Ramon Espinosa/AP

This story was originally published by The Guardian. It appears here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The silence along the Grand Bahama highway, the only major road on the island, is foreboding, punctuated only by the occasional truck driving east. The once dense forest on either side of the road has turned to bare branches. Houses and government buildings have been reduced to their concrete foundations. Cars and small jet planes have been left crumpled wreckages by 185 mph winds. Boats washed inland by the storm surge are planted among foliage.

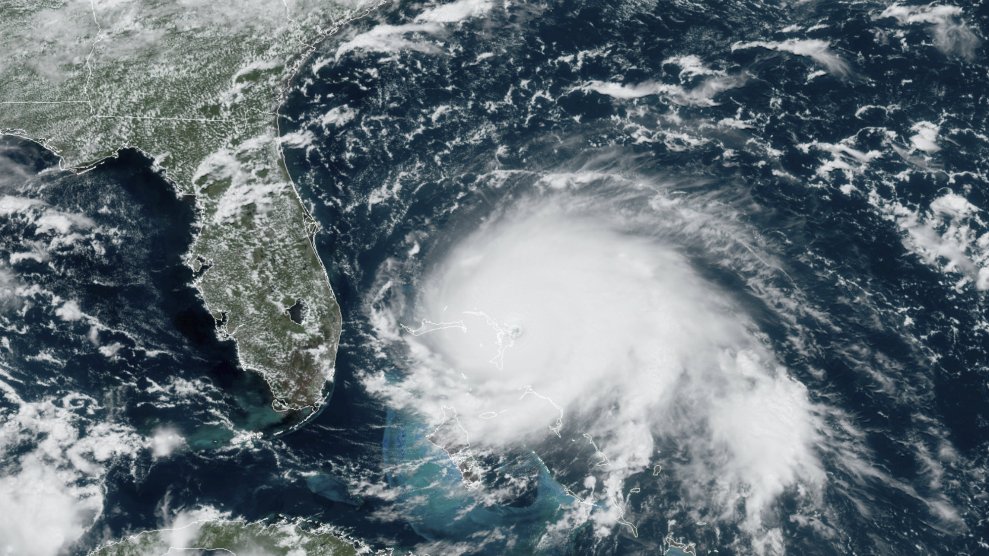

The sheer brutality of Hurricane Dorian was on display to the few people travelling back towards the worst-hit areas on Grand Bahama, a thin strip of land that is home to 50,000 people.

As a lone pick-up truck slowed to navigate the smashed tarmac ahead, Shenelle Kemp called from the back: “We have no food. No water. We’re abandoned here.”

Kemp, 45, was heading back to her home town of High Rock, in the island’s remote centre, an area mostly turned to rubble that had only been fully accessible since Thursday after Dorian ravaged Grand Bahama and the Abaco Islands in the north of the Bahamas archipelago, which is home to about 70,000 people.

As aid agencies struggled to reach the parts of the Bahamas most severely affected by the category 5 hurricane, some, like Kemp, had tried to take matters into their own hands. She was heading back to salvage what she could from a home and small business she knew had been destroyed.

The true scale of Dorian’s destruction here is still unfolding.

On Friday evening, the Bahamian prime minister, Hubert Minnis, updated the death toll to 43 but acknowledged that the number was “expected to increase significantly”.

“This is one of the stark realities we are facing in our darkest hour,” Minnis said in a statement. “The loss of life we are experiencing is catastrophic and devastating. The grief we will bear as a country begins with the families who have lost loved ones. We will meet them in this time of sorrow with open arms and walk by their sides every step of the way.”

On Abaco Island, reports indicated numerous uncollected bodies had been obscured by piles of detritus, the creeping stench alerting authorities to their location. On Grand Bahama residents told The Guardian that dozens of people remained missing, some were assumed to have been swept away by the storm.

Ishmael Laing, a 69-year-old engineer living on the island’s centre, was one of those lucky not to have his home destroyed. It sits on higher ground but was still inundated with storm water that rose to about 8 feet inside.

He watched as the winds, sometimes gusting at 220 mph, ripped off the roofs of his neighbours’ home “like they were feathers”.

And then, as the storm surge rapidly increased, he saw it “roll over” the home of a lifelong friend, Roswell, from across the street.

“He is no more. They haven’t found the body, but there was no way to survive that,” he said. “My nephew, too. He died. They found him yesterday. He got carried away with the flood. His whole building was gone.”

In the city of Freeport on Grand Bahama on Friday, hundreds lined up to try to leave the island as the Bahamian government vowed to evacuate every citizen who wanted to go. But there simply was not enough space on private boats to take everyone. There were similar, more severe scenes on Abaco Island where thousands were awaiting evacuation.

“It’s going to get crazy soon,” Serge Simon, a 39-year-old ice truck driver, told the Associated Press as he waited with his wife and two sons, five months old and four. “There’s no food, no water. There are bodies in the water. People are going to start getting sick.”

Later in the day the airport in Freeport, previously littered with debris, opened once more, meaning more aid was likely to flow into the island.

But around the same time, an international petroleum company announced that an oil terminal on the island had sustained severe damage during the storm, leading to a serious spill. The Norwegian company, Equinor, said it had not determined how much oil had leaked from its 6.75m gallon crude oil tanks, but there were no indications yet it had made it to the sea.

Phillip Smith, the executive director of the Bahamas Feeding Network, fronted efforts to deliver 20,000 meals to those most in need in Freeport. The aid had been provided by the cruise line giant Royal Caribbean earlier in the day. At present, he said, no aid had been provided directly by the government of the Bahamas, although assistance was being given by its National Emergency Management Agency (Nema).

Smith was aware of the challenges he faced in getting to the more remote parts of the island, cut off for days due to treacherous weather and impassable roads.

“Just going into the communities here is tough. Seeing kids who haven’t had a drink of water in quite a while, it’s a confronting thing,” he said.