On a spring morning in 2017, in a Grand Hyatt ballroom in midtown Manhattan, Michael Cartwright took the stage and talked about growth. “There’s no great brand out there—Nike, whatever you consider a great brand out there today—that doesn’t have a great sales and marketing platform,” he told the audience of health care investors and executives attending a UBS-sponsored confab. That’s why, Cartwright said, his company—American Addiction Centers, the nation’s only publicly traded addiction treatment chain—had built a thriving marketing machine.

And it was vast. Some 65 sales reps marketed AAC’s services to therapists, DUI attorneys, and doctors. The company operated more than 100 websites, ensuring AAC showed up frequently in search results. “If you type in ‘heroin addiction’ or ‘methamphetamine addiction,’” Cartwright, AAC’s CEO, told his audience, “you’re probably going to come across one of our websites.” Each month, roughly 30,000 calls came in to AAC’s call center in Nashville, where, he said, “we have 100 sales reps answering the phone every day.” AAC had dozens of facilities across eight states, including high-end residential centers, outpatient programs, and sober-living housing. According to Cartwright’s slides, the average residential client brought in more than $22,000 in revenue.

RELATED: How rehab recruiters are luring recovering opioid addicts into a deadly cycle

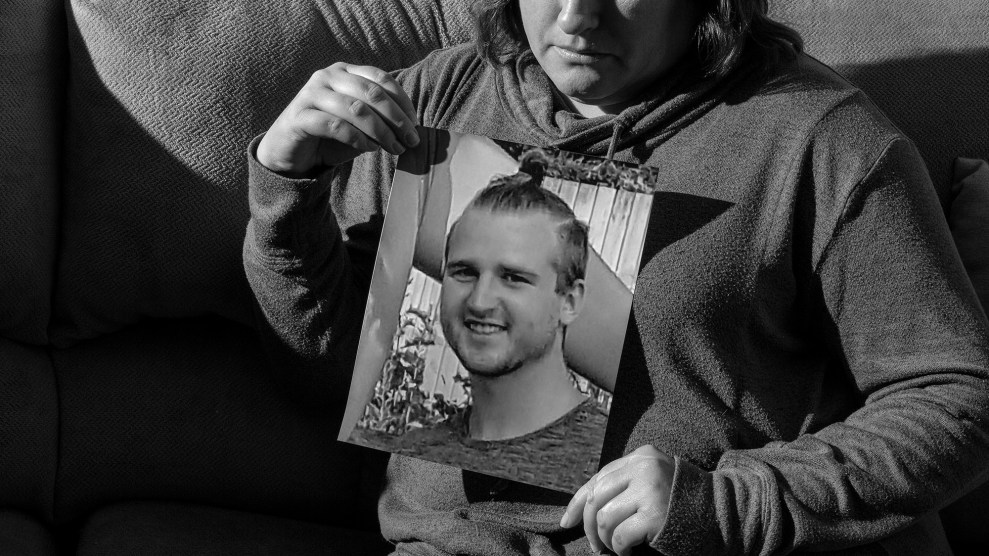

Two months after Cartwright’s presentation, on a scorching Friday morning a few miles from the Las Vegas Strip, 23-year-old Cody Arbuckle was found unresponsive in his room at Solutions, an AAC-owned “therapeutic recovery home.” Staffers were supposed to closely monitor patients in the throes of drug and alcohol withdrawal—a brutal process that can include vomiting, shaking, and seizing. But Arbuckle was left unattended for several hours, according to a police report and a subsequent lawsuit. A coroner concluded that Arbuckle overdosed on Imodium, an over-the-counter antidiarrheal that can cause a high in large doses.

