Joe Mahoney/Getty

The past two-plus years have been a ride. President Donald Trump’s tenure so far has been peppered with such a range of awkward, upsetting, disturbing, and downright horrifying moments: from talk of grabbing pussies to “covfefe” to the paper towel tossing in Puerto Rico to calling former porn star Stormy Daniels “Horseface” to the endless “WITCH HUNT!” rants on Twitter.

It often feels like too much to keep up with and remember. But now, researchers from Michigan State, the University of Lübeck in Germany, and the University of Frankfurt have actually mapped these lowlights, at least indirectly. In a study published Wednesday in the journal Frontiers in Communication, they measured the country’s embarrassment levels, according to Twitter posts in the United States, starting when Trump announced his presidential campaign.

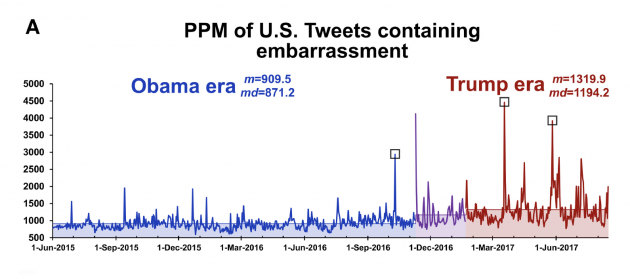

After identifying 20 million posts related to embarrassment—that is, tweets containing “embarrassment,” “embarrassed,” or “embarrassing”—between June 2015 and August 2017, the researchers found that large spikes in mentions of the words corresponded with various events in Trump’s political rise and presidency. They found that even the spikes in President Obama’s final year were still coordinated with Trump moves.

In chronological order, peak embarrassment on Twitter correlated with:

1. The second presidential debate on October 9, 2016, during which Trump promised, if he was elected, to imprison Clinton

2. The November 8, 2016, presidential election

3. The time in late November 2016 when Trump claimed “millions of people” voted illegally

4. Trump’s January 2017 inauguration

5. The time Trump denied the handshake of German Chancellor Angela Merkel in March 2017

6. Trump’s decision to drop the “mother of all bombs” on Afghanistan in April 2017

7. The time Trump appeared to shove Montenegro Prime Minister Duško Marković at a NATO meeting in May 2017

8. Trump’s June 2017 announcement that he plans to withdraw from the Paris agreement

9. Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s seemingly cozy meeting at the G20 summit in July 2017

10. Trump now infamous statements regarding the Charlottesville rally—and a lack of condemnation of white supremacy—in August 2017

(Due to resource limitations, the researchers couldn’t examine tweets in 2018 or 2019. )

“Peaks in embarrassment expressed on U.S. Twitter labeled with events and actions taken by Trump within the preceding days.”

Frontiers in Communication

Lead author Frieder Paulus, an assistant professor for social neuroscience methods at the University of Lübeck, tells Mother Jones he and his colleagues have spent years studying embarrassment, including the type of embarrassment people feel for others outside their family. Recent polls suggest that Trump’s performance as president has been embarrassing for Americans, but the researchers, according to the study, wanted to “provide further evidence linking Donald Trump to nationwide communication of embarrassment.”

So, they went to Twitter. Once they had found all the instances of people tweeting about embarrassment, they noticed ten spikes. But, without looking at the content of the tweets, it wasn’t yet clear if the spikes were truly about the president. “We thought, well, is this really related to Trump or just a coincidence?” Paulus says. So for the top three spikes, they pulled the words co-mentioned with embarrassment, which added up to about 40,000 tweets for each day. They found that words like “debate” appeared around October 9, 2016; “Merkel” around March 18, 2017; and “NATO” around May 25, 2017. It then appeared Trump’s actions were in fact related to the spikes, Paulus says.

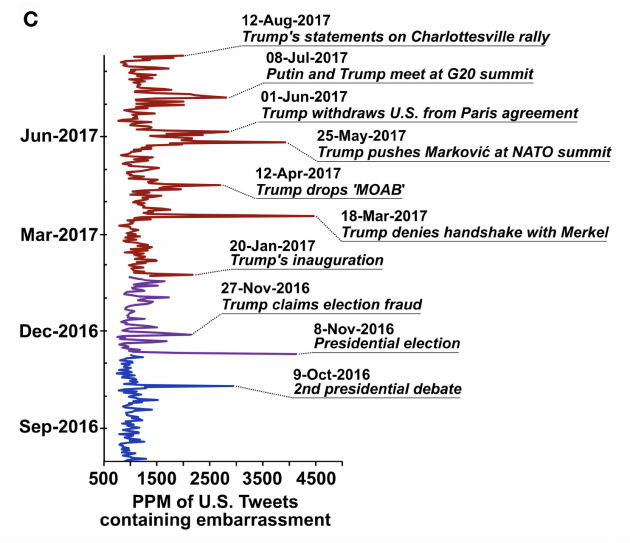

Overall, they discovered that from the time Trump took office in January 2017 to August 2017 (in red, below), the average proportion of tweets referring to embarrassment has increased by an astounding 45 percent compared to the last year of Obama’s presidency before Trump was elected (in blue, below).

“There’s a clear increase [in tweets related to embarrassment] with the time when Donald Trump was elected—you can see it in the figure,” Paulus says. “With Obama, there’s not much going on, but then you have clear cut, and you have an increase in how much people talk about embarrassment.”

Mentions of embarrassment of Twitter (parts per million) between June 1, 2015, and August 13, 2017.

Frontiers in Communication

A main constraint of the initial findings, the authors write, is that they only show that Trump’s actions correlated with embarrassment on Twitter. Without further statistical analysis, it’d be difficult to argue that Trump’s political blunders really had anything directly to do with embarrassment. To further solidify their findings, the researchers also calculated what people were feeling (or said they were feeling) when they directly mentioned the president, or at least his Twitter handle (@realDonaldTrump). They considered tweets mentioning expressions of embarrassment, shame, disgust, and anger—but also pride and happiness—between June 2015 and December 2017.

They found that “the more people talk about embarrassment,” Paulus says, “the more likely it is that Donald Trump is also included in that tweet.” The same trend was true of disgust, shame, and anger—but not pride or happiness. In fact, on days when a lot of people were tweeting about happiness, the probability of Trump being mentioned was lower than on days when few people were tweeting about happiness.

As the authors note, there are still several limitations of this study, the largest of which is, according to Paulus, the unreliability of Twitter data itself. Twitter is not a random sample of the US population and some of the tweets indicating embarrassment may have been sarcastic, inauthentic, or even coming from bots (although, it is “unlikely” that bots systematically targeted embarrassment on Twitter, according to the authors). “The validity of each Twitter post we analyzed is impossible to verify,” the authors write.

Bryor Snefjella, a Ph.D. student at McMaster University and author of a similar study which found Canadians are disproportionately polite on Twitter and was not involved with the Trump study, tells Mother Jones the new study was “well done,” but also said looking into the effect world leaders other than Trump have on embarrassment may make the findings more robust, if only by offering a base level of comparison. And, echoing Paulus, Snefjella says it’s important to keep in mind that just because someone is tweeting about embarrassment, it doesn’t mean that’s what they’re actually feeling—or that it was directly caused by Trump. “It’s generally quite challenging to really come up with causal evidence with this kind of data,” he says.

Either way, Trump may want to take note of how his actions are playing out on his favorite social media platform, especially ahead of the 2020 election. Nation-wide embarrassment may impact voter choice and other political action, Paulus says. “If you feel strong emotions, and embarrassment can be a strong emotion, but also anger or disgust, people might get motivated to do something politically.”