Detric Linner, 41, is considering voting for the first time. Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project

This article was originally published by The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

Most Sundays, Clint Williams attends service at one of the biggest churches in New Orleans. In the pews he sometimes finds himself sitting shoulder to shoulder with the city’s black elected officials. Over the years many have asked for his support.

“Politicians ask me: ‘Are you voting for me?’ And I’d just say, ‘yeah, I am working on it,’” Williams said.

But Williams, 58, has never voted. He’s been on parole for the past 30 years, which, until March, made him ineligible to choose who will represent him in public office. If not for the law change, Williams would have lost the right to vote until he was nearly 80 years old. His parole ends in 2040.

Williams and nearly 37,000 Louisianians who have recently had their voting rights restored by the state legislature are joining a potential wave of new voters from across the country. Last year, Florida elected to restore voting rights to nearly 1.5 million people with felony convictions. And, as of July 1, nearly 77,000 formerly incarcerated people in Nevada will be able to vote in the next election.

The influx of new voters could shape upcoming elections in these states as well as the presidential race in 2020. Florida and Nevada, both increasingly purple swing states, are important prizes to secure an Electoral College victory. While little is known about the political leanings of the formerly incarcerated, many political observers assume they would vote for Democrats. For one, black adults are four times more likely to be barred from voting because of felony disenfranchisement laws, according to the Sentencing Project. And black voters have consistently favored Democrats.

But these assumptions could be overblown. The formerly incarcerated must overcome daunting hurdles, both personal and administrative, in order to vote. In Florida, for example, the legislature required the newly-eligible voters to pay outstanding fines and fees before registering, which critics say is akin to a poll tax. In Louisiana, many of these potential voters are consumed by the struggle to rebuild their own lives after prison. They must also combat the apathy born of their ordeals: In interviews, several formerly incarcerated people said they were not sure that elected officials can make a difference in their lives.

With the voter registration deadline in Louisiana looming for the upcoming gubernatorial primary in October, community organizers are working overtime to reach as many newly eligible voters as possible. Under the new law, people on probation and people who have been on supervision for five years after being released from prison are able to get their voting rights restored. But the state will not automatically inform people who are affected. So the organizers have run ads on social media, put up posters in probation and parole offices, knocked on doors in minority neighborhoods, and appeared on local news stations. They’ve even held an eight-city bus tour, with the help of the nonprofit Black Voters Matter Fund, to raise awareness about the change in the law. But turnout was low: Only a handful of people showed up to register.

Checo Yancy, 73, director of voter education with VOTE, the community organization spearheading the voter registration effort, says Louisiana’s secretary of state could be doing much more to inform the new voters and to make the registration process less cumbersome. But for now, voter registration requires two steps. First, the newly enfranchised must pick up a letter of eligibility from their probation or parole officer. Then they must take the letter to the registrar’s office, along with valid ID. A spokesperson for Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Still, Yancy is undeterred. He once faced a life sentence for kidnapping and other charges before receiving a sentence commutation from the governor in 1995. Ultimately, he spent 20 years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary where he got his start as a political organizer working

to improve prison conditions. And he was instrumental in getting the voting law passed last year. In October, he will cast a ballot for the first time in nearly 40 years, and he is optimistic that many of the 37,000 newly eligible voters will head to the voting booth, too.

“We have come from out of prison to do all this, and we are doing it,” he said.

The Marshall Project spoke with several formerly incarcerated people in Louisiana about how they feel about having the right to vote again and whether they plan to exercise it.

Lionel Paul Dugas, 45, New Iberia

Lionel Dugas, of New Iberia, La., didn’t realize that for the past three years he’s been eligible to vote since he is not on parole.

Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project.

Prison has cost Lionel Dugas more than he can count. His job working on an oil rig was the first thing to go. After a few years in prison, his teeth began falling out. Often, he says, the prison medical staff only gave him aspirin to dull the pain radiating through his jaw. Then, after years of physical labor and limited medical care, the feeling in his hands began to fade.

“State prisons will eat you inside out,” he said. “When I say I came out with nothing, I mean I really didn’t have nothing.”

Dugas spent eight years in prison for theft and forgery. In the three years since he has been back home, he’s struggled to rebuild the life he once had. Many formerly incarcerated people say the first few years after prison are the hardest. Landlords are reluctant to rent to them, and job options are often limited. Many struggle to meet their most basic needs.

To get by, Dugas works odd jobs as a painter and a carpenter. From the work he’s able to cobble together, he makes about $1,000 a month. After he pays rent, there’s little left for anything else. To make matters worse, Dugas’s driver’s license was suspended for failing to pay outstanding child support. Without a car, he says, it’s hard to get to work. Without work, it’s hard to pay off his debts.

“I struggle so much,” he said.