A lack of supervision at Solutions facilities was not abnormal, according to three former nurses who worked at the program’s various recovery homes in Las Vegas. “Behavioral health technicians,” often recovering drug users themselves, were supposed to supervise residents while a nurse treated individuals. But the techs were often occupied by other tasks—picking up clients from the airport, driving them to other facilities, watching television, or browsing the internet. In an email to his supervisor last summer, nurse Greg Houck noted that the sole tech at the Solutions where he worked kept leaving to pick up clients. “I have a full house,” Houck, who was laid off a few months later, wrote to his manager. “What if someone gets hurt? Once again, a safety issue.” What’s more, some houses didn’t have basic medical emergency equipment, like oxygen tanks and injectable anti-seizure medications. “It was just a free-for-all, do your own thing,” one nurse told me. “And the patients are the ones who get cut short.”

Over the past five months, Mother Jones interviewed several former AAC employees and combed through years of investor calls, federal filings, and police reports. We found that Arbuckle’s death is just one of multiple in recent years at AAC’s Las Vegas facilities, which house about a fifth of the company’s roughly 1,500 beds. There was Connor Johnson, a 25-year-old from Connecticut who allegedly told AAC staff that he was suicidal but, according to a lawsuit, hanged himself in late 2016 with a belt. There was Joseph N., also 25, who didn’t wake up one February morning last year when a staff member came to his room at 6 a.m. with a message to call his mom. According to a police report, the staffer told Joseph’s roommate to relay the message and left; 15 minutes later, the roommate realized Joseph wasn’t breathing. Then, last September, 33-year-old April Leeming was found dead at Desert Hope, AAC’s sprawling Las Vegas inpatient treatment center. She was allegedly unmonitored for nearly nine hours, according to a police report, even though she had arrived just a day before and had a history of seizures.

Together, the deaths in Las Vegas, interviews with former employees, and lawsuits against AAC paint a disquieting portrait of a company that failed certain vulnerable patients as it reaped millions.

Cody Arbuckle shortly before he died

Courtesy of the family

AAC has disputed the allegations that patients are routinely unsupervised, as well as the allegations detailed in the Johnson and Arbuckle lawsuits. “We see more patients than any other peer treatment provider and our safety record speaks for itself,” a spokesperson told me, adding that he could not comment on individual cases due to patient privacy. The company maintains that there is one patient death for every 4,274 discharges from AAC facilities—a rate 10 times lower than the industry average. However, it declined to provide data on how many AAC patients had died and how many had been discharged. The spokesperson also noted that staff members are required to report safety issues, like the ones detailed by Houck and others, and that such concerns “were never reported to our corporate compliance office, which would have ensured a swift and appropriate response.” Regarding the specific scenario Houck described in his email, the spokesperson said, “We looked into this situation and found that there were no violations of our policies.”

For his part, Cartwright claimed the allegations that patients were left unsupervised are “a lie.” He also suggested that lawsuits against the company were fueled by lawyers seeking a profit, as well as short sellers betting against the company.

To be sure, AAC’s visibility has increased since its $75 million IPO in 2014, garnering big-name investors like Morgan Stanley and Deerfield Management. Its growth offers a rare window into an industry that has become red-hot as the opioid epidemic has boomed. The rehab landscape is populated by small, mom-and-pop facilities, with the average treatment center serving fewer than 100 patients. Often, the basic rules of medicine don’t apply to addiction treatment—many rehabs don’t employ a single licensed doctor—and while prospective patients can compare performance data from hospitals and nursing homes on Medicare.gov, no such database exists for rehabs. It’s nearly impossible for the average recovering user or desperate parent to tell which facilities offer ethical, evidence-based care.

Amid the patchwork of treatment options, AAC aimed “to build a national brand that can truly help be part of the process of curing the disease of addiction,” as Cartwright put it at the UBS conference. In earnings calls and investor presentations, AAC’s executives talk about addiction and recovery, but also about generating leads, increasing conversion rates, and filling beds. “Our goal now is to increase the utilization of our beds, improving collections in reducing overhead and facility costs,” said then-Chief Financial Officer Kirk Manz at a health care conference in the spring of 2017. “We look at cost per channel, cost per call, conversion rates, whether or not an ad on the Fox network outperforms an ad on CNN—all those kinds of things that we do to try to drill down to continually push our customer acquisition costs to the lowest it possibly can be.”

He concluded, “We are a health care company, but we are also a consumer marketing company.”

