Mother Jones illustration; Democracy Now!; Getty

On March 30, 2016, in an immigration courtroom in Charlotte, North Carolina, a 2-year-old boy was doing what you might expect: He was making some noise. But Judge V. Stuart Couch—a former Marine known to have a temper—was growing frustrated. He pointed his finger at the Guatemalan child and demanded that he be quiet.

When the boy failed to obey his command, the threats began. “I have a very big dog in my office, and if you don’t be quiet, he will come out and bite you!” Couch yelled.

Couch continued, as a Spanish-language interpreter translated for the child, “Want me to go get the dog? If you don’t stop talking, I will bring the dog out. Do you want him to bite you?” Couch continued to yell at the boy throughout the hearing when he moved or made noise.

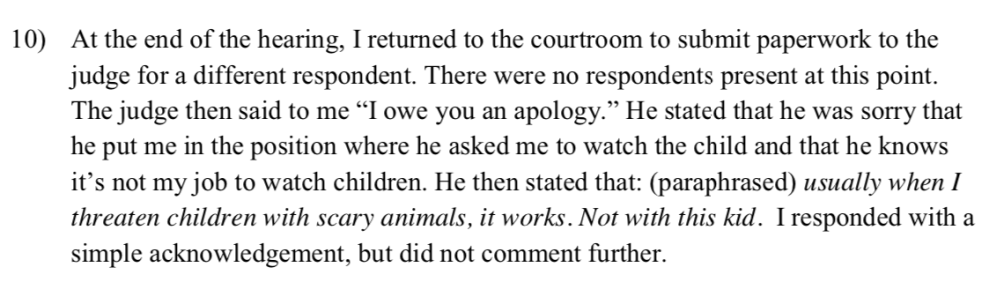

Kathryn Coiner-Collier, the only independent observer in the courtroom that day, says her mouth was on the floor as Couch made his threats. She sometimes saw Department of Homeland Security dogs sweeping the court building, and it was completely plausible to her that dogs could have been there that day. Coiner-Collier, then a coordinator for a project run by the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy to assist immigrants who couldn’t afford attorneys, says she “ferociously scribbled everything” Couch was saying. Soon after, she wrote an affidavit containing the dialogue above, and Kenneth Schorr, the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy’s executive director, submitted a complaint to the Justice Department in April 2016.

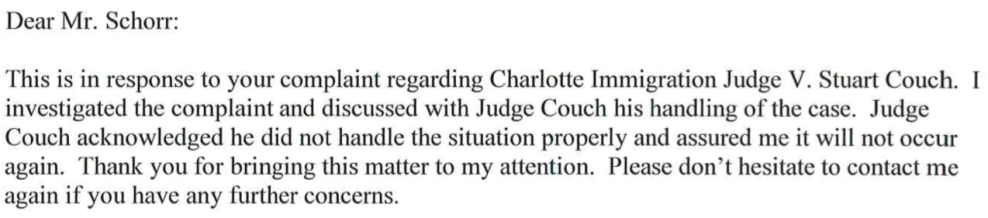

“I was outraged,” Schorr says about learning of the threats. “I’ve been practicing law for over 40 years and I have never experienced judicial conduct this bad.” Coiner-Collier says Assistant Chief Immigration Judge Deepali Nadkarni, Couch’s superior, interviewed her multiples times about the affidavit and told her that it was accurate. Schorr says Nadkarni told him that everything in the affidavit was corroborated by the internal investigation. Nadkarni wrote to Schorr in June 2016, “Judge Couch acknowledged he did not handle the situation properly and assured me it will not occur again.”

V. Stuart Couch. Credit: National Security Archive

Schorr doesn’t think that Couch should have been able to remain on the bench after his threat to call in a dog on a child. In an unexpected way, he got his wish: In August, the Trump administration promoted Couch and five other judges to the Justice Department’s Board of Immigration Appeals, which often has the final say over whether immigrants are deported. All six judges reject asylum requests at a far higher rate than the national average; Couch granted just 7.9 percent of asylum claims between 2013 and 2018, compared to the national average of about 45 percent. (Before becoming an immigration judge, Couch served as a military prosecutor and attracted widespread attention for refusing to prosecute a Guantanamo detainee because he had been tortured.)

The boy’s mother declined to comment for this story, telling her attorney that she is still afraid of Couch. The Justice Department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, which oversees the country’s immigration courts, declined to answer questions about the incident. The interpreter who translated for Couch at the hearing declined to speak on the record about the incident.

