It was like the first day of camp, but with blazers and better snacks. Three dozen of the most liberal lawmakers in the House of Representatives were gathered on the fifth floor of a House office building on the afternoon of January 10. New members, sworn into office just one week earlier as part of a historic majority-making midterm wave, exchanged pleasantries with returning incumbents as they helped themselves to falafel, brie, and fruit salad from a makeshift buffet along the room’s back wall. There were reunions and introductions; there was the promise of new beginnings. All that was missing was a campfire and friendship bracelets.

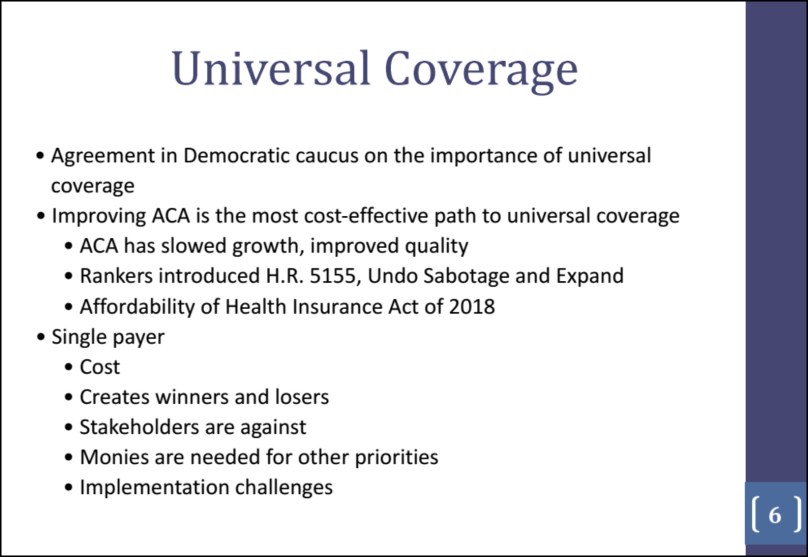

This was a gathering of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, a group of lawmakers whose advocacy of bold economic and social justice reforms over the last 28 years has often defined Congress’ leftmost flank. The CPC, as it’s known on the Hill, hasn’t achieved household-name status, but its founder, Bernie Sanders, and most famous new member, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), have. The group has been the point of origin for proposals that have lately moved from the fringe’s wish list to the Democratic mainstream. Single-payer health care, debt-free college, and universal child care trace their modern legislative origins to the CPC.

The group had good reason to be excited that day. As Democrats wrested more than 40 seats from GOP control, the CPC’s footprint grew, too. Nearly 20 House freshmen who put liberal tenets at the heart of their campaigns joined the caucus after the November midterms, as did a number of longtime incumbents who formalized their relationship to the group that valued their progressive priorities. Suddenly, the CPC had 95 members, accounting for more than 40 percent of the House Democratic caucus and nearly a quarter of the entire chamber—which, in the words of CPC co-chair Mark Pocan (D-Wis.), gave the caucus a chance to “flex its muscles.”

The flex would begin early, judging from the ambitious to-do list that the caucus’ co-chairs, Pocan and Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), ran through over the next hour at the group’s first meeting of the year. Jayapal told her colleagues she’d soon release her Medicare for All bill, a much-anticipated revision of Sanders’ 2017 legislation and a long-standing House bill that was already generating admiration and disdain on the 2020 campaign trail. The caucus was preparing an amendment strategy for HR 1, the sweeping anti-corruption bill that House Democrats made their top priority in the new session. Jayapal called the bill “a fantastic start” but suggested it ought to be strengthened, especially concerning the disclosure of President Trump’s tax returns. Before they broke, Jayapal reminded the members that the caucus was hosting an off-the-record happy hour with the media that evening. Eighty reporters had RSVPed—a quantity that raised eyebrows from a roomful of lawmakers unaccustomed to the spotlight.

With a newfound Democratic majority, Jayapal and Pocan see their moment in the 116th Congress. Here is where Democrats can at least settle debates about what the party stands for, with a push from liberal lawmakers who speak for the Democratic base and bold reforms they believe drew voters to the polls in 2018. But the CPC’s efforts to call attention to a progressive legislative agenda—especially through the megaphones of its energized, outspoken new members—has provided fodder for Republicans, who condemn caucus members as out-of-touch socialists, and for moderate Democrats who say it has given Republicans too much ammunition. Not that the caucus is a united body. Some members push for a more aggressive approach in its negotiations with Pelosi and House leadership and are convinced the CPC should operate with sticks, not carrots. Others see benefits in lining up behind leadership while the party debates its best strategy for defeating Trump behind closed doors. The caucus is itself a big tent within the bigger tent of the Democratic Party.

