Dano Wall's Harriet Tubman stampDano Wall

Since 1980, the US government has circulated more than 64 billion pocket-size portraits of a slaveowner, ethnic cleanser, and “Indian killer”. And that’s only a fraction of all the $20 bills printed since President Andrew Jackson’s portrait was first put on them in 1929. The Obama administration attempted to rectify this with a plan to swap out Jackson with abolitionist, Union spy, and Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman. Last week, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said his department wouldn’t get around to putting those redesigned $20s into circulation until 2028. (Coincidentally, President Donald Trump has spoken out about taking Jackson off the bill and has made no secret of his admiration for him.)

The administration’s decision to postpone the $20 makeover has inspired some Americans to make their own Tubmans. An artist named Dano Wall has been making stamps of Tubman’s face that can be used to blot out Jackson’s on the $20. (After Mnuchin’s announcement, the stamp sold out on Etsy, though you can also make your own.) Wall told the Washington Post that he’d like to get thousands of stamps out there: “If there are 5,000 people consistently stamping currency, we could get a significant percent of circulating $20 bills [with the Tubman] stamp, at which point it would be impossible to ignore.”

Now that’s more like it #tubmanstamp #harriettubman #tubmantwenty https://t.co/SxxVeQWrWz pic.twitter.com/4nvfE5P5Jw

— tubmanstamp (@tubmanstamp) April 18, 2019

Despite the improbability of achieving widespread visibility, the idea of turning greenbacks into vehicles for political messages isn’t new. (It’s illegal to deface US currency, but it seems that no one’s ever been prosecuted for stamping bills.)

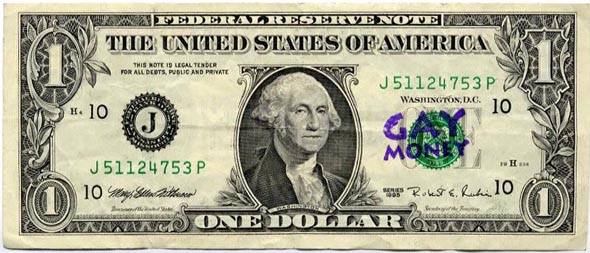

In 1976, a numismatician collected a $2 bill stamped “These Are Farm Dollars.” One dollar bills featuring George Washington with a superimposed speech bubble saying “I Grew Hemp” have been around since the ’90s. In 1993, bills stamped “Gay Money” popped up; “Lesbian Money” and “Bisexual Money” were also spotted. After September 11, an artist named David Greg Harth stamped dollar bills “I Am Not Terrorized” and “I Am Not Afraid”; he claims that 1 million were distributed over three years. Stamped messages collected in the 2000s include: “Jews for Clinton,” “Impeach Bush,” and “Stop Starbucks!”

More recent sightings include bills stamped by Obama conspiracy theorists (“Where’s the Birth Certificate?”) and gun owners. The site occupygeorge.com offers templates for printing infographics about income inequality onto bills. “Currency interventions” by artist Joseph DeLappe print rising sea levels and drones on banknotes. You can buy a “Donald Trump Lives Here” stamp meant to be applied to the image of the White House on the back of the $20 bill. (There’s also a “Hillary Clinton Does Not Live Here” version.)

Most bill-stamping is unorganized and untraceable. That’s part of its appeal, writes Stephen Gencarella Olbrys, an associate professor of communications at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in a paper on “currency chains”:

The number of active participants in currency chains cannot be known with certainty. One bill may speak for thousands. Rubber-stamped “Farm Dollars,” “Gay Money,” “Logger’s Money,” “Atheist Money,” or “GUN OWNER$” money, for example, make ambiguous the size of a presumed minority and suggest a legion deserving notice.

Or, as one DIY stamper tweets, “stamping dollar bills is fun and gets the message out.”

Stamping dollar bills is fun and gets the message out. It's easy – just go to your local stationary/printer or staples & costs about $30 or $40/stamp & reinkable & lasts a long time/be creative. Always keep $20 to $40 in stamped money in your purse/wallet, just spend normally! pic.twitter.com/rALNwPxGMi

— Paul Lozowsky (@PaulLozowsky) December 22, 2018

Occasionally, there are more organized efforts to repurpose cash as political messages, like Ben & Jerry’s cofounder Ben Cohen’s Stamp Stampede, which says it’s enlisted 100,000 Americans to imprint dollar bills with messages promoting voting rights and money in politics (“Not to be Used to Bribe Politicians”).

Yet even a dedicated stamping campaign has to do a lot of work to get noticed. (Stamp Stampede optimistically assumes that every bill is seen by 875 people, and notes that $20 bills circulate more slowly than other denominations.) Let’s say that the Tubman stamp ends up on 1 in 100 bills, making it, as Wall hopes, “impossible to ignore.” That would require 5,000 dedicated stampers to each update $376,000 worth of bills—or one percent of the 9.4 billion Jacksons currently in circulation. Given that the average American carries about $60 in cash, they’d better get stamping.