During the hearing, Coiner-Collier says Couch turned off the courtroom’s recording device as he threatened the boy. After turning it back on, he made a statement in which she believes he intentionally inflated the boy’s age to obscure the fact that he had threatened someone who was a few months shy of his third birthday, according to his passport. “I will have the record reflect that [the boy] is a 5-year-old respondent that has been very disruptive during this hearing,” Couch said, according to her recollection in the affidavit. “The court had tried to control the child behavior’s and has been unsuccessful…The court is using a strong voice and strong language with him in the absence of parental control.” (Coiner-Collier did not have access to the recording when she wrote the affidavit, but she says Nadkarni confirmed that there were multiple breaks in the recording when Couch went off the record.)

The boy was only 2, Coiner-Collier stated in the affidavit. “Anybody in their right mind looking at this child would know he is not 5, would know he is not 4,” Coiner-Collier recalls. “He was a little dude…He probably wasn’t even taller than the table.” It’s also unclear how many of Couch’s commands he was able to understand, since his first language was not Spanish but K’iche’, a Mayan language.

After Couch made the statement about his strong language, he asked Coiner-Collier to remove the boy from the courtroom. When she asked the boy to come with her, he began to cry and grabbed onto his mother. Coiner-Collier picked him up and tried to carry him out, but he got free and ran back to the courtroom. She eventually took him to a nearby room, where he screamed and cried. A few minutes later, the hearing ended, and the boy’s mother, who was also crying, rejoined her son. Others did, too. “The women and children that day—I will never forget—left court hysterically crying, almost all of them,” Coiner-Collier says. (About her own reaction, she wrote in a text message to the mother’s attorney the next year, “I have never lost my composure like I did that day…I was…red in the face sobbing along with her.)

When she went back to the courtroom to file paperwork, Couch told her, “I owe you an apology.” He said he knew it wasn’t her job to watch over children. Then he made a comment that suggested he had threatened other children. Coiner-Collier paraphrased what he said in her affidavit: “Usually when I threaten children with scary animals, it works. Not with this kid.” (Coiner-Collier and others who have appeared before Couch never witnessed him threaten another child.)

Coiner-Collier quickly told her supervisor and Schorr what had happened. Schorr asked her to draft an affidavit. Two weeks after the hearing, Schorr submitted the complaint to the Justice Department’s assistant chief immigration judge for conduct and professionalism. Schorr says Nadkarni, Couch’s superior, told him that the Justice Department would take appropriate action, but Nadkarni was not able to offer any specifics. Schorr still doesn’t know whether Couch was disciplined. (Coiner-Collier says Couch later told her that she put his job on the line by complaining.)

Nadkarni’s 2016 letter to Schorr.

During the three years she worked for the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy, Coiner-Collier says she probably spent more time in the Charlotte immigration courtrooms than anyone aside from courtroom staff. She remembers that Couch would sometimes go out of his way to explain things to the immigrants appearing before him. He could be fair and thorough, she says. But on other days, his temper took over. Noise was particularly annoying to him—a “bless you” after a sneeze could lead to a stare that she says would burn a hole in the back of your head. “He was scary as hell,” says one attorney who appeared before him. “Some days I thought he was gonna freakin’ have a heart attack on the stand because he was so worked up.”

After the 2016 hearing, Couch told Coiner-Collier that he would reassign the case of the 2-year-old and his mother, as well as other cases heard that day, to another judge. But in August 2017, the mother and son were back in court and scheduled to appear before Couch again. The mother’s attorney thought she seemed unusually nervous and asked what was up. She said Couch had yelled at her. The attorney had heard about the dog incident but didn’t know the names of the people involved, and she texted Coiner-Collier to see if her client’s son was the one who had been threatened. After learning that he was, the attorney wrote, “I cannot believe this.”

“I will never forget sitting in my office with that child after [C]ouch made the threats towards him,” Coiner-Collier replied, adding, “I was literally laying on the floor in fetal position with him and he was SCREAMING for his mother.”

The boy’s mother, the attorney texted back, “doesn’t know the word ‘trauma.’ She just keeps saying he was crying. And you and her.”

After the exchange, the attorney asked Couch to reassign the case to another judge. He agreed to do so. The new judge denied them asylum. The mother appealed, and the case is pending before the appeals board that Couch is now a member of.