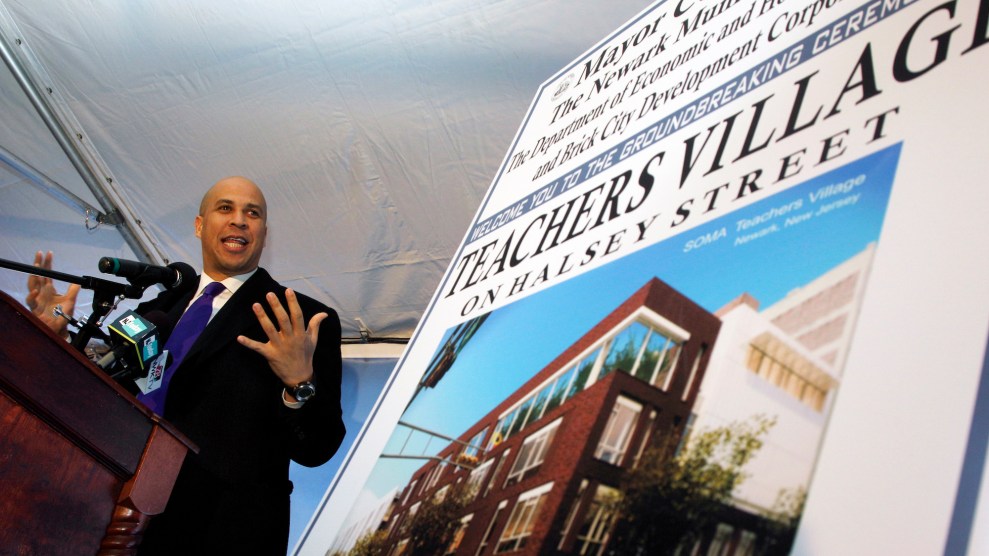

Former Newark Mayor Cory Booker speaks during groundbreaking ceremonies for a mixed-use complex of charter schools and teacher housing on February 9, 2012.Mel Evans/AP

In the spring of 2012, Cory Booker delivered the keynote address at the third annual School Choice Policy Summit at a Westin hotel in Jersey City, New Jersey. For a half hour, the then-Newark mayor told hundreds of attendees dining in the hotel ballroom that the traditional public school system “still chokes out the potential of millions of children…Your destiny is determined by the zip code you’re born into, [and] some children by law are locked into schools that fail their genius.” The most promising solution, he said, was one aligned with the sweeping educational reform he was currently undertaking in Newark that was replacing failing neighborhood schools with publicly funded, privately managed charters that students could opt into based on their desires and needs.

Booker’s address that evening was notable for a number of reasons. He was one of the only Democrats speaking in a lineup that included Louisiana GOP Gov. Bobby Jindal and Fox News commentator Juan Williams. The school choice plan he championed had become a plank of the Republican platform, while many of his fellow Democrats, who generally preferred direct investment in public education and enjoyed political backing from teachers’ unions, opposed it.

And then there was the group that organized the event. His appearance that evening was at the invitation of the American Federation for Children, a group chaired by Betsy DeVos. Booker told attendees he’d been involved with AFC “in its most nascent stages,” and his relationship with the DeVos family dated back to his days on Newark’s city council. DeVos, a Republican megadonor, had become known as one of the fiercest proponents of school choice—especially of for-profit charter schools and voucher programs that would allow students to use public funds to attend private schools. She also addressed the group that evening, and in a press release announcing the event’s speakers, DeVos, who had served with Booker on the board of AFC’s predecessor organization, said she was “proud and honored” to include Booker in the “committed group of education leaders who have courageously stood up to put the interests of children first by supporting expanded educational options for families.”