Such language may seem indelicate for an industry that treats a vulnerable population struggling with addiction. But rehab representatives argue that treatment centers need to market themselves for patients to find their care. After all, advertising is normal in health care: TV viewers don’t bat an eye at commercials pitching hospitals or prescription drugs. As AAC leads the rehab world in becoming more like the rest of the health care industry, it has to grapple with new questions: What does it mean when treating addiction is big business? And if rehabs answer to investors, will patients suffer?

“There is nothing wrong with profitable business,” said Marvin Ventrell, executive director of the National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, the industry’s main trade group, about the rehab field as a whole. “The problem,” he added, “arises where profit goals dictate treatment services.”

In December, I flew to Las Vegas to meet Michael Cartwright at Desert Hope, the facility where April Leeming had been found dead three months earlier. The campus, which can house nearly 150 patients, feels like a cross between a hotel and a hospital. Visitors are greeted with dark wood floors, plush sofas, and a fireplace in the lobby. Christmas decorations lined the walls. Upstairs, nurse’s stations were nestled among the residents’ rooms, each bed outfitted with a device that tracks vital signs as patients sleep. There’s a cafeteria, a gym, and a massage room. It’s easy to see why someone would want to send a loved one here.

A few weeks earlier, I had sent AAC a long list of questions about its care and track record. Within two days I had received both a threatening letter from the company’s lawyer and a friendly invitation from its PR rep to sit down with Cartwright. He flew across the country from AAC’s Brentwood, Tennessee headquarters to meet me. Wearing a blazer and Nike AAC-branded cap, the CEO, 50, spent several hours with me, often describing critiques of the company as “odd” or “interesting” in his slight Tennessee twang, blue eyes unwavering. He alternated between perceptive, empathetic opinions on addiction and blustery defensiveness that at one point prompted his PR rep to confirm whether he really intended to speak on the record.

Not only were allegations that patients were routinely left alone in Solutions detox houses “a lie,” but the witnesses who gave testimony in a high-profile lawsuit against AAC were “absolutely, 100 percent lying.” The family members of Shaun Reyna, who were awarded $7 million in damages after Reyna died at an AAC facility in 2013, had been “phished to sue.” The former AAC employees who had spoken to me were “whoever the lawyers have paid a $10,000 check.” (Of the recent AAC employees I interviewed, Houck was the only witness in a lawsuit; he denies receiving any compensation for his participation.)

Even so, moments after such comments, Cartwright was conciliatory, urging me to give his cell number to any employee who might have observed problems. “I’ll talk to them,” he said. “I’ll go meet with them for coffee and say, ‘Please. Tell me what we did wrong. How can we improve?’” What happens at AAC facilities is personal for Cartwright. “This is my company,” he said slowly at one point, eyes narrowing into a squint. “This permeates me. This permeates my DNA.”

In his youth, Cartwright struggled with psychiatric problems and addiction. As a sober adult, he marveled at how few rehabs treated both mental health and substance use, and in 1995, he and his wife founded a Nashville nonprofit treatment center specializing in dual mental health and addiction diagnoses. “Believe it or not, in 1995, there was a total of three books and 50 journal articles—and that’s it—on the topic of dual diagnosis,” he claimed. “It did not take me long to become an expert because I read every one of them. I read all three books and all 50 journal articles and therefore I was the most knowledgeable person to do that.” Four years later, Cartwright founded Foundations Recovery Network, a private treatment chain that he led until 2009.

Then in 2011, Cartwright co-founded American Addiction Centers. The company grew quickly, boasting $28 million in sales within a year. Just three years later, in 2014, Cartwright rang the bell on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange to announce AAC’s initial public offering, making it the first health care provider solely focused on addiction to go public.

Michael Cartwright, accompanied by his daughter, on the day of AAC’s initial public offering

Richard Drew / AP

The decision to IPO, Cartwright has said, was inspired not necessarily by profit, but by the need for standardized care. “Many times, these treatment centers are in homes, they’re in apartment buildings,” he said in a Bloomberg video profile in 2015. “I think what you’ll see over the next 20 years is…much more professionalized, hospital-style campuses, much nicer facilities. How do you do that? You need capital.”

