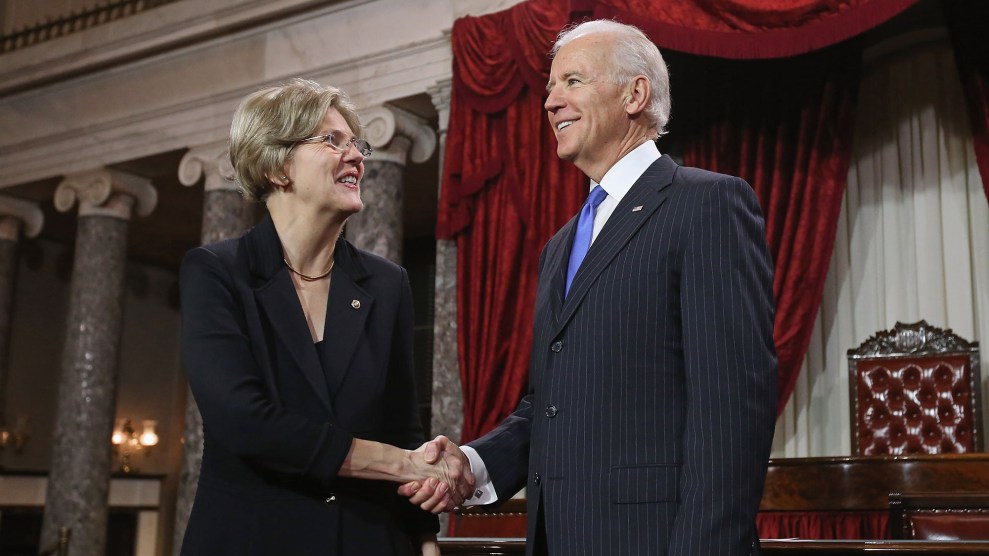

Chip Somodevilla/Getty

Joe Biden was outraged. In February 2005, after eight years of starts and stops, the Senate was finally moving forward on a landmark overhaul of the nation’s bankruptcy laws—a bipartisan behemoth piece of legislation, backed by big banks and credit card companies, that the Delaware senator had taken a lead role in shepherding. But at the Senate Judiciary Committee’s public hearing on the bill, one of the witnesses had said something about his home state that Biden couldn’t let stand.

The witness’ specific concern was Delaware’s unique status as the venue of choice for large corporations filing for bankruptcy. Companies understood that the courts there (where many of the companies were nominally incorporated) were more likely to take their side against creditors, such as employee pension plans. And the venue-shopping opened up a broader issue of access; massive companies such as Enron could choose a forum thousands of miles away from where their employees lived, effectively shutting the workers out of the process. The Delaware option allowed companies to “escape the obligation to make the process open,” the witness said, while the millions of individuals filing for personal bankruptcy every year had no such luxury.

“I find the language that is used kind of fascinating—‘escape from the obligation to be open,’” Biden said in response. Was this witness suggesting “that the Delaware chancery court is not open, is somehow an unfair court? I find it outrageous, such a statement.”

“Maybe you can tell me,” he asked. “Is it not a competent court? Is it not an open court?”

Elizabeth Warren, the Harvard Law School bankruptcy professor who had been testifying vigorously against the bill for more than an hour, replied, “Are you asking me, senator?”

“Well, yes,” Biden said. “You are the one that said ‘escape the obligation of making the process open.’”

“Actually, senator, bankruptcy cases are not heard in Delaware chancery court.”

Biden quickly corrected himself—bankruptcy cases are heard in bankruptcy court—but the exchange was emblematic of things to come. For the next 14 minutes, running well over Biden’s allotted time for questioning, he and Warren debated the role of government in a way that felt personal.

It was not the first time the pair had clashed, and it wouldn’t be the last. Long before their Capitol Hill clash, Warren called out Biden by name in op-eds and in her first book, accusing him of carrying water for the big corporations that called his state home and kept his campaign coffers full.

The bankruptcy fight was a pivotal moment for both Warren and Biden, who have each built a political brand based on a defense of the American middle class. Biden is fond of saying that he talks about working families so often his colleagues called him “Middle-Class Joe.” (Exactly who has ever called him that is a mystery.) Warren’s 2017 book was subtitled “The Battle to Save America’s Middle Class.” But there’s a key difference. In Warren’s telling, politicians like Joe Biden are exactly who the middle class needs protection from. And as the 2020 Democratic presidential campaign slowly heats up, the two may be on a collision course once more.