During the first 100 days of the 116th Congress, I embedded myself in the inner workings of the CPC. I wanted to observe how this group of emboldened progressives would approach its new position of power. What I saw was an old story in new form: the party beginning the fitful process of absorbing the ideas and energies of its wing.

Several months after they began, right before the August recess, all the tensions I witnessed during those first 100 days—questions of whether to work with House leadership or rebel against it, whether to demand caucus unanimity or use its size to wield strength—blossomed into public combat between Pelosi; the caucus leaders; four of its most prominent progressive newcomers, who by virtue of a photo they posted on their first trip to Washington as congresswomen-elect had come to be known simply as the squad; and, of course, President Trump.

Some members confess that they worry the visibility of the CPC and its high-profile members could sink the Democrats. Others insist it represents what might be the brightest hope for their party as they take on not just Trump, but the Republican majority in the Senate. From my vantage point, the group is using the churn of the 116th Congress to lay the groundwork for a progressive future—the success of which will be measured not by purity tests or toeing the line, but by building a coalition whose vision for America has steadily found its way to become the centerpiece of a new Democratic majority.

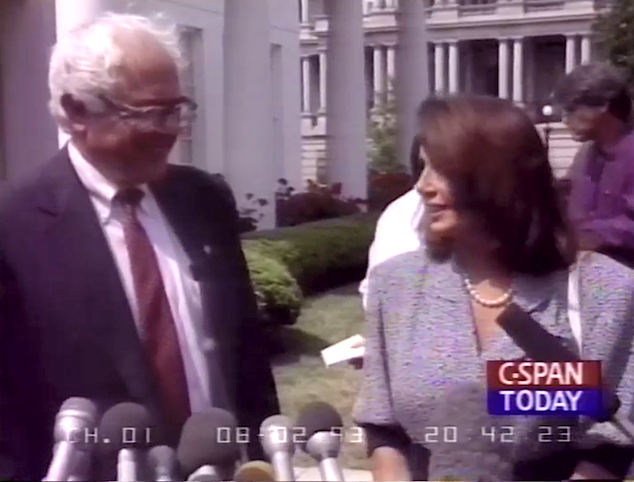

The scene from that January meeting bore little resemblance to the origins of the CPC. Bernie Sanders and a handful of his most liberal House colleagues founded the group in 1991 in an attempt to fill the vacuum of liberal ideas left open during the demoralizing presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush. The caucus had grown to at least a dozen members by the time it made its C-SPAN debut in August 1993, at a press conference that followed a meeting the CPC held with President Clinton to express concerns over a budget bill. “You know, we have the widest gap between the rich and the poor in the industrialized world,” Sanders said, sounding the themes that would echo throughout his two presidential campaigns. Betraying no signs of discomfort under his navy suit in the heat, he added, “I don’t think our job is to worry about the needs of the rich. Somebody’s gotta stand up for working people in this country.”

The network didn’t seem to know what to make of Sanders and his colleagues clustered on the White House lawn that sweltering summer afternoon. It introduced them as “a group calling themselves the Congressional Progressive Caucus” who are looking out for the interests of “quote, working people and the poor.” White House reporters appeared to share in that skepticism, asking Sanders why the coalition was necessary at all.

“We’re not going to tell you that Congress is a particularly progressive institution,” he replied with a chuckle. “But we did think that there were more progressives in Congress than the White House or the American people really knew of, so we reached out and we brought people together to concentrate on a progressive agenda.” Nancy Pelosi, then in her fourth term as a California representative and an early member of the CPC, chimed in to celebrate her colleagues’ success in negotiating an expansion of the earned income tax credit.

Reps. Bernie Sanders and Nancy Pelosi address reporters during a press conference on the White House lawn on August 2, 1993.

C-SPAN

Twenty-six years later, Sanders is running for president again, the CPC has become a force to be reckoned with, and Pelosi is no longer just a member but Speaker of the House, serving as the de-facto leader of the Democrats as the party’s highest-ranking member. The day after the 2018 midterm elections, the ink hadn’t yet dried on the ballots by the time Pelosi asserted her victory narrative: Districts were flipped by moderate Democrats who ran by promising to protect the Affordable Care Act against the multi-pronged assault by Trump and Republicans and to lower the cost of prescription drugs. “Health care was on the ballot,” Pelosi told reporters the day after the election, “and health care won.”

