Mother Jones illustration; Alejandro Davila Fragoso/Earthjustice

Sharon Lavigne has lived all of her 67 years in St. James Parish, Louisiana. She can tell you about a time when the fig and pecan trees in her neighborhood produced plenty to eat and sell, and when her grandfather caught fish and shrimp in the Mississippi River. The land and the water surrounding it wasn’t always poison.

Today, her community is part of the 85-mile stretch along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where more than 100 petrochemical plants and refineries dot the shore. The area has been dubbed “Cancer Alley” for the prevalence of cancer among its residents, a concern that was mostly anecdotal until 2014, when the Environmental Protection Agency confirmed the region’s higher cancer risk from air toxicity in its National Air Toxics Assessment. Lavigne has lost neighbors to cancer and other ailments whose likelihood increased because of all the toxins. She too suffers from liver damage and other medical issues, including aluminum exposure.

In early 2018, when Lavigne learned that Formosa Plastics Group, a Taiwanese supplier of plastic resins and petrochemicals, had announced that St. James Parish would be the site for a massive project that would create 14 chemical plants, she says she asked God for advice. “Do I need to sell my home? He said no. I said, ‘Do I need to sell my land, the land that You gave me?’ He said no.”

“God told me to fight,” she continues. “And I’ve been fighting ever since. I’ve been going in the fast lane.”

Sharon Lavigne (left) at a RISE St. James meeting.

Alejandro Davila Fragoso/Earthjustice

The stakes for Lavigne are high. If Formosa succeeds in building its new complex at the proposed site in St. James Parish’s 5th District, there will be additional pollutants within about a mile of her house, several churches, and an elementary school. The population of St. James Parish as a whole is about 50 percent black and 49 percent white, but more than 80 percent of residents in the parish’s 5th District are black.

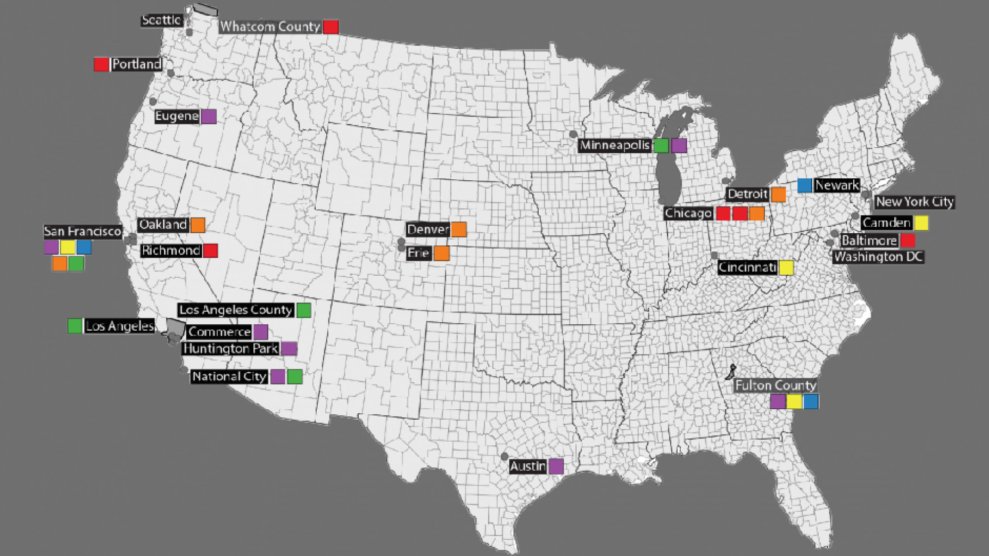

The fact that the Formosa plant would be located there follows a broader pattern in the United States: People of color, especially black people, are much more likely than white people to live near polluters. A 2018 report by EPA scientists showed the burden from pollution for those in poverty was 1.35 times higher than for the overall US population, and for black Americans specifically, the burden was even greater, 1.54 times higher than that of the overall population. The fight against Formosa is part of a long line of environmental justice battles in which communities most affected by environmental contamination and sources of pollution demand action from those in power.

Lavigne realized that to stop the Formosa plant from going forward, she would need to bring together residents, and one of the best ways to mobilize the community was through local churches. In October 2018, she invited friends and neighbors to her home for the first meeting of a new organization called RISE St. James. At that meeting, she explained what Formosa was planning in their community. Since then, around 20 people have joined and around 100 have become involved in the effort, attending meetings or protests. Their goal is a moratorium on future petrochemical plants in the fourth and fifth districts of St. James Parish.

“A project of this magnitude takes years of planning and preparation,” Janile Parks, director of community and government relations at FG LA, the Formosa subsidiary in charge of the project, said in a statement. “FG has talked with hundreds of St. James Parish citizens who support or do not oppose our proposed facility, and we remain committed to listening to community questions and concerns.”