Nearly seven years later, Cory Booker has announced he would like to be the Democratic candidate for president in 2020, and Betsy DeVos is in her second year as President Donald Trump’s controversial secretary of education, still championing school choice as one of the priorities of her administration. Booker’s vision once enjoyed traction in Democratic circles, particularly under President Barack Obama, whose Education Department implemented policies to expand charter growth. But today, Democrats are backing off their support, especially given the wave of teachers’ protests that has renewed attention on long-term divestment in public education. For example, Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.), who’s likely to seek the 2020 Democratic nomination, tweeted his support of the Los Angeles teachers’ strike that had been organized, at least in part, in opposition to the city’s reliance on charters, and included a link to a Jacobin essay about the dangers of school privatization.

“Charter schools have become much more politicized than they were 5 or 10 years ago,” says Jon Valant, an education fellow at the Brookings Institution who has studied the politics of school choice. “Trump didn’t say much about education policy, with the exception of the fact that he was generally supportive of school choice. And then he nominated a secretary of education whose only real experience with education has been with school choice. Having Trump and DeVos attached to the ideas of charters and choice have changed the minds of a lot of Democrats.”

But as the party moves on, Booker has not. He remains a staunch defender of school choice, a policy he believes levels the playing field for low-income students whose local schools fail to realize their academic potential. His stance has put him on the opposite side both of teachers’ unions and other dependable Democratic allies, like civil rights groups, which worry that charters may actually exacerbate the inequality they were established to address. And while his ties to some of the right’s most ardent school choice advocates have long been known—attracting particular scrutiny during DeVos’ fraught 2017 confirmation—the shifting politics makes the 2020 contender an outlier among his fellow contenders, whose records align more closely with the current moment in this perennial education debate.

School choice hasn’t always been controversial. In 1988, when Booker was an undergraduate at Stanford University, the American Federation of Teachers president Albert Shanker proposed charter schools as laboratories where teachers could test out new teaching methods before sharing them in traditional school settings. Civil rights reformers in Milwaukee, meanwhile, worked with Democratic allies to establish the nation’s first school voucher program in 1990 so that low-income minority students, otherwise stuck in the failing public school assigned to their neighborhood, could use public funds to attend private schools.

Booker’s interest fits squarely in that latter push. After graduating from Yale Law School in 1997, Booker moved into low-income housing in Newark’s rough-and-tumble Central Ward and worked as an attorney for the Urban Justice League before winning a seat on the City Council in 1998. It was there that Booker first proposed vouchers as a means of revamping the city’s failing public schools, citing the Milwaukee example as rationale for his support. “It’s one of the last remaining major barriers to equality of opportunity in America, the fact that we have inequality of education,” Booker told the New York Times in 2000. “I don’t necessarily want to depend on the government to educate my children—they haven’t done a good job in doing that. Only if we return power to the parents can we find a way to fix the system.”

But the decade between Shanker’s proposal and Booker’s advocacy politicized school choice and turned an educational experiment into Republican dogma. Conservatives appreciated the notion of imposing market discipline and choice on public education, which had the added benefit of taking away another government program and replacing it with the private sector. Their enthusiasm for private school vouchers and for-profit, privately managed charters took place at the same time that teachers’ unions began to see the experiment as a drain on public resources and their nonunionized workplaces as bad for their profession and their students.

In 1999, when he was still a city councilman, Booker worked with a conservative financier and a New Jersey Republican mayor to co-found Excellent Education for Everyone, a group dedicated to establishing a school voucher program in the Garden State. The following year, Dick DeVos—the Republican megadonor, school choice evangelist, and husband to the nation’s 11th education secretary—invited the 31-year-old Newark councilman up to his home base of Grand Rapids, Michigan, to speak in defense of a ballot measure that would lift the state’s ban on school voucher programs. “We wanted someone who wasn’t from the suburbs,” DeVos explained of Booker’s interstate invitation—not knowing, perhaps, that his guest grew up in the affluent suburbs of Newark. Bob Braun, a columnist writing for Newark’s Star-Ledger, observed that Booker fit in this group “about as comfortably as Madonna in a home for retired nuns.” Reflecting on the experience to The New Yorker, Booker said, “I became a pariah in Democratic circles for taking on the party orthodoxy on education.”