In many respects, she was right. Where Democrats gained House seats, they largely did so with a cast of Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee–backed candidates running on what Pelosi called her party’s “kitchen table issues,” moderates who came to Washington to fix Obamacare, end corruption, and pass an infrastructure plan that would improve roads, bridges, and broadband in their communities. “Most of the freshmen come from swing districts,” Rep. Tom Malinowski (D-N.J.), a member of the business-friendly New Democrat Coalition who defeated five-term incumbent Republican Leonard Lance, told Vox earlier this year. “We come from places where voters want us to focus on getting things done that can actually be achieved.”

Jayapal and Pocan had a different perspective. On the Monday after the election, CPC leaders assembled their newest members-elect for orientation at the AFL-CIO headquarters and ascribed the success to the “very progressive and populist issues” that had found their way into the platforms of all sorts of candidates. “It’s where the feeling of November 6th was,” Pocan told the crowd. Jayapal pointed to raising minimum wage, fighting for universal health care, and protecting collective bargaining rights as values that united the new class.“We call it a new kind of centrism,” she said.

Eight months before the midterms, the CPC’s political arm had commissioned polling in 30 swing districts, and respondents seemed to favor the CPC’s highest priorities. Seventy-two percent of polled voters said they supported “guaranteed affordable health care through an expanded and improved Medicare for All,” the CPC’s marquee issue. More than 40 percent of all House newcomers had backed Medicare for All during their campaigns and nearly half had run on expanding Social Security benefits, according to the Progressive Change Institute, a liberal research firm. Sure, this included newcomers who’d ousted longtime Democratic incumbents from the left, but also some who counted themselves among the House Democrats’ new moderates.

Even more convincing evidence of progressives’ popularity for Jayapal and Pocan was the outsized role that progressive advocacy organizations played during the 2018 midterms. The vast networks of volunteers who signed on with veteran grassroots group MoveOn and powerhouse newcomer Indivisible had managed to get all sorts of Democrats elected, but their ideological loyalties were with the most liberal wing of the House. Indivisible even facilitated the CPC’s new member orientation, coaching groups through an “inside-outside” strategy that would help use their House membership to align with the progressive movement as a whole.

Pelosi may not have shared the CPC co-chairs’ sense of what had transpired, but facing a rebellion from the party’s moderate faction—including more than a dozen district-flipping first-years—she depended on progressives to ensure the Speaker’s gavel would be hers. Jayapal and Pocan seized the opportunity to leverage their newfound size and influence. After the CPC victory lap at AFL-CIO headquarters, the co-chairs met with leaders of prominent progressive groups and asked them to withhold endorsing Pelosi as speaker until their caucus could secure some privileges commensurate with its growth. Polling conducted by Indivisible revealed that their members would prefer a speaker more progressive than Pelosi—though no one challenged her. “Given the options on the table, Pelosi was the most progressive,” Indivisible co-founder Ezra Levin says, calling it an opportunity “to work with the CPC and try to extract some kind of concessions—to say, ‘Yes, we will line up behind Pelosi,’ but they would also like to see something coming out of it.”

When CPC co-chairs received guarantees of proportional representation across key House committees—like Financial Services and Judiciary—on November 15, Jayapal and Pocan released their hostages. Indivisible and MoveOn tweeted their support of Pelosi’s return to the speakership that night, and Jayapal gave Pelosi a full-throated endorsement the next morning. “No one can really doubt Pelosi’s progressive chops,” she told Politico.

But those “progressive chops” had been tested just four hours after Jayapal and Pocan had told reporters about their vision for Congress. Two of the freshly anointed squad members, Reps.-elect Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), rallied with members of the Sunrise Movement, a group of youth activists pushing for strong legislative action to combat climate change. Still wearing the blazers and heels they’d worn to the press conference earlier that day, Ocasio-Cortez and Tlaib stood on top of folding tables in a Washington church basement and declared the Koch brothers “assholes.” The next morning, the two newcomers joined the activists again in protests to demand a committee on climate change on Capitol Hill, finally arriving at Pelosi’s office, where they staged a sit-in.