Money has been pouring in to the rehab field, thanks to the spiraling opioid epidemic and laws implemented in the past decade requiring insurers to cover addiction treatment, including the Affordable Care Act. From 2011 to 2015, private insurance spending on patients with opioid addiction diagnoses multiplied tenfold, to $722 million, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit that tracks insurance claims. Mergers and acquisitions related to drug and alcohol addiction programs doubled between 2013 and 2016, according to the Braff Group, which advises investors on health care stocks. With more people heading to rehab and more money to pay for it, said president Dexter Braff, “the investment community noticed.”

Money is pouring in to addiction treatment.

Private insurance claims for opioid users (millions of dollars)

And for-profit providers are increasing their market share.

Rehab attendance (thousands)

AAC’s growth hasn’t been linear. The company’s stock went into free fall in 2015 after California prosecutors indicted company subsidiaries with murder for a 2010 death at a facility acquired by AAC. The charges were later dismissed; a coroner’s report found that the patient died of heart disease. In 2016, AAC agreed to independent monitoring of its operations in California and to pay the state a $200,000 civil penalty.

Still, by 2016, AAC’s revenue had soared to $280 million. For years, a significant portion of its revenue came from diagnostic testing: AAC also owns Addiction Labs of America, which tests patient urine for drugs, among a host of other lab tests. In 2017, AAC announced the acquisition of AdCare, a treatment chain primarily serving Medicare patients in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Today, AAC has nine inpatient centers, 15 outpatient locations, and four sober-living facilities. The business has paid off for Cartwright, who made $1.3 million in 2017.

The average residential patient brings in roughly $800 per day in revenue for AAC, most of it paid by private insurance. Cartwright acknowledged to Mother Jones that AAC’s rate is far higher than those of publicly funded facilities but said it’s on par with other private providers. “The type of clientele that we have—usually upper-middle class families throughout the United States—they’re expecting a nice facility, nice amenities, laundry service, good food [and] client-staff ratio,” he said.

Many patients first interact with AAC through the company’s websites, which include Recovery.org and Rehabs.com. Until recently, it was easy to mistake the websites for independent, informational referral portals; only if you clicked on the “Who Answers?” link next to a hotline number would you learn that the lines were answered by AAC representatives. Last summer, members of a US House of Representatives subcommittee investigating the rehab industry pressed Cartwright on the transparency of the websites. “We were the only ones criticized about it, which I think is quite odd,” Cartwright told me, adding that AAC’s competitors have similar sites “and none of those websites are transparent and clear.” Today, AAC’s sites are clearly labeled as “An American Addiction Centers Resource.”

If someone calls the hotline number, they’re connected with one of AAC’s many call center employees. Between 250 and 300 of the company’s 2,000 employees were dedicated to generating or answering calls in 2017, said then-CFO Kirk Manz at a health care conference. Hotline staffers, who were paid on commission until last summer, sometimes made promises that weren’t kept, according to the Arbuckle lawsuit. “The representative told me they provided medically supervised detox by a doctor on staff,” alleged Daniel Baer, a former Solutions patient in Las Vegas who submitted a declaration for the case. “They told me they have a pool and equine therapy. They told me they had four-star chefs.” Ultimately, Baer said, “I never saw a doctor during the entire time I was in the program.” (AAC lawyers called Baer’s comments a “parade of irrelevant evidence aimed at smearing” the company; a company spokesperson added that call center employees are trained for a month before taking calls and sometimes refer patients to other rehab programs.)

Cartwright made a point to acknowledge in our conversation that he may have referred to the call center operators as salespeople in the past, but he doesn’t think of them as salespeople. He prefers to call them “navigators.”

Kryss M., a 23-year-old Las Vegas native, is like a walking, talking promotion for AAC. Company executives suggested that I connect with him, and I can see why: He speaks earnestly and openly about his recovery—he, in fact, often talks about it on panels at AAC facilities—and he credits the company with turning his life around.

