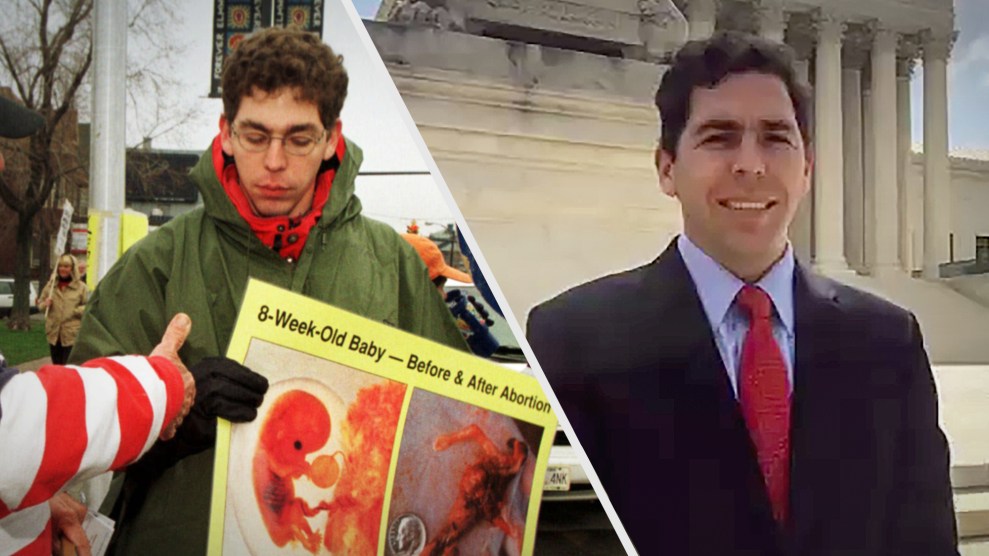

Mother Jones illustration

One November afternoon in 1998, about 20 anti-abortion protestors gathered outside a minister’s home on a quiet, tree-lined street in a Madison, Wisconsin, suburb. Among them was 23-year-old Matt Bowman, a recent college graduate who had come to town the year before to join a pro-life group, hoisting a large picture of a dismembered fetus and a video camera he said was rolling for his own protection. Others in his group proudly carried placards showing stillborn fetuses with decapitated heads.

The demonstrators had chosen their target, Rev. Michael Schuler, because of two sentences the Unitarian minister had written in a newspaper column arguing that voters should look beyond abortion and focus on issues like economic inequality, the environment, and health care.

Bowman and his crew disagreed. Schuler’s wife spotted the protestors and called her husband at church, worried about the safety of their son attending school nearby. “This was a time in which abortion clinics were being bombed,” recalls Schuler. “We were concerned. We had no idea who these people were and we didn’t know what their intentions were.”

The reverend sped home in his Honda Civic while Bowman spoke to a local reporter: “We are here because this is a man representing himself publicly as a member of their religious community, and yet he is excluding pre-born children from the human family.” Soon, a police officer arrived on the scene to break things up and take a report.

The protest was just one of at least 14 run-ins with the law that Bowman had over a five-year period between 1996 and 2001, including arrests during abortion and other protests, police encounters outside abortion clinics and private homes, and one conviction resulting from protesting homosexuality. Court and law enforcement records from the District of Columbia, Florida, Michigan, and Wisconsin record Bowman’s arrests and his targeting of clinic workers, security guards, and patients, sometimes blocking their attempts to receive or provide constitutionally protected reproductive health care. His protests came during a period when American clinics were targeted with unprecedented anti-abortion violence, as he maintained affiliations with pro-life leaders and organizations who’d become known for extreme rhetoric and aggressive clinic blockades.

While the incidents have not previously been reported, Bowman, now 43, seems to have largely put aside such protests as he climbed the legal ladder—clerking for future Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito, arguing major anti-abortion cases in federal courts, and most recently, joining the Trump administration as deputy general counsel at the Department of Health and Human Services.