Ocasio-Cortez had texted Jayapal to let Jayapal know she’d joined the protest. “And I was like, ‘Great,’” Jayapal recalls. “I’m an organizer. I see this energy as being fabulous for the movement.” The Washington representative was no stranger to neophytes making bold moves: She challenged the electoral college vote during her first week, in January 2017. (“It is over,” then–vice president Joe Biden scolded as he gaveled Jayapal down.)

Pelosi welcomed her office visitors with grace, calling off the Capitol police and taking to Twitter to share how she was “deeply inspired by the young activists & advocates leading the way on confronting climate change.” But the soon-to-be House speaker stopped short of supporting the Green New Deal, the overarching vision for federal investment in green infrastructure to transition the United States off fossil fuels.

Jayapal and Pocan relished the energy this new group of lawmakers brought to the caucus, but relishing the energy was not to be confused with being willing to move forward with their demands wholesale. In early December, Jayapal and Pocan sat down with Ocasio-Cortez and the Sunrise Activists to praise their determination while urging them to channel their energies into the procedures and precedents of Congress. The conversations resulted in tweaks to the activists’ initial vision that brought a handful of influential House members on board. “It’s not just people showing up in an office,” Jayapal told me back then. “It’s also all the work that goes on behind the scenes—all the relationships that have to build, and the trust.”

Congressional Progressive Caucus co-chairs Rep. Mark Pocan (D-Wisc.) and Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) update reporters on progressive priorities at the Capitol in Washington, Friday, May 17, 2019.

J. Scott Applewhite / AP

Pelosi may have been gracious during the sit-in, but her contempt for the CPC’s priorities had been palpable since the 116th Congress convened. In January, the newly gaveled House speaker told Rolling Stone, “Medicare for All is not as good a benefit as the Affordable Care Act,” drawing upon her conviction that the proposals for universal health care distracted from her efforts to protect the Affordable Care Act from Republican attempts to dismantle it. She cited the more than $30 trillion price tag that a libertarian policy center had tied to Sanders’ Senate version of the bill and scoffed, “How do you pay for that?” (With the headline “Women Shaping the Future,” that issue of Rolling Stone featured a portrait of Pelosi beaming alongside Ocasio-Cortez, Omar, and new Connecticut Rep. Jahana Hayes on the cover.)

A month later, Pelosi heralded the Green New Deal as the “green dream or whatever they call it—nobody knows what it is, but they’re for it, right?” At the symbolically important 100-days benchmark, Pelosi joined Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes and distanced herself from her progressive colleagues. “That’s, like, five people,” Pelosi told Stahl.

Using Congress to debate big ideas has irked party standard-bearers who worry that voters will measure Democrats in 2020 by their willingness to compromise with Republicans, not each other. This was the message House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) had for the CPC when he visited the caucus on January 15, the week after the group’s inaugural gathering. The Democrats’ second-in-command fielded questions from CPC members about whether House leadership would tackle climate change, student debt, and women’s reproductive rights. In his responses, the 20-term elder statesman placated their concerns by deferring to the structures that had been in place long before he got there and would exist long after he left—in this case, the committee chairs who’d be taking on these issues.

The tone shifted at the conclusion of his visit from friendly engagement to stern admonition: 2018 was the most important election of his lifetime, seconded only by 2020, he told the group. Passing legislation to get things done should be top of mind, something he acknowledged could be a constraint on the caucus. A number of lawmakers met his parting words with tight smiles and slow nods.

(In a statement he sent when I asked about the meeting, Hoyer said House Democrats “are going to continue to work together to advance our shared values and goals, demonstrate our ability to govern, and present an alternative vision for the American people, and I look forward to continuing to working closely with the CPC to do so.”)

With scant support from leadership, Pocan and Jayapal needed to chart their own course to advance their priorities, and they did so by turning the caucus into a direct pipeline for the desires of members’ constituents. “Vulnerable members are going to be risk-resistant,” Pocan says. “But if we can prove to people on any issue that their constituents actually want it—they don’t have to be afraid of their constituents, right?” He relied on the group’s swing district polling, which had convinced Pelosi to take them seriously before the new Congress convened. Pocan pointed to broad support for expanding Social Security “by eliminating the cap for the highest income earners so everyone pays their fair share,” “end tax breaks for corporations who ship jobs overseas, and wealthy individuals who shelter their income abroad,” and “lower prescription drug prices by allowing Medicare to negotiate prices, just like the VA.”

