Michael Ainsworth/AP

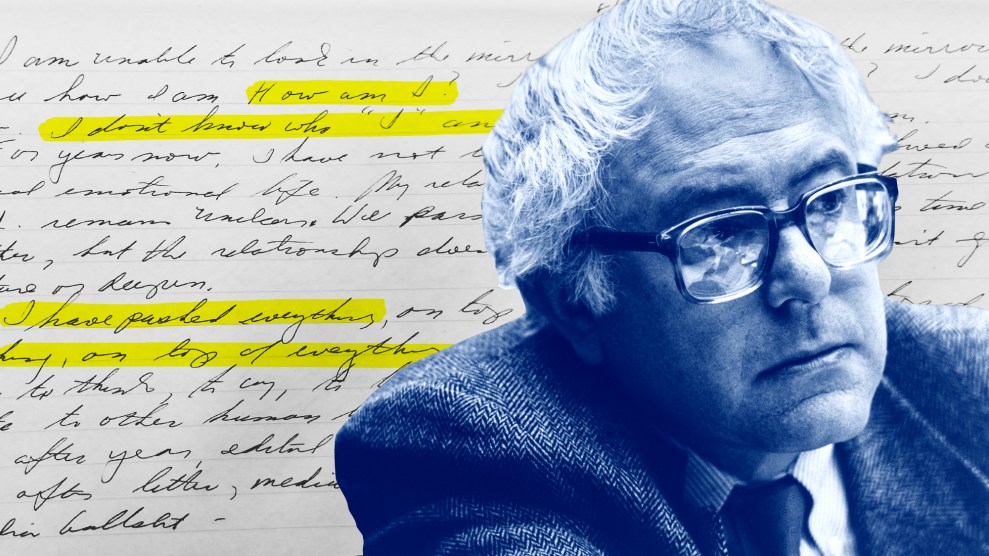

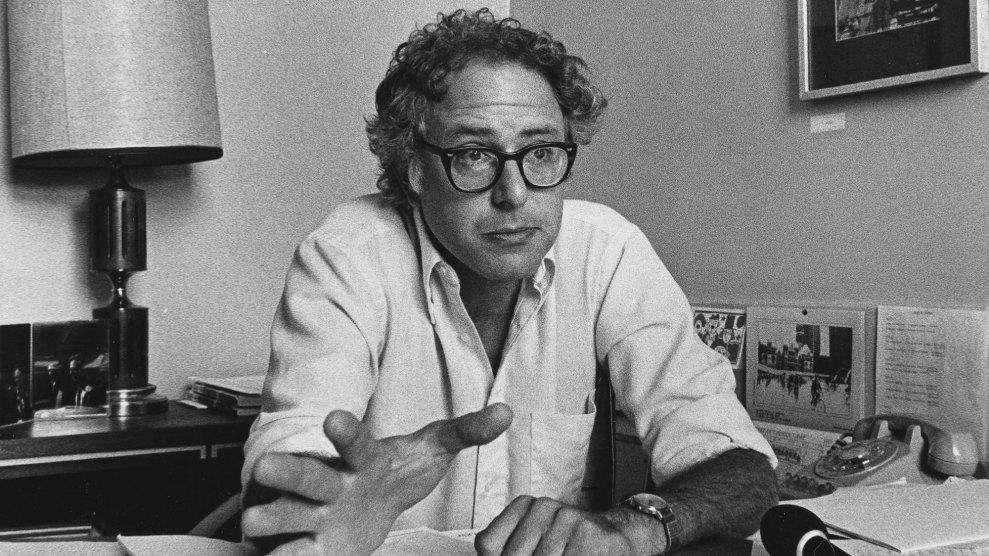

In the spring of 1988, in the middle of a bruising campaign for Congress and one day after tying the knot at a park on Lake Champlain, Bernie Sanders and his wife, Jane, boarded a flight with a small group of Vermonters for a 10-day trip to the Soviet Union. Sanders, who was then mayor of Burlington, later described the tour as “a very strange honeymoon” in his 1997 memoir, Outsider in the House. But it was more than that—it was also a very strange business trip.

