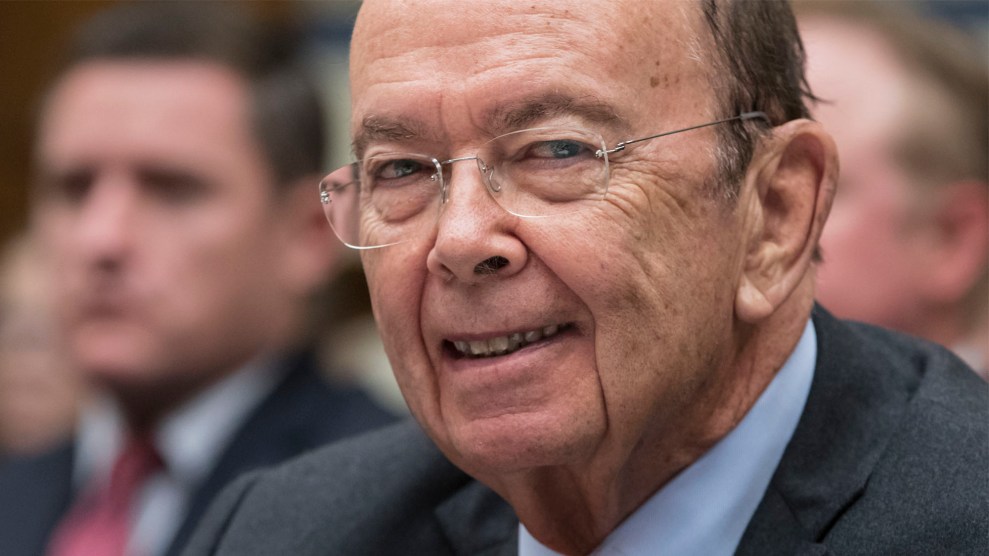

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross appears before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform to discuss preparing for the 2020 Census, Oct. 12, 2017. J. Scott Applewhite/AP

The Supreme Court ruled on Thursday that the Trump administration failed to provide an adequate justification for adding a controversial question about US citizenship to the 2020 census. The ruling sends the case back to the administration to come up with a better reason for adding the question, leaving the fate of the question up in the air. For now, it’s off the 2020 census form.

The census is constitutionally mandated to count every person in America, but civil rights groups say the citizenship question will deter immigrants from responding out of fear that the administration will use their citizenship information to initiate deportation proceedings against them. A large undercount of immigrant communities will shift economic and political power to areas that are whiter and more conservative. The stakes are huge: The census determines how $880 billion in federal funding is allocated, how much representation states receive, and how political districts are drawn.

Three lower-court decisions struck down the question and were followed by late-breaking bombshell evidence showing that the GOP’s longtime redistricting mastermind had initiated the push for the question because he believed it would be “advantageous to Republicans and Non-Hispanic Whites.”

The Trump administration said the question was needed to better enforce the Voting Rights Act, but nearly every piece of evidence in the case undercut those claims. The administration hasn’t filed a single lawsuit to enforce the VRA, and the court’s conservative majority gutted that very law in 2013. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who oversees the Census Bureau, said the Justice Department requested the question, but in fact it was Ross who first lobbied for it, after consulting with anti-immigrant hard-liners inside and outside the administration, including Steve Bannon and Kris Kobach (although Ross initially denied having discussed it with them).

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote on Thursday that Ross had the authority to add a citizenship question to the census but agreed with the district court in New York that his invocation of the VRA was dubious. “The record shows that the Secretary began taking steps to reinstate a citizenship question about a week into his tenure, but it contains no hint that he was considering VRA enforcement in connection with that project,” Roberts wrote. “Altogether, the evidence tells a story that does not match the explanation the Secretary gave for his decision.” He continued, “We are presented, in other words, with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decisionmaking process.”

Roberts concluded that the administration’s argument that it needed the question to better enforce the VRA “seems to have been contrived.”

The Census Bureau opposed the addition of the citizenship question, which its top scientist warned in a January memo was “very costly, harms the quality of the census count, and would use substantially less accurate citizenship status data than are available from administrative sources.” When the bureau asked to meet with the Justice Department to voice its concerns, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions blocked lawyers in the department’s Civil Rights Division from doing so. John Gore, the former assistant attorney general for civil rights who drafted the letter formally requesting the citizenship question, agreed with an ACLU lawyer during a federal trial in New York that it was “not necessary” to enforce the VRA.

There is ample evidence, however, that the question would deter immigrants from filling out a census form. The Census Bureau estimated that it could cause as many as9 million people not to respond to the census and increase the cost of conducting it by millions of dollars. (People could fill out the census form but skip the citizenship question, although they could be fined for doing so.)

A recent study of Latino immigrants in California’s San Joaquin Valley, which is 50 percent Hispanic, found that fewer than half of respondents would respond to the census if it included a citizenship question. I found the same fear about a citizenship question when I spent time with Latino immigrants in California’s Central Valley last year for a feature on the census:

“I wouldn’t answer the form if that question is on,” said Ana, a farmworker and mother of three from Parlier, California, which is home to many migrant farmworkers. “The word ‘citizen’ scares us. There’s a lot of tension in the country right now.” At a community meeting in nearby Huron, California, another Latino immigrant named Erica told me, “Once they see that question, forget it. People will throw the form away.”

A large undercount of Latinos could cost states like California congressional seats and billions of dollars in federal funding. But that’s not the only way the citizenship question could shift power to Republican areas.

Republicans could use the citizenship data to draw state legislative districts based on citizenship rather than total population, a move that would benefit GOP areas with fewer immigrants. In a 2015 study, Tom Hofeller—the GOP redistricting expert behind the citizenship question—wrote approvingly that this would be a “radical departure from the federal ‘one person, one vote’ rule presently used in the United States” that would hurt Latino representation but increase the number of seats held by white Republicans.

The Trump administration must now come up with a better rationale for adding the question. That reasoning would then be reviewed by a federal district court in New York—the same court that struck down the question in the first place. Meanwhile, a federal judge in Maryland, who struck down the question in April, is planning to reopen his case to examine whether the administration added the question to discriminate against Hispanics. That gives multiple avenues to block the question going forward.