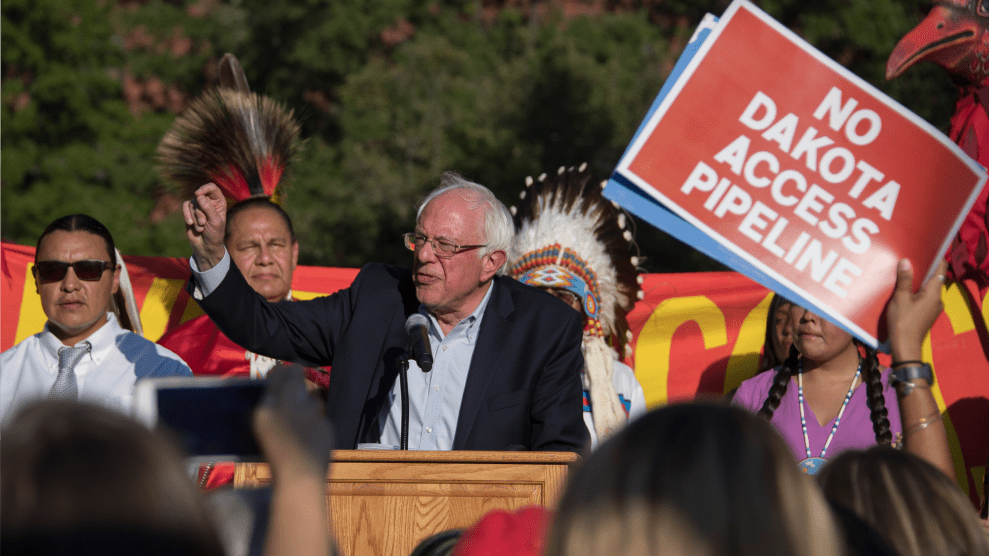

Sen. Bernie Sanders speaks at a Native American–led rally against the Dakota Access pipeline in September 2016.Jim Watson/Getty

At the Native American Presidential Forum last Monday morning, Sen. Elizabeth Warren made headlines by finally apologizing for claiming Cherokee heritage. “I know that I have made mistakes,” she said onstage before a crowd of indigenous leaders and voters. “I am sorry for harm I have caused.”

Though the apology received mixed reviews, with some Cherokees saying it did not remedy the harm caused, the statement, and the forum itself, which was held in Sioux City, Iowa, signals something important about this presidential election: Candidates are finally courting Native voters.

Indigenous people in the United States did not have the right to vote until they were made citizens in 1924, decades after being excluded from the 14th Amendment, which promised citizenship to “all persons” born on US soil. Indigenous voting rights weren’t guaranteed in all 50 states until 1962, when Utah became the last state to grant suffrage to Natives living on reservations.

Even today, there are insidious barriers that keep Natives from voting. As my colleague Tim Murphy reported last year, many who live on Indian reservations have to travel great distances to reach polling places. Mail service is limited. And many Natives on reservations lack a residential address—something Republicans in North Dakota took advantage of in 2013 when they tightened their voter ID restrictions after Democrat Heidi Heitkamp won a Senate seat, thanks, in part, to Native voters.

Indigenous groups, including Four Directions and the Native American Rights Fund (both of which co-sponsored the presidential forum) have used litigation to work toward equal access at the ballot box. In 2004, Four Directions negotiated with county officials in South Dakota to create satellite voting offices near reservations, allowing more Natives to vote early. They later won a lawsuit to expand the early voting period on two Lakota reservations, whose residents had fewer days to vote than the rest of the state population. Through similar lawsuits, the group won satellite voting offices on reservations in Montana in 2013, and in Nevada in 2016. Four Directions has now turned its sights on Arizona, while continuing to organize on reservations in other states to get voters out to the polls.

As a result of these efforts, Native are becoming an increasingly influential voting bloc. OJ Semans Sr., co-executive director of Four Directions and member of the Rosebud Sioux, says that some areas where they’ve expanded access, like South Dakota reservations, have seen Native voter turnout double. Similarly, a Claremont Graduate University study on Nevada reservations found a jump in voter turnout after the state opened satellite offices in 2016. Despite North Dakota’s new voter ID laws, the state’s Native turnout surged in 2018.

Natives are now winning more representation in states like Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Alaska, which each have a population that is at least 10 percent indigenous. In 2018, Deb Haaland and Sharice Davids became the first two Native women ever elected to Congress.

The US indigenous population is growing at a faster rate than the rest of the general population, meaning that as roadblocks to their voting rights continue to be dismantled, their role in elections will likely expand. Natives are becoming a “significant demographic” in key presidential battleground states, says Julian Brave NoiseCat, a journalist who belongs to the Secwepemc and St’at’imc Nations. “If you’re hoping to win Nevada, Arizona, Michigan, or Minnesota, the Native vote is not inconsequential.”

The indigenous-led movements at Standing Rock, Bears Ears, and Mauna Kea have also raised national awareness about Native issues and the political power of Native organizing.

“We are seeing a generational and historic shift in the power and representation of Native people in national politics,” says NoiseCat. “The indicator of our success so far has been the election of Representatives Deb Haaland and Sharice Davids. But the trends underlying that are broader and more durable than just the election of those two.”

Democratic candidates are apparently taking notice of these trends: Ten of them, including frontrunners like Sen. Warren, Sen. Bernie Sanders, and Sen. Kamala Harris, turned up in Iowa to attend the forum last week, where they were addressed by a panel of tribal leaders and Native youth. Treaty rights, tribal sovereignty, and federal program funding were three of the most discussed issues.

In the process of securing the lands that became the United States, the federal government ratified hundreds of treaties with Native tribes, many of which are still legally binding. Yet the terms of those treaties—from promising large swaths of land to providing services like education, health care, and housing—have often been outright ignored. Funding for federal agencies that fulfill treaty obligations, like the Indian Health Service and the Bureau of Indian Education, is often on the chopping block. Many such services went unfunded during the December government shutdown.

For some, Warren was a standout at the forum. “She demonstrated a level of mastery of a complicated set of issues that are not mastered by most folks,” says NoiseCat, who praised the senator for her ability to articulate specific plans and policies. Meanwhile, Sanders took the stage to a standing ovation, demonstrating his continued popularity with Native voters: He was early in vocalizing his opposition to the Dakota Access pipeline, and he worked with an indigenous advisor during his 2016 bid for the Democratic nomination.

Both Warren and Sanders, as well as fellow Democratic candidates Julián Castro and Marianne Williamson, released substantial pro-indigenous platforms ahead of the forum, focusing on policies like expanding tribal sovereignty and funding Native programs more consistently.

Given their history of betrayal by the US government, indigenous nations aren’t quick to trust that the talk they hear from politicians will turn to action. As Simon Moya-Smith, an Oglala Lakota and Chicano journalist, stated in a poignant op-ed, “Candidates are courting the Native vote because of the stakes in the primary race and in the general election, not necessarily because of a genuine interest.”

But Karen Diver, who is Lake Superior Chippewa and served as Native American Affairs adviser to President Obama, thinks there’s real potential for change. “During the Obama administration we saw what was possible when tribes actually had an ally in the White House,” she says. “The presidency sets the tone for how federal agencies interact with tribes.”

She thinks it’s important that candidates are now representing Native issues in their platforms. “If the candidate doesn’t care, you continue to be invisible,” she says. “Not seeing themselves as invisible anymore could motivate Native voters to come out and recognize their power.” And that could make a big difference in 2020.