Last year, Kryss hit rock bottom. He and his wife were quarreling over his heroin addiction and she wouldn’t leave him alone with their two-year-old daughter, afraid he would nod off. After trying and failing to quit on his own, Kryss checked himself into Desert Hope. Shortly after he got out, he relapsed and checked himself in again, this time with Solutions. The programs “made me go from the hole that I was in, where I didn’t care about anything or anybody—and I rather would have died the next shot I did or the next hit I took—to being happy,” he told me. “Genuinely happy. To want to live. To want to wake up every day.” Today, he lives with his wife and daughter and attends recovery meetings daily. This summer, he’ll start working conventions on the Strip.

Stories abound of former AAC patients like Kryss, said Cartwright—and he claimed staffers regularly receive letters and emails from former patients and their relatives. When we met, Cartwright handed me a printed stack of them, 15 pages long. They include messages like, “Thank you for giving me my wife back”; “You are a blessing to have known”; and “I can see the light at the end of the tunnel, and it looks sober and bright and beautiful.”

It can be difficult to square these hopeful, redemptive stories with the allegations from former employees and lawsuits depicting seemingly preventable deaths. After all, Kryss was at Desert Hope around the same time that April Leeming died, and at Solutions around the same time that Houck, the former nurse, said he was trying to sound alarm bells about the lack of supervision. “The patients are not really safe when these guys are on,” Houck wrote in another email to his manager in regard some behavioral health technicians. “I just walked through the living room on my way back in from escorting a patient to the car…and I noticed [a patient] was not breathing. I stopped to assess, watching her closely, and over my shoulder the tech asserts ‘She’s ok, she’s breathing’ and as I stood there the patient was apneic [not breathing] for > 30 seconds.”

An AAC spokesperson noted, “Giving and receiving addiction treatment is tough and sensitive work, and while sometimes tragic and heartbreaking, AAC is proud of its safety record.” The company reviewed its records and “does not believe [the incident in Houck’s email] occurred as described,” he said, adding that protocol requires employees in this situation to call 911. “If a staff concern has merit, it is handled appropriately and swiftly,” the spokesperson concluded.

The reality is that AAC treats thousands of patients with varying needs each year across dozens of facilities, which themselves vary greatly—from large residential campuses like Desert Hope to independent sober-living apartments, where patients typically live as they attend outpatient treatment.

Just a few miles from the gleaming Desert Hope campus is Resolutions, a hotel-turned-AAC sober-living apartment complex in the rundown outskirts of the Strip. It was at Resolutions that a roommate discovered Joseph N. was not breathing, according to a police report. Homeless encampments line nearby blocks. Across the street is NuWu Cannabis Marketplace, which proudly advertises itself as the “largest recreational cannabis store on the planet”—open 24 hours and featuring a drive-thru. “That area of town, you have dope dealers right across the street,” one former AAC nurse told me. When I asked Cartwright about the prevalence of drugs in neighborhoods housing some AAC facilities, he said, “I could take you to any block in America and we could sniff out drugs in about 15 minutes.”

In an email, Thomas Doub, AAC’s clinical and compliance officer, acknowledged that scaling up has not always been easy: “Along with rapid growth and scale come challenges of integration, particularly with facilities that we acquire,” he wrote. “Those facilities often bring exceptional best practices that benefit the entire company, but sometimes need work in certain areas to meet AAC quality standards.”

Still, AAC executives claim the company’s methods are highly effective. A study commissioned by AAC and published last February included more than 4,000 patients and found that 63 percent were drug-free a year after treatment. This was notable: Individual rehabs rarely share data on patient outcomes, in part because relapse is incredibly common. By some estimates, four in five opioid users turn back to drugs within one year of detoxing. Cartwright called the study’s findings “very gratifying” in an earnings call last year, adding that “delivering excellent clinical care remains our top focus and it is clear that our approach is having a real impact.”