The 12-person delegation, which included representatives from the city government, the Chamber of Commerce, and other civic institutions, hoped to break down “international barriers of hatred and mistrust,” Sanders explained in a letter to the editor of the Rutland Daily Herald prior to the departure. Specifically, he aimed to formalize a sister-city relationship with Yaroslavl, a city of about half a million people 160 miles north of Moscow—the latest addition to an ambitious foreign-policy portfolio that had already taken the mayor to Managua, Nicaragua, a few years earlier.

Sanders’ Soviet adventure, the subject of recent front-page stories in the Washington Post and New York Times, remains an object of fascination more than 30 years later. A Republican National Committee email about the trip depicted Sanders’ head surrounded by sickles and hammers. The conservative columnist George Will has called the trip—which coincided with President Ronald Reagan’s own visit to Moscow—a symbol of the senator’s “moral obtuseness.” Invoking the Yaroslavl trip in February, Donald Trump Jr. tweeted sarcastically: “He literally wants the US to become the USSR. But Trump is the Russian agent.” It’s become a gateway joke for Red-baiting.

The actual record of what happened on the trip is limited. Sanders’ entourage included no local journalists, and for more than a week, Burlington residents were mostly in the dark about what their mayor was up to on the other side of the world.

One member of the delegation was documenting the trip: Burlington’s city clerk, Michelle Weiss. Assisted by her companions, Weiss shot hours of footage of the expedition. But for years her tapes, whose existence was first reported by Politico, have collected dust at the Burlington offices of the CCTV Center for Media & Democracy. Though they are listed in the station’s online archive, CCTV executive director Lauren-Glenn Davitian told me in an email that it had no plans to make them available for purchase or distribution—with the exception of a couple minutes of boozy footage that were inadvertently included in a 2015 compilation video—because the videos had never aired. It was in a sort of archival purgatory. But, she added, if I wanted, I could drop by the station and watch the tapes myself. So, one morning in late April, I did.

It is June 9, 1988, the penultimate day of the trip, and Jane Sanders and her husband are riding in a horse-drawn carriage on a small farm outside Yaroslavl. The carriage driver is wearing a puffy red shirt and a black vest, like something out of a Bruegel painting.

“That was wonderful—very nice people,” Jane says as she disembarks. Bernie cracks an inaudible joke—something about gymnastics. A few minutes later, they are on a bus outside a war memorial. Their Soviet guide grabs a microphone and says, “Let us exchange. We shall enrich one another.”

That’s how the footage begins, and for the most part, that’s how the next four hours unfold: long periods of inactivity, occasional moments of cross-cultural enlightenment, maddening inattention to sound quality. A recent Politico story described Sanders’ Burlington TV show, Bernie Speaks to the Community—which ran about the same time—as “a gift to his 2020 rivals,” offering hours of footage of Sanders discussing international relations, drug policy, and the media. Well, anyone looking for a smoking gun with the Soviet Union footage will come away disappointed—the big secret of Bernie’s secret Soviet tapes is that they’re boring.

Sanders arrived in Moscow at a pivotal time. The Soviet Union in 1988 was a city in the throes of economic and political upheaval. Mikhail Gorbachev, who had been general secretary of the ruling Communist Party for three years, had embarked on a slate of political and economic reforms—glasnost and perestroika—and struck up a rapport with his American counterpart, Ronald Reagan. Upon arriving, the Vermonters do what most tourists might have done in the Soviet capital in 1988—they contrast the old with the new. They marvel at the glittering subway, with its chandeliers and stained glass. They walk around Red Square and debate whether to wait in line to see Lenin’s Tomb. They admire the trickle of Western culture that has begun to seep through the Iron Curtain—a record store, a pizza joint, a guy in a Ben & Jerry’s T-shirt. “We know our way around the city,” Bernie kids, as they stand at a crowded intersection. “Been giving directions to everybody.”