So on a blistering Monday in July, Dugas came to a rally at Philadelphia Christian Church in Lafayette looking for a fresh start. He’d been attending the church’s programming for newly released prisoners and heard about a rally to register formerly incarcerated people to vote. Dugas didn’t realize that for the past three years he’s been eligible to vote since he is not on parole. He thought a felony conviction barred him indefinitely. Organizers are using the law change as an opportunity to get people like Dugas to the polls.

Dugas admits he doesn’t know enough about politics to understand the differences between Democrats, Republicans or independents. He isn’t sure who he will vote for in the upcoming election, but he wants the nominees to understand the challenges he has faced as a result of his incarceration.

Voting won’t restore the feeling in his hands, pay his debts, or get him back on the road. The benefits are mostly spiritual, he says. Registering to vote has given him a sense that he is welcomed back in society.

“These doors are starting to open for me, and it’s scary to walk through doors that have never been open,” he said. “But I am still on the bridge, and I am taking little baby steps.”

Charles Blue, 42, Shreveport

Charles Blue, of Shreveport, La., believes it’s important for people with criminal records to make their voices heard at the ballot box.

Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project.

For the past several months, Charles Blue has been working to register formerly incarcerated people to vote. Voting has always been important to him, and the five years he spent in prison for theft intensified his longing.

“When something is taken away from you, you regret the fact that you want to use it but you can’t,” he said. “So when it’s restored, it’s very important.”

But when he shows up to soup kitchens and churches trying to help people get their rights back, he is often met with indifference.

“You are trying to connect with people who at so many points don’t see the value,” he said. “They are more concerned with finding a job and trying to find a place to stay.”

He tries to cut through their resignation by drawing a direct line between their lives and the decisions that are made in Washington and in Baton Rouge, the state capital.

“All this boils down to one thing,” he said. “At that poll, in that voting booth, at that machine when you push that button. That representative that you are sending up to the state capital or to Washington, D.C., needs to represent your voice.”

It’s even more important for people with a criminal record to vote, he says. For years, Louisiana held the dubious distinction of being America’s mass incarceration capital. The state is working to roll back many of the practices that have filled up its prisons. But harsh sentences have already devastated the black community, Blue says. Over the years, he has watched many members of his community go to prison for years because of minor crimes. Under its habitual offender law, the state imposed tough sentences for repeat offenses.

“A lot of people didn’t understand what they were going to do with it until it actually affected them,” he said, arguing why voters could make their opposition to such tough-on-crime laws known at the ballot box.

These experiences have instilled in him a sense of pragmatism about politics. More than party affiliation, he says, he’ll base his vote on what would help him and his community thrive. He challenges the notion that the wave of potential new voters will automatically support Democrats.

“I want sustainable housing and better education,” he said. “If a Republican candidate is not saying the right things, but he is doing the right things and is putting forth a plan to help us get to a better point in life, then I can support him.”

Detric Linner, 41, Shreveport

Detric Linner’s interactions with the criminal justice system have shaped his politics.

Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project.

In his teens, Detric Linner was in and out of jail. By the time President Barack Obama took office in 2009, Linner was 30 and serving a 25-year prison sentence for selling drugs.

At the time, many black Americans hoped that the nation’s first black president would put their issues at the center of the national political agenda. But in hindsight, Linner says he felt overlooked.

“Obama did nothing for me,” he said.

While he points out that Obama did make some positive changes, he says the former president did not go far enough to make criminal justice a priority.

“He’s a black man, and he was there for eight years,” he said. “He knew black people were the most highly incarcerated race in America. I feel like this should have been one of the issues he was attacking first before anything.”

Like many formerly incarcerated people, Linner’s entanglement with the criminal justice system has shaped his politics. Voting wasn’t a priority during the chaotic years before he went to prison. And he could not vote while incarcerated. Now, as he considers voting for the first time, he’s inclined to defer to a higher power.

“I feel like [politicians] all have their own personal agendas they are trying to push,” he said. “I know it’s important to vote for somebody. But, I just leave it in God’s hand.”

Outside of the probation and parole office in Shreveport, Linner said he has more pressing issues to address. He will be on parole until 2033, and will be required to check in with his parole officer once a month. To stay out of prison, he must comply with a long list of rules.

“Right now, I am just trying to be obedient to the laws so I can stay free,” he said. “They say if you do good for a couple years then they’ll let you off early.”