The co-chairs lined up behind House Democrats’ key positions, even as they advanced their own big ideas. When the speaker unveiled her own legislation to shore up the Affordable Care Act in March, the co-chairs were quick to add their names to it. Proving that they backed the speaker’s priority would be critical, a Jayapal staffer said—especially as the co-chairs continued to rely on Pelosi’s good graces to advance their agenda. As they did, Pelosi seemed to momentarily soften on staunch opposition to the CPC’s marquee bill. “Let’s use the word ‘LOVE,’” she told her caucus during a closed-door meeting. “It means, ‘Let Other Versions Exist.’”

Pressuring and appeasing Pelosi yielded some victories. The co-chairs managed to inject their brand of leftist populism into a number of the House’s priorities, including Democrats’ landmark anti-corruption package they began strategizing about on the first day the CPC met. Their efforts to get proportionate representation on key committees had led to viral videos that drew attention to their policy goals, as when Ocasio-Cortez grilled Trump attorney Michael Cohen from her position on the House Oversight Committee. In April, the co-chairs whipped enough votes to quash a bill that would have continued to increase defense funding, when their priorities were greater spending on domestic programs. “House Dems cancel vote on budget plan amid internal revolt,” Politico declared.

Long before there was an AOC or a CPC, there was the Democratic Study Group. Created in 1959—Bernie Sanders was still a teenager—the DSG, like the CPC, grew out of the thwarted hopes of liberal lawmakers. During the 1950s, Democrats held control of the chamber for much of the decade, but bills proposing a national health insurance plan, affordable housing, and civil rights languished as Southern Democrats, often siding with Republicans, stymied reforms that offended the Southern lawmakers’ segregationist sensibilities.

Their early days bear more than a passing resemblance to the CPC’s efforts today. The DSG lobbied House Speaker Sam Rayburn to appoint their members to the most influential committees and rounded up votes to counter Dixiecrats’ attempts to derail their civil rights policies. In its version of the inside-outside strategy, the DSG enlisted labor unions like the AFL-CIO and progressive advocacy groups like Ralph Nader’s new creation, Public Citizen, to wage a grassroots campaign to pressure lawmakers to support its platform. DSG also served as a clearinghouse for research and data to inform a progressive legislative agenda.

Mike Darner, who’s served as the CPC’s executive director and top staffer since 2014, says the CPC embodies many of its predecessor’s characteristics as it pushes leadership not to give in to the party’s conservative faction. “It’s like that on an issue-by-issue basis,” he explains. “Our members don’t agree on everything, but they’re ideologically coherent enough that we can leverage huge numbers of our members.” A sizable bloc, Darner explains, can stop leadership from bringing a bill to the House floor and create a starting point for negotiations and compromise.

But much of the DSG’s influence came from its absolutist approach. An aggressive whipping operation ensured members voted along DSG lines; during election years, members worked to increase the group’s size. Nearly half of all House Democrats were DSG members after the 1964 election, making the group larger than the entire House Republican caucus. The House chugged through Johnson’s Great Society agenda, passing Medicare, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, and environmental protections. Its pinnacle was in the aftermath of Watergate, when 75 “Watergate Babies,” most of them DSG protégés, forced long-serving committee chairs to defend their seats in deposition-style testimony. When the Freedom Caucus conducted its scorched earth campaign to extract concessions from Republican leadership, historians looked to the DSG as the pioneer of its tactics.

Jayapal and Pocan have been emphatic that they will not journey down that path. “The Tea Party was the party of ‘no,’ and we’re the caucus of ‘yes,’” Pocan has repeatedly said when reporters ask why the CPC wouldn’t take cues from the GOP group. But some of the CPC’s progressive allies wish they would. Some of the co-chairs’ recalcitrance stems from an unwillingness to impose ideological purity tests on its members, something Darner says has helped to grow the CPC over time. “If you’re a self-identifying progressive, you can come and learn and be a part of the dialogue about what progressives are doing,” Darner says. “The only alternative is just to tell people they can’t be a part of that, which I don’t think is a good outcome.”

But some of the CPC’s progressive allies wish the caucus would take a tougher stance. At the dawn of the 116th Congress, Indivisible circulated a memo to members-elect on how to create a “Freedom Caucus of the Left,” according to the Washington Post. Since I started reporting this story in January, activists closely aligned with the CPC’s mission have asked me if I thought, based on my observations, that the group might take a harder line. And while CPC colleagues describe Ocasio-Cortez as “very much a team player,” she’s floated the idea of progressives voting as a bloc. That’s how she and her fellow squad members have acted on a number of occasions. Back in February, AOC, Omar, Pressley, and Tlaib tried to derail a bill that would end the government shutdown—by that point, the longest in history—over its funding for ICE detention beds, a nonstarter for the group that believes ICE shouldn’t exist.