Bowman has advised HHS in the high profile Garza v. Azar case challenging policies restricting detained migrant girls’ abortion access. According to records obtained under litigation by the pro-choice nonprofit Equity Forward, Bowman gave extensive legal advice to the embattled architect of those policies, former Office of Refugee Resettlement Director Scott Lloyd, as he attempted to block at least seven unnamed girls, including a rape victim, from seeking abortions and made frequent personal interventions encouraging girls in ORR custody to give birth. (Lloyd has since been reassigned within HHS.) While federal courts have three times blocked implementation of Lloyd’s policy, HHS has kept it on the books while fighting in court to reinstate it. Its latest appeal is now under consideration by the federal appeals court in Washington, DC. Bowman attended the latest oral arguments in the case this fall.

In his time at HHS, Bowman has also helped craft rules aimed at weakening Obamacare’s contraceptive mandate. Last month, a federal judge blocked the policy from going into effect, setting up more court challenges.

Bowman’s police record reflects the depth of his anti-abortion views and a willingness to break the law noteworthy for an attorney playing a key role at the main federal agency in charge of reproductive services. An HHS spokesperson declined to make Bowman, who did not respond to detailed requests for comment, available for an interview.

Matt Bowman’s booking photo from a 1997 Florida arrest

“What HHS sanctioned Scott Lloyd to do in the Jane Doe case was blatantly unconstitutional,” says Brigitte Amiri, an American Civil Liberties Union attorney representing girls in ORR custody. “If Matt Bowman has a history of flouting the law with respect to his advocacy, then it should come as no surprise that he would flout the law when he was given a position of power at HHS.”

Bowman’s anti-abortion activism began in the mid-90s while studying physics at the University of Dayton, a Catholic institution in Ohio. He joined the campus chapter of Students for Life, moving into a house reserved for members. One spring, Bowman led a protest they dubbed the “Cemetery of Innocents,” transforming a campus plaza into a makeshift graveyard symbolizing aborted fetuses.

He also began attending events sponsored by Collegians Activated to Liberate Life (CALL), a group that organized weekends of anti-abortion action in Midwestern cities, where some members would distribute graphic leaflets, stage clinic sit-ins, and glue clinic doors shut. The summer before his senior year, Bowman was part of a CALL missionary team to set up a chapter in Russia’s Far East and help spread the “gospel of life.” Bowman graduated with honors in 1997, having moved to Madison, Wisconsin, CALL’s home base, and settled in a house of fellow CALL activists. Bowman, another recent graduate named Will Goodman, and two others launched what one CALL newsletter described as a “Christian solidarity” effort in Madison deploying “direct action” to protect fetuses. In another CALL bulletin, Bowman called on his fellow activists to make “a radical choice” to face “persecution”—lawsuits, even jail time—in the name of the “pro-life struggle.” He compared their efforts to those of German families who hid Jews during the Holocaust or students who fought for racial equity during the civil rights movement. “Are we not heir to their place in society, and facing a much greater injustice?” Bowman asked.

Decades later, the résumé Bowman submitted to HHS seemed to allude to this period of his life, though he refrained from mentioning CALL or Operation Rescue, another extremist anti-abortion group that Bowman worked with at the time. Instead, the résumé says he was a “full-time pro-life volunteer” from 1997 to 2000 for a Madison, Wisconsin, group he identified as The Solidarity Project. State incorporation records reveal no trace of such entity, nor does a search of Wisconsin news coverage from the era.

Over those three years, Bowman had a dozen recorded encounters with Madison police while engaged in pro-life activism. Bowman told police during one such incident that local sympathizers funded his full-time advocacy, along with an anti-abortion organization that Bowman refused to disclose.