As I wrote in CityLab, local zoning codes and land-use policies have historically enforced segregation and allowed for pollution sources to concentrate in black communities. St. James Parish changed the category used for its 4th and 5th Districts from “Residential” to “Residential/Future Industrial” in its 2014 land use plan. RISE St. James and an allied group called the Louisiana Bucket Brigade drew attention to the 2014 land use plan in a report called “A Plan Without People,” released earlier this summer. “The 2014 land use plan stoked the fire of petrochemical planning in the fourth and fifth district,” says urban planner and report co-author Justin Kray. In 2018, the parish amended this designation in part of the 5th District to allow for future residential growth, but the council was not willing to reconsider the permits they had approved before the amendments were drawn up.

Even while Lavigne was organizing, however, the process to make the plant a reality was moving forward. In October 2018, the St. James Parish Planning Commission approved Formosa’s land use application, a decision RISE St. James appealed. The appeal moved the decision to the St. James Parish Council. The council denied the appeal and in January 2019, the St. James Parish council granted Formosa the key land use approval.

Now, Formosa needs 15 air-quality permits from the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ). Members of RISE St. James have rallied against the parish council’s decision and have shifted their focus to LDEQ, urging as many people as possible to send letters to LDEQ, which sought public comment on whether to issue the air permits needed for the project. According to LDEQ public records, individuals throughout the state and across the country have heeded that call. “We spilled our guts out to them,” Lavigne says.

The public comment period ended on August 12, but even if LDEQ decides to grant Formosa the permits required, the fight will likely continue. The next step is to appeal LDEQ’s decision in court by filing a petition for judicial review against the agency. (LDEQ does not comment on pending permit applications.) The environmental law organization Earthjustice has been representing RISE St. James and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade since the fall of 2018 in the battle against the proposed petrochemical complex.

“The fight against Formosa is part of a broader effort to stop the state from green-lighting yet another major polluter in the historically African American communities of St. James Parish,” says Earthjustice staff attorney Corinne Van Dalen. “While the parish council is responsible for making this community a sacrifice zone, the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality has the duty as a public trustee to protect the community from environmental harm.”

Clyde Cooper has lived in St. James Parish his whole life and now represents the 5th District in the Parish Council. He empathizes with the health concerns raised by RISE St. James, he says, and he supports the moratorium for the entire parish until a detailed study is conducted to further understand the health impact of local industry on parish residents. He acknowledges that the moratorium is unlikely to be approved under the current parish leadership, but anticipates the potential for change after to the upcoming parish election in October, since at least a couple of the current council members are stepping down. The only reason he voted yes on the Formosa proposal, he says, was because he didn’t have the support from the rest of the council to block it.

One of the problems in fighting the proposal has been the deep ties Parish Council members have to industry. The St. James Parish website notes that Timothy P. Roussel, the parish president, has more than 40 years of industrial experience. (Roussel did not respond to requests for comment.) “They always vote with the plant, with the pipeline,” Cooper says. “They’re not against it because they’re a part of it…They don’t have a heart for these people.”

The Formosa complex would devastate more than 100 acres of wetlands, according to Earthjustice. Since wetlands are natural flood protection, the complex would worsen flooding and, in the event of a natural disaster, the risk of a chemical spill would be increased. “It’s a huge worry for communities we represent,” says Earthjustice staff attorney Michael Brown, “that there would be a second disaster.”

At a public hearing the state held for the Formosa complex last month, rows of attendees raised signs with the messages “5TH DISTRICT LIVES MATTER” and “ST. JAMES IS OUR HOME NO FORMOSA.” A video from the hearing shows a room packed with people listening to St. James resident Doris Sutherland explain how the chemical plants in the area have already damaged the area they all call home. “Before all of these plants came around, we were a thriving community,” Sutherland said at the hearing. “We don’t have nothing anymore. We don’t even have the birds that fly around us like they used to. We had hummingbirds. We had everything.”

Louisiana Bucket Brigade Director Anne Rolfes recalls that the hearing ended with a young woman singing “Hit the Road Jack.” During our phone call at the end of July, she sang the lyrics to me, “Hit the road Jack, and don’t you come back. No more, no more, no more, no more.”

Doris Sutherland spoke last week at the Formosa hearing about the destruction years of petrochemical abuse has wrought on the communities of the river parishes. #StopFormosa pic.twitter.com/tCkgBw0HIj

— LA Bucket Brigade (@labucketbrigade) July 17, 2019

Lavigne sees a fundamental problem underlying the Formosa complex in St. James. “They don’t care about our lives,” Lavigne says. “I blame the government for not explaining to the people what they’re putting in the community.”