In July, simmering tensions within the Democratic Party reached a boil. The CPC co-chairs took a hard line to secure provisions in a House border funding bill that would have created basic protections for children held in government immigrant facilities. The House passed the bill and was expected to negotiate with the Senate to keep those provisions alive for that chamber’s vote. But yielding to pressure from its moderate wing, the House let the Senate dictate the terms, passing a version without those provisions in it. A New York Times headline declared the winners: “For All the Talk of a Tea Party of the Left, Moderates Emerge as a Democratic Power.”

Pelosi relished the opportunity to marginalize four of the most visible liberals in her caucus, who were the only four to vote against the initial House bill for the same reason they skipped the February spending bill. “All these people have their public whatever and their Twitter world,” she told the Times‘ Maureen Dowd. “But they didn’t have any following. They’re four people and that’s how many votes they got.”

The vote for the Senate bill and Pelosi’s comments ignited a fire that waged across the House’s Democratic factions during the first two weeks of July. It ended only when President Trump grabbed the mic and turned the feud into a race-baiting campaign line that delighted his base and endangered the lives of the four congresswomen of color. On July 18, Jayapal and Pocan joined the chairs of the House Democratic Caucus and leaders of the New Democrat Coalition and Blue Dog Coalition in a statement that affirmed their unity. “House Democrats are a diverse, robust and passionate family,” it read. “At times, there may be different perspectives on the way forward. That is a hallmark of the legislative process.” Jayapal tells me that conversations with House leadership are ongoing about how to stop her fellow Democrats from pouring fuel on Trump’s fire.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Reps. Ilhan Omar, Pramila Jayapal listen as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez speaks during a press conference announcing a bill to cancel all student debt at the Capitol in Washington, on Monday, June 24, 2019.

J. Scott Applewhite / AP

The Democratic Study Group officially ended in 1995, when newly minted House Speaker Newt Gingrich cut off the group’s public funding. But its influence had started to wither long before Gingrich pulled the plug. DSG had become a victim of its own success: By the ’80s, the group had pushed the entire party so far left that little light remained between DSG’s positions and those of the party. “The post-Vietnam, post-Watergate generation of Democrats are generally on the same page,” Julian Zelizer, a professor of congressional history at Princeton University, tells me.

The CPC may have lost a number of battles against Pelosi, but the group’s ideas appear to be winning the war. During the first round of Democratic debates in Miami last month, three of the top five 2020 hopefuls committed to Medicare for All. Pelosi, meanwhile, has been complaining that no one is paying attention to the kitchen-table topics of health care and infrastructure that she set out to achieve. She’s constantly asked in press conferences about impeachment, a topic about which the CPC has taken the lead.

The intraparty fighting over the last several weeks has threatened the gains that Jayapal and Pocan had secured through negotiating. In the annual defense spending bill—a bipartisan effort that’s expected to pass both chambers of Congress—the CPC is responsible for provisions that will block Trump from sending arms to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates without congressional approval. Just last week, the House passed a bill that will gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, a longtime progressive priority that moderates tried to kill over concerns that the amount would be too high for rural employers to sustain.

None of this will become law under a GOP-held Senate or President Trump, opening up Democrats to the very criticisms that Pelosi, Hoyer, and the party’s moderate faction had tried hard to protect against. But Zelizer takes a more generous view: The CPC, he says, offers “moral clarity” about what the Democratic Party stands for—an asset heading into 2020.

“Progressives are not radical outliers who don’t understand politics,” he says. “They are right in that the clarity of their ideas and thinking boldly about every issue, from policy to accountability, is what a party needs. That’s essential because, if you don’t have that, parties just wither and they’re not about much, and it’s hard to build a coalition and majority around not much.”

The speaker may seem like a drag on the CPC’s ambition, but “Pelosi is dealing with real votes and she’s trying to keep this majority intact,” Zelizer says. “Those are not imagined pressures. If there was a clear path for her to see a Green New Deal enacted instantly or some version of Medicare for All, my guess is she’d take it. Both have genuine concerns and challenges. I don’t know which is better, but they need each other.”