Earlier this year, federal investigators began requesting corporate documents and questioning staff at American Media Inc., the company run by Donald Trump’s longtime friend David Pecker, about a special issue of the National Enquirer it produced that lavished praise on Saudi Arabia and its controversial leader, Mohammed bin Salman, according to two sources with direct knowledge of the investigation. Gathering evidence through at least June and working at the direction of prosecutors from the Southern District of New York, FBI agents zeroed in on the circumstances behind the magazine’s publication and, according to one of the sources, whether AMI had engaged in illegal influence peddling on behalf of a foreign power.

Both AMI and the SDNY declined to comment on the investigation, including whether it remains ongoing.

This probe came amid a lurid controversy involving AMI, which until recently owned the National Enquirer, and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. In February, Bezos accused the National Enquirer and AMI of trying to extort him over compromising photos he allegedly exchanged with his girlfriend. Gavin de Becker, a veteran private investigator working for Bezos, soon made a related charge: Saudi Arabia had swiped “private information” from the billionaire’s phone and was “in league” with the Enquirer to bring down Bezos. After de Becker went public with this allegation, in late March, FBI agents began interviewing AMI employees over the company’s relationship with Saudi Arabia. The Saudis, the Bezos camp contended, had targeted the billionaire out of revenge: Bezos owns the Washington Post, where relentless coverage of the grisly death of its columnist, Jamal Khashoggi, had enraged the Saudi Crown Prince commonly known as MBS, who was implicated in ordering Khashoggi’s murder. For AMI, the motive was different, according to this narrative: Pecker was purportedly trying to cultivate business ties to the cloistered kingdom and was using his publication to target a mutual enemy of MBS and President Trump.

The Saudi influence probe could have profound implications for AMI, according to former federal prosecutors, because it threatens to undo a deal the company struck last year with the Justice Department over its role in the hush-money case that resulted in campaign finance charges against Donald Trump’s former lawyer and fixer, Michael Cohen, who is serving three years in prison for that and other crimes. AMI agreed to cooperate fully with investigators and in return received immunity from prosecution. Yet that deal could be tossed out if AMI was suspected of engaging in other wrongdoing.

The story of how AMI came under scrutiny by the feds as a possible agent of Saudi influence is a dizzying saga of Trumpian proportions, featuring a cast of characters that includes the world’s richest man, a Saudi leader who has forged deep ties to the Trump administration, and an embattled media baron with a reputation for using his flagship tabloid to protect his allies and punish his enemies.

The place to start this sometimes-convoluted tale is where sources say investigators have focused their inquiry: the publication of a magazine dubbed “The New Kingdom.”

The cover of “The New Kingdom,” a special edition of the National Enquirer, published March 2018, touting the reformist successes of MBS, the Saudi crown prince.

Mother Jones illustration.

Intrigue over “The New Kingdom”

The special Enquirer issue hit newsstands across the country in March 2018. The 97-page magazine portrayed MBS as a modern reformer and consisted of puff pieces so flattering they bordered on satire. “THE MOST INFLUENTIAL ARAB LEADER—TRANSFORMING THE WORLD AT 32” boasted the cover, featuring a smiling portrait of the leader. The advertisement-free issue’s opening spread contained an interview with “one of the world’s youngest financial advisers for the Middle East,” a French businessman named Kacy Grine, who the magazine described as a longtime intermediary between Saudi businesses and the West, and an adviser to a member of the Saudi royal family. In the interview, Grine said that Saudi Arabia was on the cusp of a business revolution, poised to lead a “United Arabic Market” that “could be positioned between China and Europe.” And he praised MBS for overhauling the kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund.

Grine is pictured in the magazine standing next to a grinning President Donald Trump in the Oval Office. The photograph was taken during a July 17, 2017, visit to the White House, during which Grine, David Pecker, and top AMI executive Dylan Howard met with Trump and, briefly, with his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, who oversees the administration’s Middle East peace initiatives. The sit-down came as Pecker sought to do business in Saudi Arabia, where all aspects of commerce are tightly controlled by the royal family. The New York Times reported that Pecker and Grine’s audience with Trump, which included a dinner, conveyed an important message to the Saudis: Pecker possessed Washington clout and had Trump’s “unofficial seal of approval.” (“The entire conversation was social,” an AMI spokesperson told the Times, “with the exception of a couple very brief mentions of current events.”)

French business leader Kacy Grine appears in this 2017 photo in “The New Kingdom,” a special edition of the National Enquirer.

Mother Jones illustration.

Two months later, Pecker jetted to Saudi Arabia, where he and Grine met with MBS to discuss possible deals, including the expansion of Pecker’s Mr. Olympia bodybuilding competition into Saudi Arabia and North Africa, according to the Wall Street Journal.

The following spring, AMI published “The New Kingdom.” The 200,000-run edition came out shortly before MBS embarked on a publicity tour of the United States aimed at favorably shaping Western opinion about the Saudi prince, who had recently supplanted his cousin as heir to the Saudi throne in what critics have described as a violent power grab in which rival royals were jailed and tortured.