Booker’s association with the DeVos couple continued as he progressed from City Council to Newark’s mayoral seat in 2006 to the US Senate in 2013. In the mid-2000s, Booker and DeVos served together on the board of directors of Alliance for School Choice (AFC), the precursor to the American Federation for Children, which DeVos eventually chaired. Booker twice spoke at the AFC’s annual School Choice Policy Summit: once in 2012 as a mayor and again in 2016 as a senator. DeVos congratulated Booker and other school-choice-minded politicians in an AFC press release that followed Booker’s 2014 Senate win. Booker, in turn, was complimentary of the initiatives the American Federation for Children pursued under DeVos’ leadership.

But a belief in school choice did not necessarily mean a commitment to school vouchers, and here is where Booker and DeVos parted company. When Booker ran for mayor in 2006, he distanced himself from them: “My plan right now doesn’t include having anything to do with vouchers,” he said. Instead, he favored a system of publicly funded charters that replaced failing traditional neighborhood schools—one accountable to student outcomes, not teachers’ unions’ demands. During his second term as mayor, with $100 million from Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and millions more from donors on both sides of the political aisle, Booker replaced many of the city’s neighborhood schools with charters, recruited teachers and principals through national school reform organizations like Teach for America, and weakened existing tenure protections for teachers by tying job performance to student outcomes. The early reviews were poor: Student performance worsened in the short term, parents panicked over student reshuffling, and, as school choice detractors had warned, the district schools that remained served a disproportionate number of students who needed the most help.

By this time, Booker’s vision was in keeping with mainstream Democratic policy. Arne Duncan, Obama’s Education Department secretary, promoted a similar model for schools nationwide. Several Democrats, including Booker, supported this—even as teachers’ unions, longtime Democratic allies, did not. DeVos, meanwhile, had successfully lobbied state legislatures across the country to adopt school choice models that relied heavily on vouchers and minimally on regulation and accountability. In her home state of Michigan, roughly 4 out of 5 charter schools were run by for-profit companies. “There’s a distinction between Obama-style charter schools, which are public and have accountability measures, and Trump-DeVos style, which are for-profits and don’t,” explains Shavar Jeffries, the president of Democrats for Education Reform, a group that, like Obama and Booker, advocate public charters as a means for education improvement.

But those distinctions grew fuzzy during the 2016 presidential election as Democrats took a hard line on the school choice debate. Hillary Clinton surprised pro-school-choice allies by voicing opposition to for-profit charters early in her campaign. Meanwhile, civil rights groups, which once backed charters as a means of leveling the playing field, pulled back: The NAACP and Black Lives Matter organizers both called for a moratorium on more charter schools, citing concerns about investment in public education and practices that promote racial inequality. Teachers’ unions continued to beat the drum that the school choice experiment had led to a divestment in traditional schools that left the nation’s neediest children high and dry.

Trump’s victory and his nomination of DeVos only heightened concerns—and renewed media scrutiny of Booker’s ties to DeVos. The New Jersey senator was initially mum when Trump picked her, but ended up joining his Democratic colleagues in rejecting her nomination. He cited concerns about her answers to questions about the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights on “issues of equity that were unacceptable to me,” Booker said. Even so, he still affirmed his support for school choice in the process. “I didn’t want to support her to be the secretary of education, but when it comes to my record for supporting what I believe, that any child born in any zip code in America should have a high quality school…I haven’t changed one iota,” Booker said in an interview with CNN after the confirmation hearings.