The primary point of conflict between Warren and Biden has been bankruptcy reform, which was accomplished with Biden’s 2005 bill. Though the law was enormously complex, its most important consequence was simple—the legislation made it harder for millions of Americans who had fallen into debt and who sought relief through bankruptcy to break free from their obligations. At the same time, the bill entitled creditors, such as car companies or mortgage lenders, to an even greater share of their assets.

Warren, whose research at Harvard focused on the causes of individual bankruptcy, had allies in her fight against Biden’s bill. Women’s groups, including the National Organization for Women’s Legal Defense and Education Fund, opposed the measure because of the disparate impact it would have on women, who made up a rapidly increasing percentage of all personal bankruptcy filings. The legislation also made it harder for single mothers to collect child support from bankrupt exes, by strengthening protections for other creditors.

Some of the same women’s groups that were fighting the bill had previously elevated the Delaware senator to exalted status because of his work passing the Violence Against Women Act. And that’s what made Biden’s support for the measure so grating to Warren.

Warren first began publicly taking on Biden in 2002, when she wrote a paper for the Harvard Women’s Law Journal suggesting that his position on bankruptcy had been effectively bought.

“His energetic work on behalf of the credit card companies has earned him the affection of the banking industry and protected him from any well-funded challengers for his Senate seat,” she wrote. With a touch of snark, she added, “This important part of Senator Biden’s legislative work also appears to be missing from his Web site and publicity releases.”

And in a New York Times op-ed that year she called the bankruptcy bill “unconscionable,” singling out Biden for his work on it. “Apparently many politicians believe they can remove the last safety net for families facing financial disaster (many of which are led by women) so long as they can find another highly visible issue that lets them proclaim their support for women,” she wrote.

She took on Biden again in The Two-Income Trap: Why Middle-Class Mothers & Fathers Are Going Broke, the best-selling 2003 book she co-authored with her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi. “Women’s issues are not just about childbearing or domestic violence,” they wrote. “More women with children will search for a bankruptcy lawyer than will seek subsidized day care. And in a statistic with special significance for Senator Biden, more women will be victimized by predatory lenders than will seek protection from an abusive husband or boyfriend.”

Warren and Tyagi continued, “The point is not to discredit other worthy causes or to pit one disadvantaged group against another. Nor would we suggest that battered women deserve less help or that subsidized day care is unimportant. The point is simply that family economics should not be left to giant corporations and paid lobbyists, and senators like Joe Biden should not be allowed to sell out women in the morning and be heralded as their friend in the evening.”

So by the time they faced off at the Hart Senate Office Building in February 2005, Warren had been attacking Biden for years. After the initial affaire d’honneur over Delaware’s court system, Biden laid out his philosophical objection to Warren’s central criticism. If Americans really were drowning in debt for excusable and troubling reasons—the fraying of the social safety net, a broken health care system, predatory lending—as Warren believed, then perhaps what she should really be advocating was for the government to foot the bill—and not leave the creditors hanging.

“We are going to ask the gas company, the drugstore, the automobile dealer to pay for the broken system instead of having the nerve to come and say it is a moral obligation of a nation to pay for that broken system,” he said.

Warren—citing the example of a woman who had borrowed $2,200 from a lender and paid back $2,100 but, because of high interest rates, still owed $2,600 at the time of her bankruptcy—responded that some companies had made more than their share. And this exchange followed.

BIDEN: Maybe we should talk about usury rates, then. Maybe that is what we should be talking about, not bankruptcy.

WARREN: Senator, I will be the first. Invite me.

BIDEN: I know you will, but let’s call a spade a spade. Your problem with credit card companies is usury rates from your position. It is not about the bankruptcy bill.

WARREN: But, senator, if you are not going to fix that problem, you can’t take away the last shred of protection from these families.

BIDEN: I got it, okay. You are very good, professor.

And scene.

A few months later, Biden responded to the criticism of Warren and others—although he did not mention her by name—in a Senate speech. The bill, he argued, actually strengthened protections for recipients of child support. Child support and alimony payments would move up in the pecking order relative to some other claims, such as administrative fees.

“I wish that those who are fabricating wild claims about [the bill] would stop,” he said. “If they have their way, the women and children in this country who depend on alimony and child support will be robbed of real protections. That would be a crime.”

