Ted S. Warren / AP

In November, Seattle will elect a new city council. It is the second election in which the city’s democracy vouchers are in play, a first-of-its-kind financing program for taxpayers, which is either, depending on who you ask, the roadmap to fixing big money in politics across America or responsible for a $3 million jump in PAC spending.

In 2015, Seattle overwhelmingly passed Initiative 112 with 63 percent of the vote. The idea first surfaced in the broader public sphere in 2011, 13 months after the Citizens United decision allowed a new flood of corporate money into politics. Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig proposed a counterbalance in a New York Times op-ed: “more money.” Lessig argued that if corporations were able to classify vast sums of money as protected speech, it might be time to start asking how to match that capitalistic tide with money from the people. “[I]magine a system that gave a rebate of that first $50 [we pay in taxes] in the form of a ‘democracy voucher,'” Lessig proposed.

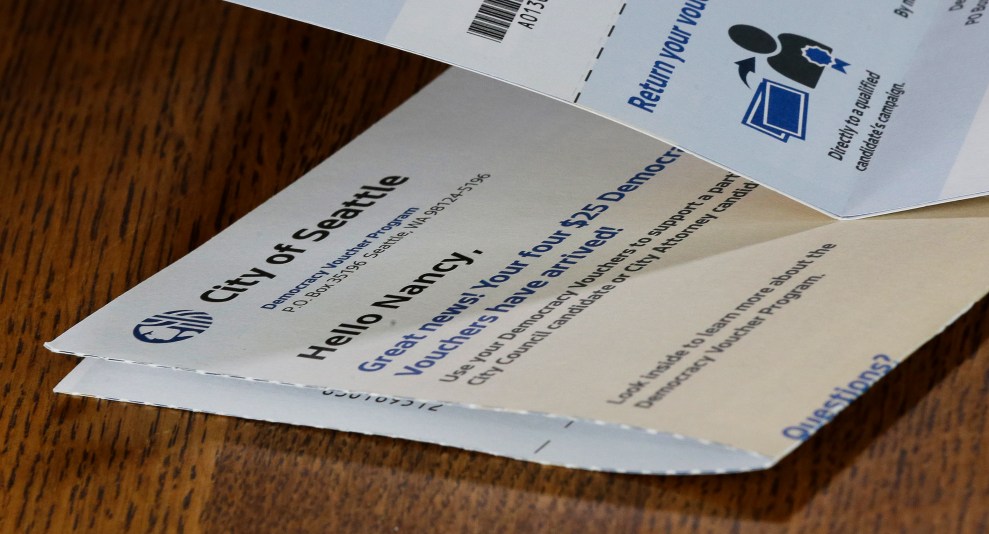

In Seattle, Alan Durning, a founder at Sightline Institute, began to imagine. He gathered a group of lawyers from the progressive policy nonprofit around a kitchen table so that they could start to “translate this theory into brass tacks,” a policy analyst at Sightline recalled. What they came to followed Lessig’s proposal closely. Each resident would receive two vouchers totaling $100 that could be given to any candidate. However, candidates must agree to a few conditions to accept the vouchers—most importantly an election specific cap on individual contributions. (If a candidate or an independent group, like a PAC, outspends the voucher user’s cap, the candidate can be released from the limit.) And the name stuck: “democracy vouchers.”

It was a hopeful moment. “There hadn’t been anything new under the public financing sun for decades—until Seattle,” said Jennifer Heerwig, a sociologist at Stony Brook University studying the program. There were signs of success in 2017, after the first election where democracy vouchers were made available; more than 20,000 people returned vouchers—only half that number made cash contributions—and voucher users were more representative of the overall electorate than cash donations. In 2015, the last off-year election for City Council that did not include a mayoral run, slightly more than 20,000 people donated to campaigns; this year, more than 40,000 have pledged support through October.

It opened doors. Emily Myers, a candidate who lost in the primary for City Council, said that as a scientist from a working-class background, “my ability to raise $15,000 in a week just wasn’t there. So the voucher program opened up some of that gatekeeping that is there for candidates.” Without it, she wouldn’t have run.

The initiative has gotten some attention as the 2020 elections are ramping up. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-New York) discussed moving the program to the national level before she dropped out of the Democratic primary. In a September debate, Andrew Yang said he wants to “give every American 100 ‘democracy dollars’ that you can only give to candidates and causes that you like.” There was a legitimate critique circulating afterward that the plan falls into Yang’s penchant for squeezing down tough policy problems into one-size-fits-all technocratic solutions with weird names, but some Seattlites had first-hand critiques of the program itself.

“Hoo boy,” wrote Danny Westneat, a columnist at the Seattle Times. “Message to rest of nation: Copying what we did here will NOT wash special interest money out of your politics.”

Westneat is referring to the somewhat unusual circumstances of the upcoming city council race. In January 2014, Kshama Sawant became the first socialist City Council member in modern Seattle history. Sawant, alongside other progressive councilmembers, has driven a hard agenda on progressives issue that has clashed with business interests. It was her shepherding of the “head tax”—a per-employee charge on large corporations making more than $20 million per year that was passed and then quickly repealed by the council—that divided the tech-friendly, ultra-liberal city. “We have a slate of seven races where there is a business side and there is a left-progressive side (and again, these are shades of left),” explained Bob Mohan, a lawyer in Seattle. “I think that could be driving a lot of the expenditures.”

People for Seattle, a PAC close to the Chamber of Commerce that has nearly $400,000 in contributions from tech executives like Tom Alberg (Amazon), John Stanton (“wireless pioneer“), Christopher Larsen (Microsoft) has circulated flyers that call Sawant an “extremist.” Amazon recently announced it invested another $1 million in Civic Alliance for a Sound Economy, another anti-Sawant PAC, bringing their total spending this cycle to nearly $1.5 million. The boost raised the amount given to independent expenditure committees over $4 million, according to the Seattle Times. Critics say that since the vouchers put more money into elections and limited individual contributions to candidates, the wealthy have gone all-in on PACs—leading to soaring contributions in individual expenditures. Mohan, who opposed the initiative, told Mother Jones that his concern was that the protections established in Citizens United means that “any well-intention effort to plug [spending] is just going to result in people going around it.”

“The election cycle’s been kind of bonkers,” admits Vy Nguyen, a staffer for Councilmember M. Lorena González, who recently proposed a bill that would cap contributions by political committees.

The democracy voucher program never promised to totally solve corporate contributions, but it did offer an opportunity to widen the candidate and donator pool. Liz Dupee, who worked as a housing advocate before moving to Democracy Hub to help advocate for the vouchers, was convinced in part to join the effort because it helped her former boss, Jon Grant, run for city council on a housing platform. (Grant, somewhat famously, went to a homeless encampment to ask for donations from vouchers.)

Austin, Texas is considering a similar program, as is Albuquerque, New Mexico. If the democracy vouchers philosophy were to expand, Heerwig said that Seattle’s ability to release candidates from the limitations on independent donations would be important.

Either way, Cindy Black, of Fix Democracy First, a fair elections group that helped champion the legislation, said democracy vouchers are better thought of as one part of a larger fight. “One of the things that we advocate is for a long-term solution is a constitutional amendment that would overturn [Citizens United],” she said. “But we know the reality is that we’re a long way off.”