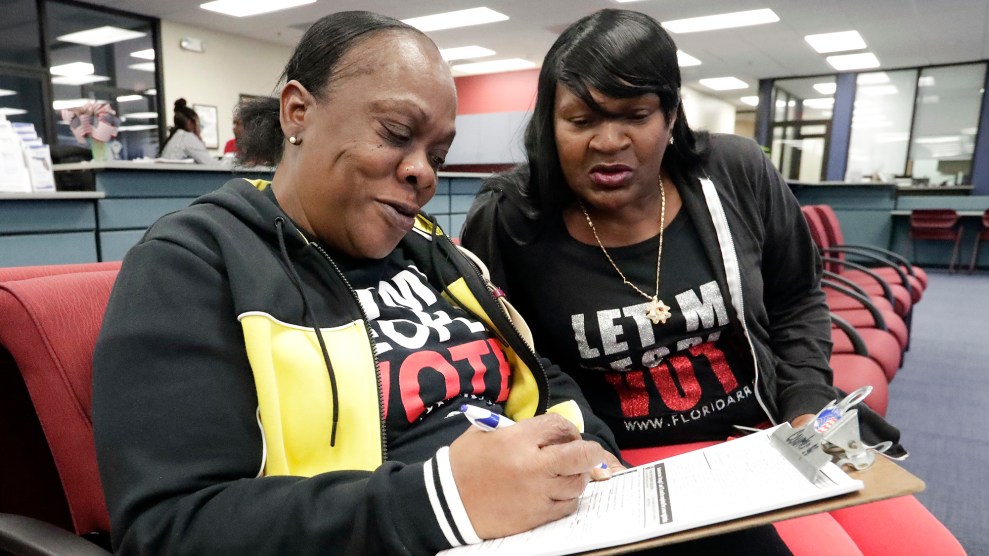

Patrice Sparks, 36, Shreveport

In March, Patrice Sparks became eligible to vote while still on probation.

Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project.

Two weeks after Patrice Sparks returned home from a brief stint in jail, she got a letter in the mail saying her voting rights were being terminated. Sparks was sentenced to two years’ probation after shooting a gun at an ex-boyfriend she says was trying to kill her.

Sparks has been a registered Democrat for as long as she can remember. She even voted for Obama twice. She knew that probation would mean check-ins with an officer, drug tests, and curfews, but she says no one told her that it also meant losing the right to participate in elections.

When the law changed in March, making Sparks eligible to vote while still on probation, she says she never received a letter informing her that her rights had been restored. Sparks says her probation officer has never mentioned voting. The only indication something had changed was a poster in the lobby that reads: “Don’t assume you can’t vote because you are formerly incarcerated.”

“Nobody explained anything to us,” she said. “We just got to read the sign and figure it out ourselves.”

But Sparks got lucky. A group of volunteers planned to register new voters at the probation and parole office in Shreveport on the same day Sparks needed to check in. Once she finished meeting with her officer, Sparks stopped by the volunteers’ table to fill out the voter registration paperwork.

For weeks, Sparks held onto the application before dropping it off. She knew she needed to take the papers to the registrar’s office, but the requirements of her probation filled up her schedule.

Sparks was assigned a new probation officer with roughly seven months left on her sentence. The officer asked her to take a drug test, and Sparks turned up positive for marijuana. Sparks says she had already quit smoking, and suspects the marijuana was slowly fading from her system. Now she has to report to drug class five days a week in addition to working full time.

“This class is interfering with my life,” she said. “There are other things I wanted to do, like going back to school.”

Clint Williams, 58, New Orleans

Clint Williams, of New Orleans, La., will be voting for the first time in October.

Akasha Rabut/The Marshall Project.

In October, Clint Williams plans to enter the voting booth for the first time. Now, when members of his church ask for his vote, he will finally be able to tell them yes.

Many at his church don’t know about his past or even that he’s on parole. He isn’t keen on talking about the mistakes he made over 30 years ago. Williams says he went through a wild phase after losing his parents at a young age. His mom died when he was 9 years old. A few years later, his father died, too. Without his parents around, Williams says he clung to other directionless teenagers. At 18, he went to prison for 10 years after a robbery turned fatal—the man they tied up suffocated and died.

His wild days have been behind him for years, he says. His check-ins with his parole officer have decreased to once every six months.

“He pretty much knows those days are gone,” Williams said of his parole officer. “He works with me. He’ll come on my job and people just think he is one of my clients.”

Williams doesn’t see the parole requirements as a burden. He has his freedom. He owns two small businesses. In the summer he runs a snowball stand, and he works year round as a carpenter. He sings in a men’s choir. The only nuisance, he says, is the $64 fine he must pay to probation and parole each month. The challenge of spending decades under surveillance is mostly mental, he says.

“There is nothing you can really do,” he said. “You have two options: You can be on parole or be locked up.”

Williams has made his choice, and by many measures he is living a normal life. He credits his faith for helping him weather the tough times. The men in his choir serve as a guide for the kind of life he wants to live.

“There are senators and lawyers and doctors and everyday men,” he said. “People who have been incarcerated and people who have not. I don’t want to mess up.”

Until March, the only thing missing was the ability to vote.

His work and faith have brought him into close contact with several elected officials in New Orleans. Over the years, he has been to city hall countless times to get permits and to register his businesses. Voting isn’t just political, he says, it’s personal, too.

“The mayor of New Orleans just took a picture with me at a snowball fest,” he said. “I know these people and I support them and I want my voice to matter.”