Zipping around town on a bus, they pass the Bolshoi Theatre and, a few blocks later, the imposing, neo-Baroque KGB headquarters on Lubyanka Square. “Be well behaved,” their guide says. “Go to Siberia from here!”

After three days of sightseeing, the group heads to Leningrad (as St. Petersburg was still known), where they’re serenaded by a taxi driver and visit an apartment building to see how Soviet citizens live. As they look around and chat with their hosts, Bernie wants to say something through an interpreter. “It is important to try to translate this,” he says. “In America, today, in general, the housing is better than in the Soviet Union.”

Throughout the hours of footage, the video never lingers for too long, no matter how significant the moment. Now they’re dipping their fingers in the Baltic; now they’re at a war memorial in Leningrad; now they’re on a boat heading up the Volga.

A boat speeds past and Sanders jokes to the man holding the camera, an alderman named Terry Bouricius, that they have just uncovered proprietary technology and the Department of Defense will want to talk to them. “Don’t panic, Terry!” he says. “The first Western movie picture of a hydrofoil.”

June 5, 1988: They’re at a social club in Leningrad. Sanders, in a fresh twist, is wearing a blazer. He looks at the camera and grins. “I brought my special dancing shoes,” he says. Music is playing and he dances with Jane, bopping his head to the music, dipping Jane backward and pulling her up.

Watching from a safe distance, one of the Vermonters jokes, “The title of this film: Bernardo: An American Embarrassment.” A few minutes later, Sanders sits down at a table. The top button of his shirt is undone. “So tell us, Bernardo,” one of the men says.

“What?” Sanders replies.

“How does it feel to be dancing to Doctor Zhivago in Leningrad?”

“Well, I never thought that I would do that. And you can quote me on that,” Sanders says.

“I did,” the man says.

Sanders freezes for a second. “Nice.”

“You look quite nice though. Nice shoes,” the man says.

“Did you get my dancing shoes?”

“I did.” (He didn’t.)

Later that night, it’s Sanders’ turn to be videographer. “Low light—what does that mean?” he asks, holding up the camera.

“What?” Weiss says.

“Low light,” Sanders says.

“That means it’s dark in here.”

“It only works when I have my finger on the button. Is that correct?” he asks.

“No.”

“Oh,” Sanders says. “It’s recording right now? How do you stop it?”

“Hit the red button,” Weiss says.

“Oh, I see.”

After three days in Yaroslavl—mosquitoes, more apartment buildings, people in sequins dancing to “We Are the World”—their Soviet translator, whom we know only as Ludmila, brings the formal proceedings to an end with an invitation: “So if you wish to, you can go to the sauna. There is sauna for men and woman.”

What follows is the only part of the trip you can see for yourself—a two-minute clip that was included in the station’s hour-long 2015 DVD special, Positively Bernie, and publicized in late 2018 by a member of a group supporting Beto O’Rourke’s presidential campaign.

If you’ve watched, you know that they go to the sauna, they wrap themselves in towels, and they drink a lot of vodka. (Though perhaps not Sanders.) The Russians sing, and then Ludmila says that by tradition the visitors must reciprocate. “Oh no,” one of the Vermonters says.

“Today, the distinctive feature of our economy is competition,” Ludmila says. Another Soviet, pouring Stoli into his glass, adds, “It is very important.”

“What are we gonna sing?” one of the Vermonters asks. Someone suggests “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

“No, we have to do something appropriate,” another one says.

So they sing “This Land Is Your Land,” and then it’s time to exchange presents.

“We have small gifts for you from a place that knows Moscow girls really knock us out,” one of the Vermont men says to Ludmila, riffing on some Beatles lyrics. Jane gives someone named Sasha a button from Sanders’ congressional campaign and a shirt that says “Burlington–Yaroslavl: Cities of Friendship.”

“Thank you. I shall wear it,” Sasha says, drawing laughs, as he puts the pin on. “I will be a supporter!”

“Bernie Sanders wins by one vote—this guy Sasha from Yaroslavl,” someone says.