Then, in 2018, teachers across the country walked out of their classrooms to demand greater investment in public education, pointing to low wages, small school budgets, and large class sizes as symptoms of systemic divestment. Protests that began in West Virginia inspired similar movements in Arizona, California, Colorado, and Oklahoma, and the efforts have been viewed, by and large, as successful. There isn’t a straight line connecting the walkouts to DeVos and charter schools, Brookings’ Valant explains—charter school policy varies widely across states and cities. “But where I think this is all connected is the teachers’ unions feel more emboldened to oppose charters than they have in the past because the public sees charters as tied to DeVos,” he says. “It makes it easier for unions to mobilize public opposition to charter schools.”

Democratic voters may join them. A 2017 Gallup poll found that 48 percent of Democratic voters supported charter schools, down from 61 percent five years earlier. A ballot measure to lift the cap on charter schools in Massachusetts was handily defeated that year—a measure other 2020 hopefuls, Sens. Elizabeth Warren (Mass.) and Sanders, both opposed. The outcomes of the 2018 midterms offer a vision of how the new political environment has played out. Teachers’ unions, buoyed by the voting public, secured victories in states once thought to be inhospitable to their cause. Democrat Tony Evers, Wisconsin’s former state superintendent of education, ousted Republican union-buster Scott Walker in a race dominated by concerns over the underfunding and understaffing of the state’s public school system. Kendra Horn shocked politicos when she flipped an unlikely House seat in Oklahoma, aided by a last-minute $400,000 advertisement blitz from former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg that tied GOP incumbent Rep. Steve Russell to public school decline.

The members of the nascent 2020 field have records that indicate they’ve read the room. “Sen. Warren has worked relentlessly on the issue of student debt and higher education and how an economy has to work for all,” Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers, explains. “Sen. Harris has worked on education. Sen. Brown is working hand in hand with us on the dignity of work. We’ve worked with Sen. Gillibrand on issues of campus sexual assault. Even right now, there’s a lot of people in this race who actually have a very pro-public-education lens with which they look at these issues.” Nearly every Democratic contender, including Booker, tweeted solidarity with the Los Angeles teachers (though none of them directly tied the strikes back to charter schools). “I think most of these candidates want to be understood and identified as progressive, and to do that right now is not to actively support charter schools,” Valant says.

Will Booker be among them?

“Maybe Sen. Booker will, maybe he won’t,” Weingarten explains. “He’ll have to answer a lot of questions.” Lily Eskelsen García, the president of the National Education Association, wouldn’t comment on individual candidates beyond acknowledging that the NEA is in the process of meeting with announced and prospective 2020 contenders. But she and her fellow NEA members are well-acquainted with each candidate’s record, and for them, the top priority will be the vision they suggest going forward. “They’ll want very much to make a case for their agenda as president, which may be very different than their agenda as mayor of Newark,” García says. “And we want to hear, ‘So, where are you going on this agenda of privatized education?’”

Consider Diane Ravitch, who served as an assistant secretary of education under President George H. W. Bush. Ravitch had been a staunch proponent of No Child Left Behind but later changed course, renouncing charter schools and test-based accountability as a means to educational improvement. “When she saw the effects of the reform agenda, she turned around and said just as quickly and strongly, ‘I made a mistake,’” García explains. “It would be interesting to see which politicians, Democrat or Republican, are willing to be that honest.” This week, another school reform-minded mayor, Chicago’s Rahm Emanuel, also withdrew his support for the practice, explaining his reasons in an essay he wrote for The Atlantic.

So far, Booker has taken neither Ravitch’s nor Emmanuel’s path. Though he’s been relatively quiet on the subject of school choice as of late, he’s been pushing back against the characterization of his school choice project as a failure. As he’s prepared for a 2020 run, Booker has twice sat down with education website The 74 to defend his work in Newark, citing new research that attributes the educational gains of the city’s students to the closing of low-performing schools and the introduction of charters. “I’ve never seen such a disconnect between a popular understanding and the data,” he said in an interview this week. “I can find no other urban district with high poverty—with high numbers of kids who qualify for free school lunches—that has shown this kind of dramatic shift in a 10-year period.”