The release of the magazine quickly raised suspicions that it had been commissioned by Saudi Arabia, perhaps by MBS himself. But, after the Daily Beast inquired about the publication, Saudi embassy officials denied any government involvement in its production. Yet the Associated Press subsequently reported that digital copies originating from AMI had been “quietly shared with officials at the Saudi Embassy in Washington almost three weeks before its publication.” An AMI spokesperson insisted to the AP that the magazine was not funded by Saudi Arabia and that the kingdom had played no role in its production: “Absolutely not.” (The Saudi Embassy in Washington did not respond to interview requests.)

The AP story noted that if Saudi Arabia had financed the publication—directly or through an intermediary—AMI had potentially violated the Foreign Agents Registration Act, a law designed to protect American policy from secret foreign influence campaigns by requiring lobbyists on the payroll of foreign governments or promoting foreign interests to register with the Justice Department. After the AP scoop, AMI quietly sought an opinion from the Justice Department about whether it should retroactively register under FARA.

In July 2018, the head of the Justice Department’s FARA unit responded, telling AMI that, based on the information the company had provided, it did not need to register as a foreign agent. But she warned AMI that this judgment could change if facts emerged that “are different in any way from those depicted in your submission.” The letter referenced earlier correspondence with AMI in which the company contradicted its public claims that it had not sought input from Saudi Arabia regarding the magazine, acknowledging that AMI had given an adviser to the kingdom a draft of the publication and subsequently followed that adviser’s editorial suggestions. (The name of the adviser is redacted in the letter.)

Meanwhile, Pecker and his company faced another potential legal imbroglio. That August, Trump’s longtime lawyer and fixer, Michael Cohen, pleaded guilty to campaign finance charges related to his role during the 2016 presidential election in helping Trump cover up alleged affairs with porn star Stormy Daniels and a former Playboy model named Karen McDougal. Pecker and Howard, AMI’s chief content officer, had been in regular communication with the Trump campaign, according to court documents in Cohen’s case, and were deeply involved in the hush-money effort. At Cohen’s urging, AMI had paid McDougal $150,000 for the rights to her story in August 2016, three months before the election, to prevent her from taking her tale to other publications—a strategy known as “catch and kill.”

Implicated in potential criminal activity, Pecker and Howard pledged to cooperate with the Southern District of New York’s investigation into wrongdoing by Cohen and, potentially, by Trump, who was named as “Individual 1” in Cohen’s indictment. (When he pleaded guilty, Cohen told the court that he had acted “for the benefit of, at the direction of, and in coordination with ‘Individual 1’. And for the record: ‘Individual 1’ is Donald J. Trump.”)

In exchange for Pecker’s and Howard’s assistance, the SDNY entered into an agreement with AMI that it would not prosecute the company for possible campaign finance violations. There was a catch: It stipulated that the SDNY would rescind the deal if AMI committed any crimes after signing it or if federal prosecutors determined the company or its representatives had provided “false, incomplete, or misleading testimony or information.” If the deal were breached, AMI would be “subject to prosecution for any federal criminal violation of which the Office has knowledge, including perjury or obstruction of justice.”

Within five months of inking that agreement, AMI was at risk of losing its immunity after immersing itself in a new, soap-operatic scandal involving allegations of extortion, betrayal, and an alleged Saudi scheme to get even with Jeff Bezos.

President Trump greets MBS in a photo featured in AMI’s “The New Kingdom.”

Mother Jones illustration.

The “Below the Belt Selfie”

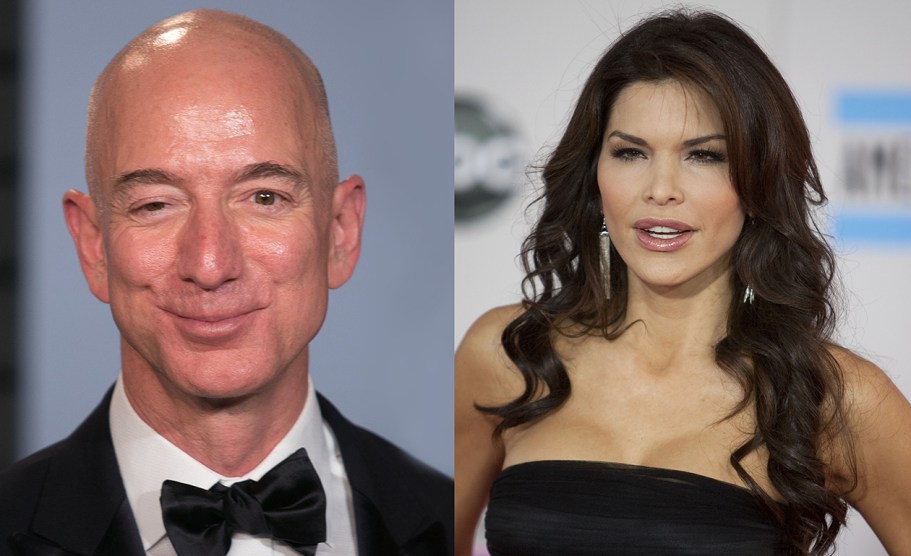

In its January 24, 2019 issue, which was available for purchase on newsstands on January 10, the National Enquirer reported that Bezos was having an affair with a former Los Angeles television host named Lauren Sanchez, disclosing flirty messages Bezos had texted her. Bezos and his wife of 25 years, MacKenzie, announced their plans to divorce the day before the Enquirer bombshell appeared in print. Their eventual $38 billion divorce settlement was the largest in history.