But Charles Tabb, a professor of bankruptcy law at the University of Illinois, says Warren’s criticisms were “absolutely on point.” Biden and his allies made a series of small, mostly cosmetic changes to the law that allowed them to boast that the law they passed made the payment and collection of child support and alimony easier. The law ensured that such payments would take priority over administrative costs associated with the bankruptcy. But by increasing the amount of money that auto loan companies, or major appliance retailers like Sears, could skim off the top in the form of liens against people in bankruptcy, the bill effectively shrank the pot of money from which debtors could pay off everyone else.

“It’s a zero-sum game,” Tabb says. “If a debtor wanted to keep the fridge and pay child support, they [now] have to pay more to keep the fridge. There are a number of provisions like that, where various secured creditors get more. That has to come off the back of somebody, and it’s got to be somebody that doesn’t have a lien. And child support payments don’t have a lien. You’ve got to pay all the liens first.”

The National Women’s Law Center, in a letter to senators at the time, called the changes championed by Biden “virtually meaningless.”

For Warren, her first foray into the political arena proved to be a formative one. “The bankruptcy wars changed me forever,” she wrote in her 2014 memoir, A Fighting Chance—a book that once more dragged Biden for his role in the legislation. “Even before this grinding battle, I had begun to understand the terrible squeeze on the middle class. But it was this fight that showed me how badly the playing field was tilted and taught me that the squeeze wasn’t accidental.”

The bankruptcy fight also cemented Warren’s status as a public intellectual in progressive politics. Just a few years later, she was back in Washington as director of the Congressional Oversight Panel for the Troubled Asset Relief Program (the Wall Street bailout), and not long after that she was helping turn her proposal for a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau into law.

By then, Biden’s own political leanings had shifted. As vice president, he helped push through the 2009 Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, which implemented new regulations on the financial-services industry, and he backed Warren’s CFPB as it got off the ground.

“I think Biden in 2005 was pretty different in this space than he was in 2009—he’s really different,” says Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities who served as the vice president’s chief economist during the financial crisis. “In 2005, he’s a senator from Delaware, where so many companies are incorporated, [and] the extent to which financial services were screwing around with consumers wasn’t nearly as clear then as it was a few years later. I think his views on this pretty clearly evolved when he became vice president after the housing bubble exploded, at which point he became a strong advocate of consumer protections and regulating financial services.”

But the essential conflict between Biden and Warren lingered. In a 2015 interview with Yahoo News, Biden characterized now-Sen. Warren’s overall policy preference as “punishing the rich,” while he sought to hammer out compromises with credit card companies. He boasted of the administration’s 2009 passage of the CARD Act, a credit card holders’ bill of rights. “If you look at Elizabeth Warren’s argument on this: ‘You should have just shut the suckers down,’” he said. (Warren actually supported the CARD Act, and the Warren quote Biden was referring to—“We permit credit products to pass every day in commerce in America that if they were toasters, we would shut those folks down”—was Warren’s main argument for the CFPB, which Biden backed.)

Biden wasn’t the only leading Democrat whom Warren took to task in her books. In A Fighting Chance, she described meeting with then-first lady Hillary Clinton in 1998 to make the case against an earlier iteration of a bankruptcy bill. Clinton, in Warren’s telling, left the meeting determined to help defeat it. But when Clinton joined the Senate, she eventually voted for bankruptcy reform. “The bill was essentially the same, but Hillary Rodham Clinton was not,” Warren wrote. “Big banks were now part of Senator Clinton’s constituency. She wanted their support, and they wanted hers.”

Warren lost what she called the “bankruptcy wars.” But now, she is banking on that message she pushed unsuccessfully in the 2000s resonating with Democratic voters. When she kicked off her campaign for president in Iowa in January, she voiced a critique of money in politics that had its roots in her earlier crusade. But on that first campaign swing, the subject of bankruptcy came up only once, when a voter in Des Moines thanked her for a bill she introduced last year that aimed to roll back portions of the Biden-era law. “It’s a nerd thing,” Warren said to some laughs. “But it really matters to families in trouble and to small businesses in trouble.”

Biden is not yet in the 2020 race. But if he leaps into the ever-growing fray, these two self-proclaimed champions of the middle class could find themselves competing for the same set of voters. It’s possible this old feud over a piece of economic policy that few voters ever paid close attention to could be revived. And if it does come up, there’s little doubt about which candidate sees their role in the fight as an asset. Warren devotes ample space in her books to her unsuccessful fight against Biden and his bill. But in his two books, Biden never mentions the years he devoted to winning this fight—and beating Warren.