The bulk of Bowman’s legal trouble stemmed from nearly two years of almost daily protests outside Meriter Hospital, which leased facilities to the county’s only abortion clinic. In May 1998, a hospital worker called the police after Bowman, holding graphic abortion posters, blocked her route to the building housing the clinic. When a cop showed up and asked him to keep his posters “out of people’s faces,” the cop noted in a police report that Bowman took “a rather sour note.” In another incident three months later, a hospital driver told police that Bowman and another CALL protestor had blocked a van from the facility’s driveway. Later, Bowman targeted a Meriter security guard, showing up outside the hospital and his home with signs singling him out as a “Nazi Death Camp Guard.” In July 1999, Bowman tried to hand anti-abortion literature to two women and engage them in conversation as they entered the hospital. When they said they weren’t interested, they called the cops; one women reported that Bowman “got in my face.” The responding officer told Bowman he could not block or hound patients if they refused his overtures. Bowman “became argumentative,” the officer reported, and let up only when told one more complaint would earn him a disorderly conduct citation. In March 2000, Daniel Martin, another Meriter guard, told police that Bowman and other demonstrators had trespassed at his home and possibly rifled through his mail. Later that month, Martin again called police after Bowman arrived at the Meriter campus with a large poster reading “Daniel Martin Liar-Murderer-Coward!” on one side and featuring graphic fetus photos on the other. Bowman was the subject of another police call at Meriter later that spring when a female patient claimed that Bowman “verbally harassed” her on the topic of “abortion vs. adoption.” The responding officer arrived to find Bowman fleeing the scene and the woman still agitated.

“We did everything we could to protect both our patients and our staff from having to interact with these people,” says Dr. Dennis Christensen, who ran the clinic housed at Meriter. “I’m not intimidated easily by that kind of activity. But I was annoyed that it was an extra thing we had to deal with to provide medical care. It took time away from us taking care of the patients.” Christensen says he isn’t surprised one of those protestors is now working on abortion policies at President Donald Trump’s HHS, and questions his appropriateness for the job: “I’m concerned about anybody who is in there who is not interested in the patient’s welfare. That’s what the health department is supposed to be all about.”

Bowman participated in similar actions across Madison. In March 2000, Bowman stood outside a high school, handing out invitations to an abstinence lecture by that year’s Miss Wisconsin. After Bowman, in front of dozens of students, responded with “aggressiveness” to inquiries about the flyers, the principal called police. When one officer arrived on the scene, she quickly called for backup. According to her written report, Bowman grew evermore agitated, interrupting and yelling that she was violating his rights, and seeming to threaten physical aggression. After three more officers arrived, they arrested Bowman for disorderly conduct and took him to the station but ultimately declined to file charges. In October 1998, Bowman and a handful of others picketed a Republican House candidate’s office after she’d been accused by pro-life forces of supporting a commonly used method for late abortions. A nearby pet store owner called police, saying customers had complained about “harassing protestors.”

Bowman’s arrest record wasn’t limited to the Midwest. In April 1996, Bowman traveled to Washington, DC, where court records show he was among eight young anti-abortion activists arrested for unlawful entry after occupying the office of Sen. Bob Dole, then the presumptive Republican presidential nominee. The demonstrators refused to leave until he promised to support a constitutional amendment banning abortion in any circumstance, even when a woman’s life is in danger. After the Hart Senate Office Building closed, Capitol Police dragged the crew—who went limp during arrest—to a waiting police van. Four days later, Bowman failed to come to his DC court date; the judge issued a bench warrant for his arrest and set bond at $500. Bowman never appeared, and the warrant remained active until April 1999, when it automatically expired. Four years later, prosecutors officially closed the case, just a few months after Bowman graduated from law school.

In December 1997, Bowman joined up with the Reverend Flip Benham, the national director of the extremist anti-abortion group Operation Rescue, for a major demonstration outside Florida’s Disney World. The pair helped lead a group of about 100 high schoolers in protest of what they called the “Tragic Kingdom”: Disney’s promotion of “homosexual life” as manifested in its movies, in gay-friendly days at its parks, and on its networks like ABC, where Ellen DeGeneres’ sitcom character had just come out. Bowman, Benham, and their teenage crew blocked traffic, waved signs (“Choose Jesus over Mickey”), and thrust “Why Boycott Disney” pamphlets at annoyed drivers.

As cars sat backed up for two miles, cops arrived. After ignoring warnings, Bowman and Benham were charged with obstructing traffic and throwing advertising material and booked into county jail. Bowman eventually entered a no-contest plea to the obstruction charge and paid a fine; the other charge was dismissed.