Bezos turned to Gavin de Becker, a well-known private investigator with a lengthy roster of famous clients, to determine how his messages had wound up in the Enquirer‘s hands. And in a February 7 post on Medium, Bezos struck back at AMI and David Pecker. Accusing the company of “extortion and blackmail,” he revealed that AMI officials had threatened to publish more text messages, as well as racy photos, including what an AMI executive described in an email to an attorney for Bezos as a “below the belt selfie,” if he and de Becker did not call off their investigation and publicly state that they had “no knowledge or basis for suggesting that AMI’s coverage was politically motivated or influenced by political forces.” (An AMI representative contended in an interview with ABC News that the company’s communications with Bezos’ team about the photos represented a negotiation, not an attempt at coercion.)

In his post, Bezos hinted at a possible Saudi connection to this scandal. He raised Pecker’s curious dealings with the kingdom and suggested that de Becker’s inquiry was delving into AMI’s Saudi ties. “Several days ago,” Bezos wrote, “an AMI leader advised us that Mr. Pecker is ‘apoplectic’ about our investigation. For reasons still to be better understood, the Saudi angle seems to hit a particularly sensitive nerve.”

The Daily Beast subsequently reported that the source of the salacious messages was Lauren Sanchez’s brother, Michael Sanchez, a Hollywood talent agent. According to the Wall Street Journal, the Enquirer paid him $200,000 for the texts. Sanchez denied to the Washington Post that he revealed his sister’s relationship with Bezos to the Enquirer; he declined to comment on the Wall Street Journal report beyond denying that he provided to AMI “the many penis selfies.” Sanchez declined to comment for this story.

According to de Becker, Michael Sanchez was no more than a bit player in this drama. On March 30, he penned an article for the Daily Beast in which he likened Sanchez to “a low-level Watergate burglar” and accused Saudi Arabia of orchestrating the attack on Bezos as part of an ongoing campaign to “harm” the billionaire in retaliation for the Post‘s aggressive coverage of Khashoggi’s murder. “Our investigators and several experts concluded with high confidence that the Saudis had access to Bezos’ phone, and gained private information,” de Becker wrote. “My results have been turned over to federal officials.” De Becker declined to comment for this story.

After Bezos accused AMI of extortion, the SDNY began examining the allegations and whether AMI had violated its non-prosecution agreement, the AP reported. Shortly after de Becker published his allegations, FBI agents began grilling AMI staffers over the company’s Saudi dealings, according to the two sources familiar with the federal investigation. This phase of the probe, said one of the sources, focused on whether AMI had violated the Foreign Agents Registration Act.

Meanwhile, CNN reported in April that Bezos was “scheduled” to meet with federal prosecutors who were seeking access to his personal devices to assess the hacking claims. Amazon did not respond to questions from Mother Jones.

On Sunday, Fox News reported that the SDNY had convened a grand jury to gather evidence related to Saudi involvement in accessing Bezos’ messages, as well as Bezos’ extortion allegations against AMI. Mother Jones could not independently confirm the Fox report.

Former federal prosecutors say that if investigators are scrutinizing AMI for possible FARA violations, extortion, or other crimes, the company should be worried that its non-prosecution deal for the hush-money payment is in serious jeopardy.

“If you’re a party to a non-prosecution agreement, you should expect you should be investigated if there’s any hint of wrongdoing,” says Renato Mariotti, a former federal prosecutor in Chicago. “If there are any allegations or suspicions about AMI, there are going to be investigations.”

If prosecutors discover any wrongdoing, “it would be a pretty clear-cut case that they are in violation of the agreement, which could mean getting charged for the conduct we’re giving you immunity for,” says Mimi Rocah, who from 2001 to 2017 served as an assistant US attorney with the SDNY.

Rocah adds that prosecutors don’t need to bring new charges to nullify the immunity deal. The standard, she notes, is, “Did they do something in violation of the law, with some evidence? But it’s not about whether they can win it in court.”

Last month, federal prosecutors told a judge in New York that they had concluded their investigation into Trump’s hush-money payoffs and did not anticipate bringing more charges. But it’s unclear what this means in connection with the SDNY’s AMI inquiry and the possible breach of its non-prosecution deal. (State prosecutors in New York recently launched their own investigation into the hush-money payments.)

As controversy and legal problems have engulfed AMI, the company has faltered. Bloomberg reported earlier this year that the debt-riddled company had a negative net worth. In April, Pecker sold his signature tabloid for $100 million. The Enquirer, an unapologetic peddler of scandal, had become a source of it, featuring in a sordid and too-strange-to-be-true tale of its own creation. And the story, as far as Pecker and the Saudis are concerned, does not appear to be over yet.