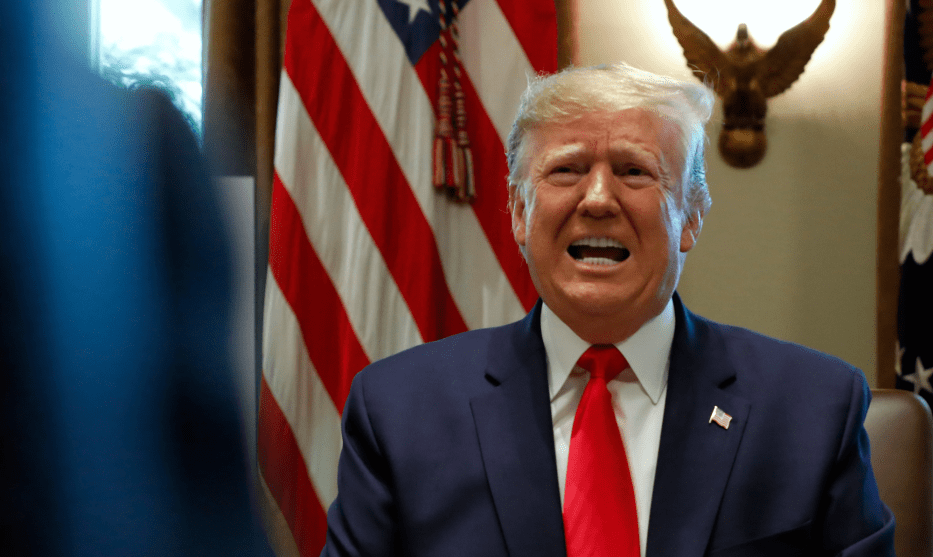

President Donald Trump speaks during a Cabinet meeting at the White House. Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

Having campaigned and governed as an avatar of embattled whiteness, Donald Trump did the inevitable on Tuesday and compared the lawful impeachment inquiry into his administration to a “lynching.” This was met with immediate ire from people who know something about lynching’s dreadful history. Kristen Clarke, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, tweeted that she was “sickened to see Trump’s gross misappropriation of this term today.”

So much of the history of lynching is the history of its misappropriation as a metaphor by powerful white people. President Richard Nixon was said to have been beset by the “lynch-mob mentality” of the Senate committee tasked with investigating Watergate. Robert Bork, a white Supreme Court nominee, and Charles Pickering, a white federal court nominee, were said to have faced a lynching in their losing confirmation fights. The judge presiding over the trial for the militantly white Timothy McVeigh decided to limit emotional testimony from survivors and victims’ relatives in the Oklahoma City bombing, lest the penalty phase of the trial become “some kind of lynching.” (The New York Times adjudged this “an essential and admirable step.”) In 1998, white Joe Biden wondered if white Bill Clinton’s impeachment was just a “partisan lynching.” In 2011, white conservative pundit Glenn Beck felt so threatened by the harassment of moviegoers in New York that he worried they would “lynch” him.

Amy Kate Bailey, a sociology professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago and co-author of Lynched: The Victims of Southern Mob Violence, sees a pattern of powerful men making the “interesting and problematic rhetorical move” of claiming to be the targets of lynchings. America’s lynching regime “was systematically inflicted as a form of violent terror,” Bailey told me. To use it as “a means of deflecting criticism and deflecting culpability for people who have access to lots of power”—and to the due process provisions of the legal system— is to contribute to what she called “a false narrative about the history of racist mob violence in the United States.”

From the mid-1800s through the early 20th century, lynching was an instrument of racial control, devastating Black men, women, and children in the South—and beyond. Close to 4,000 people were brutally beaten, drowned, burned alive, maimed, and tortured during that time period, according to E.M Beck, an emeritus professor at the University of Georgia and co-author of A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings 1882-1930. The NAACP, which called Trump’s comments a “repugnant show of ignorance,” pegs the number of lynchings between 1882 and 1968 at just over 4,700; nearly 73 percent of victims were Black. In a report titled “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” the Equal Justice Initiative found that a quarter of Black lynching victims had been accused of sexual assault, while 30 percent had been accused of murder. These allegations were often pretexts to inflict terror on Black people, and by definition, the punishments were meted out with no due process.

“We’re talking about some brutal things going on. Given that as the historical context, to have politicians come up and use that term that politicians are an insult to the victims of lynchings,” Beck told me. Jonathan Markovitz, an attorney at the ACLU in San Diego, noted that Trump is using “lynching” in a context—impeachment—in which he is being afforded all the formal protections of due process. “People were lynched not only when there were no trials but when nobody even thought that a crime was committed,” Markovitz said. “This rendering of that history divorces it from meaning and suffering.”

From the start, lynching functioned as more than a material act of violence, Markovitz argues in his book Legacies of Lynching: Racial Violence and Memory; it was a message to Black people in general. To anti-lynching advocates, lynching represented “white supremacist barbarism,” the violent expression of “an entire system of power”—a sort of metonym for racism writ large. Through the 1920s, Bailey told me, lynching was considered a “palpable reality,” especially for Black men, though Black women were no less terrorized by repressive violence, with the threat of rape acting in roughly analogous fashion to the prospect of lynching.

As the pace of lynchings declined over time, the meanings ascribed to the term began to loosen and multiply. With the expansion of the prison system, the term “legal lynching” emerged to “say that this one system of racist terrorism has been transformed into another,” Markovitz told me. Protesters notably used it to describe the series of convictions and retrials of the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers who were falsely accused in 1931 of raping two white women. Their convictions were later overturned, setting a legal precedent buttressing the right to counsel.

But the concept could also be put to reactionary use, and not just on behalf of powerful white political figures. Most famously, Clarence Thomas, on the first day of his Supreme Court confirmation hearings, said he was the victim of a “high-tech lynching for uppity blacks,” explicitly pitting the legacy of American racial atrocity against a Black woman’s claims of sexual victimization. As Markovitz noted, Thomas wanted to draw people’s attention to the historical resonances of white spectators investigating Black sexuality (though not to the fact that Black men didn’t get lynched for their supposed crimes against Black women). Years later, Ann Coulter used the same phrase, “high-tech lynching,” as she defended former Republican presidential contender and pizza magnate Herman Cain from sexual harassment allegations. That tactic, of countering allegations of sexual impropriety by invoking America’s history of racist vigilantism, was more recently employed by Bill Cosby, whose legal team called his trial a “public lynching,” and R. Kelly, who called the #MuteRKelly campaign against him an “attempted public lynching of a black man.” And in February, in a speech to Virginia senators, the state’s lieutenant governor, Justin Fairfax, brushed off calls for his resignation in the face of accusations of sexual assault by two women, essentially comparing himself to lynching victims.

Today, the idea of lynching is very much contested ground, as Trump in his oafishness has demonstrated. “Yes, African Americans were lynched, other people have people lynched throughout history,” Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) said in defending the president. “What does lynching mean? That a mob grabs you, they don’t give you a chance to defend yourself, they don’t tell you what happened to you, they just destroy you.” On the right, the meaning of lynching now occludes the actual victims of the practice in favor of powerful people who fear dispossession of one kind or another. These are people who “make claims of disempowerment that are not true in the way they were true [for people who] were publicly and brutally murdered by their own neighbors,” Bailey said.

“That’s not what’s happening to Donald Trump. That’s not what happened to Clarence Thomas. I’m not saying they aren’t feeling a feeling of being under attack. The question is how appropriate it is to try to make claims of a status and level of victimhood that’s just not true.”