A closer look at the study, however, reveals that the reality is more complicated. The 63 percent figure comes from 168 patients who were randomly chosen from the original 4,000 patient cohort. Only 81 responded and had completed AAC treatment. Of those 81 clients who were reached one year after treatment, 63 percent self-reported being abstinent—for the past month. If some of those who didn’t respond had in fact relapsed, AAC’s outcomes may have changed significantly. The study also fails to disclose that the organization conducting the study, the Centerstone Research Institute, was run by Doub, who left to work for AAC midway through the research. In an email, Doub said that measures were taken to ensure the result was meaningful for a larger population, noting, “No other addiction provider has been nearly as transparent with their outcomes methodology or findings.” He said his direct involvement in the study while he was at Centerstone was minimal and that AAC had no influence on the findings.

When I asked Harvard health economist Richard Frank for his opinion, he concluded that “one can’t know with any confidence from this study” how AAC is doing in terms of outcomes. There is, he said, “much to be skeptical about.”

AAC’s stock again plummeted this past November, losing nearly half of its value after executives lowered projected annual revenues in an earnings call. The problem stemmed largely from a marketing issue. Google tweaked its algorithm last summer in a way that dramatically reduced the visibility of many health care and rehab websites, and the change was devastating for the company: Between July and September, AAC saw a 30 percent drop in calls to the hotline and a 10 percent decline in the number of clients at facilities. “We got hit by a little bit of a meteorite,” CFO Andrew McWilliams told investors in November. In a quarterly report released the same day, AAC acknowledged it was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission relating to “accounting for partial payments from insurance companies.” The investigation is “neither an allegation of wrongdoing nor a finding that any violation of law has occurred,” said AAC’s report.

A month later, the company announced a cost reduction initiative, laying off some 200 employees. It has since consolidated operations in Las Vegas, merging all Solutions operations into Desert Hope, and sold its facilities in Louisiana. “We fully realize that our recent performance was unacceptable,” Cartwright said in a statement. “We have made significant investments in a corporate infrastructure meant to support a larger business than we have today and that is why we are taking action to streamline the organization.” Moody’s Investor Service also concluded in December that there is a possibility that AAC will default on its debt. Days later, AAC announced a partnership with Young People in Recovery, one of the addiction field’s prominent patient advocacy groups, which “will provide expertise on how young individuals seek and access treatment through online resources,” according to an AAC press release.

Meanwhile, the lawsuits against AAC filed by the families of Arbuckle and Johnson slowly move forward; the Johnson case is slated for trial in the spring of 2020. An earnings report filed last week spelled out the ramifications of so-called “patient safety incidents”: “From time to time, we are subject to claims alleging that we did not properly treat or care for a client [or] that we failed to follow internal or external procedures that resulted in death or harm to a client.” Such incidents could lead to government investigations or lawsuits, it acknowledges, and “could diminish public perception of the quality of our services, which in turn could lead to a loss of client placements and referrals, resulting in a material adverse effect on our business.”

While AAC’s future is unclear, what is certain is that the rehab boom is far from over. Ventrell, the rehab trade group director, said he regularly gets phone calls from private equity fund managers who want to invest in rehab companies. He never knows quite how to respond: He appreciates their willingness to invest in addiction treatment but he worries about the focus on profit. “All of a sudden, big business is coming in,” he said. While some might argue that investment will help companies provide more efficient, higher-quality service, he continued, “I haven’t seen that to be true. Quite the contrary.”

Tami Mark, who researches behavioral health financing at think tank RTI International, takes the long view. She started studying the addiction industry back in the ’80s, in the midst of the cocaine epidemic. “At that time, a lot of money flowed into the industry,” she said. “There was concern, similar to now, about some bad actors, and some questions about whether some treatments [were] really effective.” Next, insurance companies backed out of covering treatment, private equity lost interest, and money flowed out. Treatment rates went down. “And we went along our way until we had the opioid epidemic,” she said.

Treatment rates have improved dramatically, but standards of care and reporting haven’t changed a whole lot from a few decades ago. As Mark put it, “Unless we have some kind of systematic change where we have transparency and quality reporting [like] every other health care industry at this point, we’re going to see these occasional cycles and scandals.”