Finally, it’s Bernie’s turn. Still wearing a towel, he starts pulling objects out of a rumpled brown paper bag: “And Mayor Riabkov, we give him some delicious Vermont candy, maple syrup candy. This is very sweet.” Sanders reaches into the bag and pulls out a cassette. “And for your lovely daughter, the Beatles.” He pulls out another. “The Throbulators!” He pulls out another. “Oh and—” The Burlingtonians let out a yelp. “And this is a tape that I recorded with many Vermont singers!” Sanders says.

“You were singing?” Ludmila asks, a little incredulous.

“They were singing, I was talking,” he says, continuing to pull gifts out of the bag. “And uh, this is a ‘Bernie for Burlington’ pin.”

It is hard to draw sweeping conclusions from four hours of b-roll. But this is not the smoking-gun footage of a man of who, in the words of Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), “went to the Soviet Union on his honeymoon and I don’t think he ever came back.” At one point in the video, Sanders does a double-take when their guide talks about the cost of housing in Moscow. (“Terry, what’d she say? She said rents haven’t been raised since 1920?”) He is struck by the way the state subsidizes the arts and how well the subway works. But Sanders is also aware that the Soviet system is falling apart.

“I went there expecting them to say, ‘Well, everything is great, there’s no problem,’ but that certainly wasn’t the case,” he told reporters when he arrived back in Burlington. “They were proud of the fact, for example, that their health care system is free, but they would be open to acknowledge that it’s probably 10 years behind the United States in terms of medical technology.”

If there is a through line, it’s Sanders’ basic curiosity about the Soviet people and how they live. In an interview with Mother Jones, Sanders recalled walking into Riabkov’s Yaroslavl apartment and finding his young daughters listening to the Beatles. “I met a lot of really nice people who wanted a closer relationship with the United States,” he said.

In his second run for president, the 77-year-old Sanders has responded aggressively to those who cast his Burlington diplomacy in an unflattering light. After the New York Times published a deep dive into his mayoral foreign policy—including the sister-city friendship with Yaroslavl—he called up the reporter to defend his record. When we spoke a few days later, Sanders confronted the critics of his Cold War politics.

“I know that my political opponents think that because I went to the Soviet Union that I supported authoritarian communism,” Sanders said. “That is an absolute lie. If you check out my record, from day one, I have been critical of the Soviet Union—and unlike Donald Trump, critical of Saudi Arabia, critical of countries around the world that do not respect human rights and democracy.”

The visit, as he explained it, was about peace.

“Our efforts there was to try to prevent war [and] try to bring people together, and that is what I believe is the right thing that we should do,” he said. “My Republican colleagues may not like the fact that I, as a young man, opposed the war in Vietnam, as a congressman led the effort against the disastrous war in Iraq, helped pass a resolution under the War Powers Act for the first time in 45 years to get the US out of a Saudi-led intervention in Yemen, and I will do everything I can to help prevent a war with Iran. Maybe my Republican colleagues don’t like that. But I make no apologies for trying to use every avenue available to bring people together and prevent war.”

The bonds forged on Sanders’ trip to the USSR still hold. The visit was the beginning of a long relationship between residents of both cities. Over the years, there have been school exchange programs, visits by official delegations, and an exhibition hockey game between teams from the Russian city and the University of Vermont. When a Wall Street Journal reporter visited Burlington-on-the-Volga in 2016, residents recalled the American delegation fondly. As one man, a doctor, put it, “We remember him, we respect him, we appreciate him, and we’ll be rooting for him.”

The footage ends where it began. It’s June 9, 1988, and Bernie, Jane, and the rest are back at the farm, somewhere outside Yaroslavl. The segment is short and choppy, the audio garbled, the videographer unusually fascinated by horses. Finally, they’re all standing beside the buggy and the newlyweds hop in.

The horses begin to pull them out of the picture, but before they do, Sanders waves and gestures to the road ahead, and this time we hear his joke.

“A long way to Congress,” he says.