A supporter of abortion rights offers to shake hands with Matt Bowman during an April 1999 rally in Buffalo, New York.

David Duprey/AP

In July of that year, he helped organize another Operation Rescue anti-Disney protest about an hour outside of Madison. When a sniper murdered abortion provider Dr. Barnett Slepian outside of Buffalo, New York, in October, Operation Rescue launched plans for a series of anti-abortion demonstrations marking the six-month anniversary of his killing. In the face of local civic groups who objected to Operation Rescue’s plan to turn the city into an abortion “battleground,” Bowman came east for the occasion, starting the week off as the lone anti-abortion protestor walking the sidelines of a pro-choice rally. He held a photo of an aborted fetus and told a local reporter he had come to protest peacefully, while police erected barricades and kept patrols outside a nearby women’s health clinic.

“Matt Bowman helped create and also exploited the climate of terrorism and intimidation against people who were providing legal health care in the mid- to late-90s,” says Mary Alice Carter, the executive director of Equity Forward. “HHS is supposed to support the well-being of people in America. I fail to see how someone who has the view of women, health care professionals, and LGBTQ people that he does could be fit to serve in HHS and to be objective when it comes to those populations.”

In the summer of 2000, Bowman moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, to join the first class at the Ave Maria School of Law, a new institution created by Domino’s Pizza founder and conservative Catholic donor Tom Monaghan. With a curriculum developed with the help of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, Bowman excelled, making the dean’s list each semester, joining the law review, and winning awards. He would graduate as valedictorian.

Throughout law school he continued to protest at clinics. On a return visit to Madison during the spring of his first year, Bowman led a demonstration outside the home of a gynecologist, leaving once police arrived. In Ann Arbor, he regularly picketed the Packard Women’s Clinic, often bringing a camcorder to record patient arrivals. A few times when clinic staff or visitors to nearby businesses tried to block the camera, Bowman himself summoned the Ann Arbor police to file assault and battery charges, once alleging that a clinic worker threw salt at his face. A 17-year-old girl told police that she’d been upset after witnessing Bowman interact with two younger girls walking out of a nearby costume shop: After they asked Bowman about his signs, he told them that employees of the clinic were murderers and that the pictures showed what they would do to babies.

Bowman’s actions grew bolder. According to police reports, he began approaching women as they parked outside Packard, following them from their cars to the clinic’s entrance and “harassing” them about abortion even if they asked to be left alone. In June 2002, a nurse at the clinic, Jill Toney, told police that Bowman had been following her “at a close distance” when she entered the clinic, calling her a murderer, telling her she would go to hell, and placing flyers on her arm or in her pocket after she declined to take them. Toney had grown so frightened of him that she’d taken to asking a manager to escort her. Of all the demonstrators who regularly protested Packard, Bowman, she said, was the only one that made her feel “uncomfortable and intimidated.” Five other female employees at the clinic, Toney said, had also felt threatened by him. She said that in addition to videotaping patients and employees, sometimes concealing the camera in his car, Bowman had also begun recording employees’ license plates. Toney told police she only reported Bowman after enduring months of his behavior, in hopes that he would be prosecuted for harassment and intimidation. Local prosecutors decided Bowman’s behavior did not rise to the level of criminal harassment, but advised she speak with a lawyer about filing a civil claim. (It’s unclear if she did; Toney did not respond to requests for comment.)

In the fall of 2003, Bowman, a new law graduate, joined the Michigan bar. After several federal judicial clerkships, including one with Samuel Alito, then a circuit court judge, in 2006 he joined the Alliance Defending Freedom, a conservative Christian legal advocacy group. While an absence of further police reports suggests he was no longer an aggressive front-line protestor, as a senior attorney at the firm’s Center For Life, he continued to wage anti-abortion battles, successfully representing clients in cases opposing Obamacare’s birth control benefit, state abortion access laws, and laws relating to the expression of anti-abortion views.

