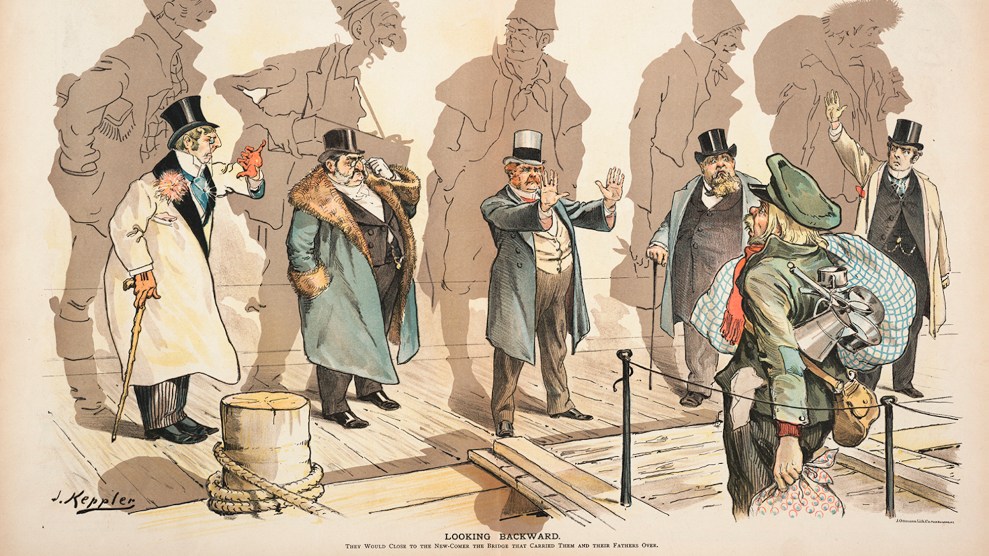

An 1893 cartoon titled "Looking Backward" depicts the irony of American immigrants turning away additional newcomers. The caption reads: "They would close to the new-comer the bridge that carried them and their fathers over."Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at the Ohio State University

In 1882, four decades before the creation of the Border Patrol, the United States established one of its first ways of keeping out poor immigrants. It didn’t require a wall or a new law enforcement agency, just a few lines of seemingly neutral legislation that directed immigration officials to block people they deemed likely to become “public charges” with financial dependence on the US government.

On Monday, the Trump administration revived the public charge rule to keep out working-class immigrants who now disproportionately come from Mexico and Central America. The new rule, which goes into effect in October, could block hundreds of thousands of immigrants from receiving green cards by making them ineligible for permanent legal status if immigration officers decide they’re likely to use modest amounts of government assistance. The plan has the potential to be the Trump administration’s most dramatic restriction on legal immigration.

The original public charge rule grew out of a nativist backlash against Irish immigrants. In later decades, it went on to target the new populations from Eastern and Southern Europe that were arriving in large numbers. The public charge rule responded to nativists’ fear that those nations were offloading their poor onto America. Now, the rule is being as a weapon in a new nativist backlash against Latinos. Having failed to get Congress to back its plan to dramatically cut the number of working-class immigrants, the administration is trying to do that on its own with this sweeping regulation. The National Immigration Law Center announced on Monday that it plans to file a lawsuit to challenge the rule.

Immigrants applying for green cards, which provide permanent legal status and a path to citizenship, are already barred from receiving most government assistance. As a result, the new rule would rarely block people from getting green cards because of benefits they’ve already used. The change is dramatic because of how much leeway it gives federal immigration authorities to turn people away: Immigrants will now be punished if officials at US Citizenship and Immigration Services decide they’re likely to use government programs like Medicaid, food stamps, and housing assistance in the future.

To figure out whether someone is likely to receive those benefits, USCIS will look at things like a person’s age, income, health, education, English language ability, and even credit score. Put simply, it’s a test of an immigrant’s wealth and privilege. Immigrants with little of either could be denied green cards.

Immigrants were previously considered public charges only if most of their income was likely to come from the government, a generous standard that allowed the vast majority of people to pass the public charge test. Now they could be denied legal residency if even a small portion of their income is likely to come from government programs. It’s unclear how many people will be denied, and a lot will depend on the specific instructions immigration officers are given about implementing the new standards.

The rule will apply to immigrants applying for green cards from within the United States. The State Department handles green card applications from people abroad, and Randy Capps, the director of research for US programs at the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute, says it seems highly likely that the State Department will move to adopt USCIS’s public charge standard.

USCIS will consider incomes above 250 percent of the federal poverty line—about $62,000 for a family of four—as a major positive factor in public charge determinations. In an analysis of the rule’s potential impact last year, the Migration Policy Institute found that 71 percent of recent legal immigrants from Mexico and Central America wouldn’t clear the 250 percent threshold, compared to 25 percent of those from India and 34 percent from Canada. Capps says the rule is line with the administration’s narrow definition of merit and its “express desire to exclude people who are not from Europe” as it mostly targets immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

The second impact of the rule is likely to come through indirect “chilling” effects, as misunderstandings and fear cause immigrants to drop out of government programs that they remain eligible for. Immigrants who already have green cards are not affected by the rule, nor will immigrants be punished for benefits used by family members who are eligible for them, Capps explains. But the Migration Policy Institute’s research shows that confusion could lead many immigrants to stop using government programs anyway. Kara Lynum, a Minnesota-based immigration attorney, wrote on Twitter that she’s already had multiple clients call to ask her if they should unenroll their US-citizen children from programs like free school lunches they remain completely eligible for.

Doug Rand, who worked to promote entrepreneurship in the Obama White House and is now the president of a technology company called Boundless that helps immigrants apply for green cards, says one of the main goals is to “scare a bunch of people [into] not using safety net programs” they remain eligible for. Having fewer immigrants using public benefits is the administration’s explicit goal: The White House announced in a press release Monday that the rule was designed to “help ensure that non-citizens in this country are self-sufficient and not a strain on public resources.”

At the White House rollout of the rule on Monday, USCIS director Ken Cuccinelli framed the rule as a simple matter of promoting “self-reliance” among immigrants. Cuccinelli was proud to note that his own Italian grandfather had brought his cousins Mario and Silvio to the United States. Trump has said he wants to end this very practice of what he calls “chain migration.”

When a reporter asked why the Latino community shouldn’t feel targeted by the rule, Cuccinelli replied, “Well, first of all, this is a 140-year-old legal structure…This is not new. The same question might have been asked when my Italian immigrant ancestors were coming.”

Cuccinelli is right. There’s nothing new about using the public charge rule to target immigrants from nations disliked by nativists. Early on, it was people like Cuccinelli’s Italians. The New York Times argued in 1887 that the public charge rule would prevent Italy from sending “monthly consignments of Neapolitan mendicants” and stop nations from improving “their average of citizenship by lowering and polluting ours.” Today, the targets are different, but it’s the same message: Send them back.