Puerto Rico Gov. Ricardo RossellóCarlos Giusti/AP

Outgoing Puerto Rico Gov. Ricardo Rosselló was reportedly involved in a secret group chat that managed a Twitter bot network in order to direct attacks at his political opponents. On Monday, the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab published an investigation dissecting a dozen cases where messages and issues discussed in the governor’s private messaging group made their way to Twitter via accounts that had no obvious connections to the governor.

The investigation examined messages included in an 889-page transcript of a private Telegram chat group—a messaging platform akin to WhatsApp—that included Rosselló and some of his aides and close friends. The transcript, published July 13 by Puerto Rico’s Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (Center for Investigative Journalism), sparked massive protests on the island, and caused a flurry of resignations from the governor’s cabinet and staff, and, most recently, an announcement from the governor himself that he would resign on August 2nd. Much of the attention around the chats has focused on the governor and his friends’ crude and offensive messages that insulted and mocked the LGBTQ community, political opponents, women’s rights advocates, and even victims of Hurricane María. Authorities on the island are also reviewing the messages for evidence of possible corruption, and have opened an investigation.

Luis J. Valentín Ortiz, one of the reporters who published the transcript, told Mother Jones Monday that people on the island had suspected some sort of orchestrated Twitter network was supporting the governor and his pro-statehood party, but they’d never been able to prove it. “Despite a lot of people [knowing] to some degree that some of these accounts were trolls and most likely controlled by people related to the governor’s party, seeing direct evidence in the chat that various top officials controlled them is another thing,” Valentín says.

It’s unclear how involved or aware Rosselló himself was about the operation, but the governor was one of the administrators of the chat group and a frequent participant generally. A spokeswoman for the governor did not respond to a request for comment on the DFRLab investigation.

Luiza Bandeira, Esteban Ponce de León, and Sophie Clark, the authors of the Lab’s report, note that they “cannot say with certainty that the chat participants directed the troll accounts,” but add that the “timing and specificity with which the officials discussed the accounts’ actions within the chat suggest a degree of complicity.” Their investigation found 12 cases where members of the chat group discussed either amplifying a government message or attacking political opponents. In six of those cases, the same 51 Twitter accounts were used to push a message.

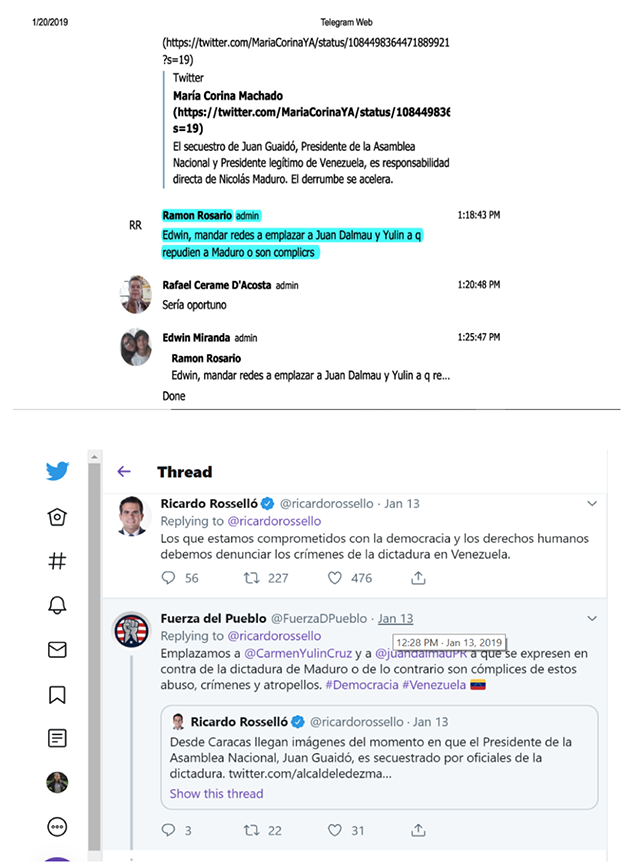

The most blatant case the authors found was on January 13, 2019, after news broke that Juan Guaidó, the president of the National Assembly and opposition leader against Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela, had been detained. Ramon Rosario, Rosselló’s former secretary of Public Affairs and Public Policy, told another member of the group chat to “tell social networks” to challenge two Puerto Rican politicians to repudiate Maduro “or they are accomplices.” Seven minutes later, Edwin Miranda, a friend of the governor and the head of a marketing agency, responded “Done.” Three minutes after that, a Twitter account with the handle “@FuerzaDPueblo” tweeted a message that did almost exactly as Rosario asked.

In another case the governor’s allies trained the network on Colecta Feminista, a local group that has been pushing Puerto Rican leaders—and Rosselló specifically—on justice issues for years. On December 17, 2018 the group posted a tweet calling for protests at the headquarters of the Puerto Rico police. The next day, Rosario posted the tweet in the group chat and told Miranda to “tell [them] to ask when they will protest Marazzi,” a reference to Mario Marazzi, the former head of the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics who had clashed with the Rosselló administration on the Hurricane María death toll, but who had also been accused of domestic violence in October of 2018 and was forced out of his job as a result. An hour later Miranda responded with a tweet from a now-defunct account with the handle “@HablaGuillo,” which called the feminist group “hypocrites.”

Nearly a week later Rosselló mentioned the feminist group and the lack of protests of Marazzi, and Miranda told him “we jumped on them,” and included another tweet attacking the group from the handle “@luisanthony40,” another account DFRLab identified as being part of the network. The investigation also noted that Miranda had once said in the chat he was going to “move” a hashtag that promoted support for police, “#NuestrosHéroes” (OurHeroes). Less than 15 minutes later, @luisanthony40 posted the same hashtag and news article.

Miranda said the report was “false” in a late Monday message, but wouldn’t elaborate.

The DFRLab report includes analysis of the Twitter accounts identified as likely being part of the group, and evidence that they were likely acting as a network, including accounts tweeting the same content nearly 200 times in one case, and dozens of times in other cases. The report notes that the activity cannot be attributed to the governor’s circle “with certainty,” but noted that the group “explicitly celebrated specific posts” and “were, at the very least, aware of the existence” of the Twitter accounts. But, the authors conclude, “the uncanny degree of specificity with which, and unusually close timeframe within which, the accounts carried out some of the initiatives discussed in the chat suggested that the account operators were privy to some of the details of the officials’ conversation.”

This story has been updated.