In 2009, Bowman returned his focus to Meriter, spearheading the ADF’s efforts to stop the hospital from opening a clinic that would perform second-trimester abortions in cooperation with the University of Wisconsin. Bowman wrote a letter to the presidents of the hospital and the university arguing that the plan would force pro-life students and employees “to violate their consciences by participating in the killing of preborn, developed babies.” (He also sent a copy to his future employer, the Department of Health and Human Services.) Following a persistent campaign, Bowman and the ADF took credit when Meriter and UW, citing concerns over clinic security, nixed the plan.

After the US Supreme Court ruled in the ADF’s favor in a 2014 case striking down a Massachusetts law that established a 35-foot no-protest zone around clinics, Bowman declared victory from the steps of the court. “Massachusetts had passed a law that censored pro-life free speech,” he said. “The court decided that members of the public should be able to quietly offer information to other citizens even if the government disagrees.” Bowman and the ADF used the Supreme Court’s ruling to overturn what they dubbed “censorship zones” outside clinics in New Hampshire, Pittsburgh, and his old stomping grounds in Madison.

Since his appointment as HHS deputy general counsel in March 2017 by the Trump White House, Bowman has set to work turning pro-life legal arguments into federal policy. Last summer, for instance, he teamed up with White House health care policy adviser Katy Talento, a longtime anti-birth-control advocate, to craft the administration’s October 2017 rules gutting Obamacare’s contraceptive mandate.

Bowman arrived at HHS alongside a number of other longtime conservative activists appointed by Trump, including Lloyd, who took the post of director of the Office of Refugee Resettlement after a decade spent working in the anti-abortion legal world. ORR oversees the approximately 12,000 unaccompanied migrant minors who enter the United States undocumented each year, and one of Lloyd’s first actions was to transform ORR’s policies on girls in custody who request abortions, in place under both the George W. Bush and Barack Obama administrations, to require his direct approval. Email records obtained in a FOIA lawsuit by Equity Forward confirm that ORR is part of Bowman’s legal “portfolio” of internal clients. According to these records, along with email logs obtained by the ACLU, Bowman appears to have advised Lloyd on the rollout of the policy, and, in October 2017, its application as the agency battled an unnamed 17-year-old girl housed in Texas seeking an abortion. In a case that quickly garnered national attention, outrage, and protests, the woman was finally able to get an abortion, following multiple appeals by Trump administration lawyers, when she was nearly 16 weeks pregnant.

While the email records reflect routine lawyering, says Kathleen Clark, a law professor and legal ethics expert at Washington University, she says Bowman’s past activism—especially instances when he physically blocked individuals from engaging in lawful conduct, like entering a clinic—shows a “disrespect of the current legal order.”

“If the lawyer is so committed to the ending or prevention of abortion that he ends up harassing and intimidating people who are engaging in legal conduct, it does raise the question of whether he will be able to provide independent judgment,” Clark says. “If HHS or ORR acted unlawfully in a way that was consistent with his anti-abortion ideology, would he advise them of that? Would he even be able to recognize it? Or is his commitment on this particular issue so strong that it would interfere with his ability to present independent professional judgment to his client?”

While it’s been 17 years since Bowman’s last recorded run-in with the law, he hasn’t fully left his activist past behind. This past August, Bowman and his family joined a birthday party for Will Goodman—Bowman’s old buddy from his Wisconsin clinic-protesting days—in Washington, DC. In the nearly 20 years since his protests with Bowman, Goodman has remained a fixture in grassroots anti-abortion activism. He’s been arrested as recently as July and served jail time for various protest actions, including several “Red Rose Rescues” where he entered clinic waiting rooms without permission to give patients flowers and literature promising to help them if they give birth.

Goodman had gotten out of jail just six weeks before his party, having completed a 45-day sentence after violating his probation by again entering a clinic to minister to patients. Two weeks after Bowman and his family celebrated with Goodman, he was again arrested at a Washington, DC, clinic while taking part in a Red Rose Rescue.

This article has been updated.

Photo credits: David Duprey/AP; Alliance Defending Freedom/Vimeo