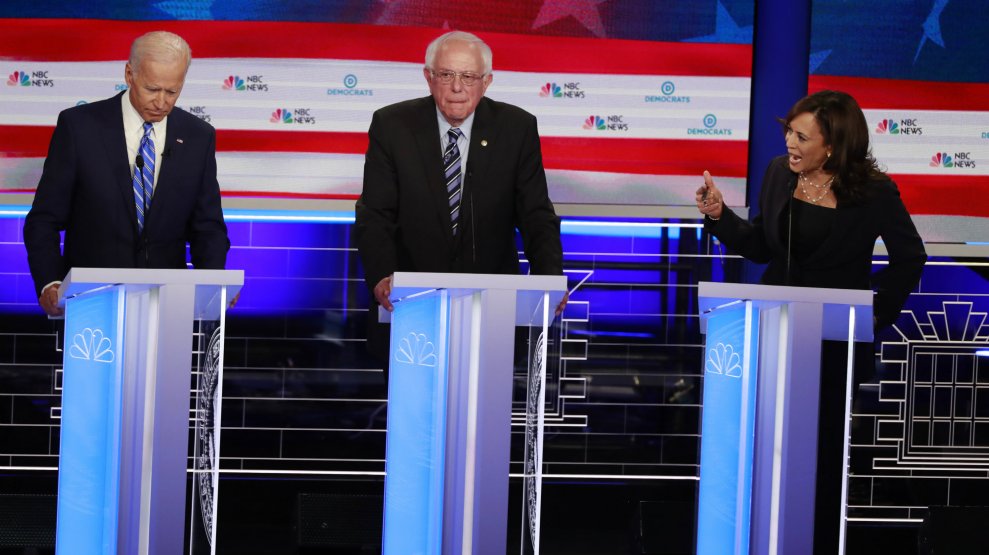

Wilfredo Lee/AP

During the first Democratic debate of the 2020 presidential primaries, Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Calif.), who is 38 years old, turned to 76-year-old former Vice President Joe Biden and said, “If we’re going to solve the issues of climate chaos, pass the torch. If we’re going to solve the issue of student loan debt, pass the torch. If we’re going to end the gun violence for families who are fearful of sending their kids to school, pass the torch.”

Swalwell has since dropped out of the race, but his exchange with Biden embodies one of the important conversations taking place within the Democratic Party: How much should the age of the candidate matter when considering fitness for office and vision for the future? The conversation underscores the chasms among baby boomer candidates like Biden, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Jay Inslee, and Gen Xers like Cory Booker and Kamala Harris, and millennial Pete Buttigieg. It is evident in the rifts between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the “squad” of first-year lawmakers. And much of the urgency of the Sunrise Movement comes from the fact that these young people will grow older as the full force of climate change will bear down.

From conflicts among individual politicians to their approaches to the issues, tensions between generations are playing a significant role in debates about the future of the Democratic Party. But is age really as defining a factor in policy and governing as it may appear?

“We don’t care who is proposing what policy as long as that policy benefits young people,” said Ben Brown, founder of the Association of Young Americans (AYA), a nonpartisan membership organization for people between 18 and 35 that lobbies lawmakers on their behalf. As important as it may be for younger voters to have representatives who share their socioeconomic backgrounds, he said, “We will work with anyone if they are working to better the lives of young people.”

Before the 2018 midterms, several organizations conducted research on the generational divide. The AYA teamed up with the AARP, the largest interest group for Americans ages 50 and older, on what they called the Three Generations Survey. The survey evaluated key concerns, similarities, and differences among millennials, Generation Xers, and baby boomers around finances, voting, and political concerns. Some of the questions were whether student loan debts prevented or delayed actions like saving for retirement or buying a home.

Pew Research Center conducted another study of adults across generations with questions about attitudes toward climate change and energy. It found that despite a common perception that older people care less about climate change, that’s largely a product of political affiliation rather than trends across generations. As Pew highlighted in 2018, “Among Democrats, there are no more than modest differences by generation on beliefs about the climate and energy issues.”

In the 2018 midterm elections, the younger generations, those ages 18 to 53, cast more votes than baby boomers and older generations did. Still, the looming 2020 election has voters thinking about the power of older generations. Atlantic writer Andrew Ferguson argued that the “Democratic Party’s gerontocracy is holding back the political causes it claims to want to advance,” in an article headlined “Tyranny of the 70-Somethings.” “There is a huge gap between where the energy and creativity of the party lie, with a group of dynamic activists and House members in their 30s and even their 20s (thank you, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez),” he wrote, “and the ruling class of 70-somethings layered far above like a crumbling porte cochere.”

But does the “energy and creativity” of the Democratic Party reside only with young people and not at all with the older generation? The stereotypes about older adults that persist in politics are not unlike that of other workplaces. In 2018, I interviewed Brian Heller, a partner in the New York employment law firm Schwartz Perry & Heller about age discrimination in New York City. “There’s a general perception even in New York City that it makes sense for companies to want to get someone younger, that there’s a benefit to youth that can’t be expressed,” he said. “And, that’s a flat-out discriminatory deal. That’s not grounded in anything other than a stereotype.”

Take the question of student debt relief, a problem often considered to be restricted to younger people. The AARP and AYA survey found that 41 percent of millennials, 38 percent of Gen Xers, and 31 percent of baby boomers said student loan debts stopped them from saving for retirement. Last week, 70-year-old Sen. Warren (D-Mass.) and 79-year old James Clyburn (D-S.C.) introduced the Student Loan Debt Relief Act. AYA hired a lobbyist to press lawmakers to act on college affordability and student debt and endorsed the measure.

Michael North, assistant professor of management and organizations at New York University, has researched intergenerational tensions for more than a decade. North’s research shows that older people often face pressure to adhere to the idea of succession, which “prescribes for older generations that they have had their turn at prime influence or prime power and it is for the older generation to step aside and make way for younger generations.” When I interviewed him previously about intergenerational tensions in the workplace, North asked, “Who’s to be the judge, basically, of when it’s time for an older worker to step aside or not?”