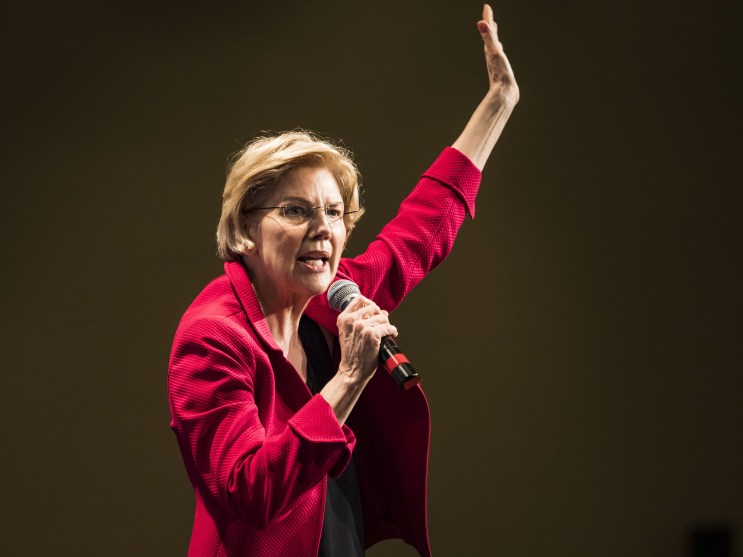

Elizabeth Warren addresses a crowd at Clinton College, an HBCU in Rock Hill, S.C., on September 28, 2019.Meg Kinnard/AP

Elizabeth Warren came to the South Carolina Lowcountry on Saturday and played all the standards. At a town hall in Goose Creek, about 20 miles north of Charleston, she talked about corporate greed and government decisions that put the wealthy few ahead of the working many, before rounding into her proposals for voting reforms that would strengthen democracy. This was an important part of her message in South Carolina, the crescendo where she could address herself directly to the procedural impediments facing the state’s many Black voters. The crowd was with her, too, cheering wildly when she promised to end the gerrymandering practices that have historically disempowered racial minorities and to “end racist voter suppression.”

The curious part was that, by my count, the audience of 750 or so people was at least 80 percent white. Several attendees I’d spoken with had driven up from Charleston, an ever-gentrifying, ever-whitening coastal city full of transplants who’ve fled colder climates for the Sun Belt. For this predominantly white crowd, some of the day’s biggest applause lines were about ending structural racism against Black people.

In its swing through South Carolina, host of the fourth nominating contest in the Democratic presidential primary, Warren’s campaign has gotten a glimpse of the central dynamic in the so-called “Great Awokening,” the name given to our current era of expanding racial consciousness among white liberals. Pitching herself to Black voters who are essential to winning the state’s primary, Warren finds herself firing up white liberals.

I asked Warren after the Goose Creek town hall why she thought a majority-white audience responded so enthusiastically to the explicitly antiracist parts of her message. “I think people understand that our democracy is broken,” she told me, reiterating her points about why rich people don’t deserve a bigger share of it. She added, “One of the most fun parts about being out and doing this town halls”—Goose Creek is her 160th of the cycle—”is how engaged people are over rebuilding our democracy.”

It’s hard to say whether the Warren campaign might have expected a different mix of folks to show up to see her on Saturday. Goose Creek High School serves a majority-minority student body that’s 40 percent Black, 30 percent white, and 15 percent Latino; the town and surrounding areas hew closer to 70 percent white, though nearby North Charleston—about halfway between Goose Creek and downtown Charleston—is nearly 50 percent Black.

But the town hall was the last stop on Warren’s three-day swing through the Carolinas focused on wooing nonwhite voters and highlighting her racial equality message. It included an appearance at an environmental justice forum aimed at highlighting how communities of color disproportionately suffer the effects of environmental inaction, as well as an education forum in Summerton, South Carolina, a majority-Black town in the state’s “Corridor of Shame,” so called for its history of educational inequality, poor school funding, and low educational achievement. On Thursday, Warren appeared in Raleigh, North Carolina, alongside Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), who had endorsed Warren’s candidacy earlier that day.

Warren’s mission set her up for some obvious questions. At the environmental justice forum, moderator Amy Goodman pressed Warren on whether Iowa and New Hampshire—“two of the whitest states”—should be the first states to host presidential primaries. Warren huffed a little and dodged the question, noting she’s “just a player in the game on this one.”

Elizabeth Warren berates Amy Goodman for asking her a reasonable question she refuses to answer, then ends the interview by replying to Goodman's "thank you" with a scoffed "yeah."

Her disdain for the left couldn't be more blatant.pic.twitter.com/CeALdRy4e3

— DSA Otherkin Caucus ❼ (@QueenInYeIIow) November 9, 2019

Following her Goose Creek town hall, a reporter pointed out the majority-white audience and asked what the campaign’s strategy is to diversify its crowds. Warren replied with her own question, asking the reporter if she’d seen the majority-Black audience who gathered in a high school library to see her speak with educators in Summerton.

“It’s keep showing up and keep reaching out,” Warren said of her approach. “I want to introduce myself to every single voter in South Carolina. And that’s true, regardless of what their race is, what their gender is, what their party affiliation is—2020 is our chance, our chance to turn around a country that’s working great for those at the top and not so much for” everyone else.

At its core, Warren’s campaign poses the question of whom government works for—the answer, of course, being the wealthy and well-connected. But there’s a line she almost always chases that point with. “Why are working families finding the path so much harder than generations ago?” she’ll say, as she said in Summerton that morning and again that afternoon in Goose Creek. “And why, for people of color, is it even rockier, even steeper?”

Warren is acknowledging the entwinement of racial and class inequalities in a way that seemed to energize the white supporters I spoke with at her events in South Carolina. Christine Jasonis, a white retiree and South Carolina transplant originally from Connecticut, says Warren’s education and Medicare for All plans appeal to her, but she feels “very strongly” about Warren’s antiracism. “If I was a mother of a young Black man today, I would be terrified,” she says. “We fought too hard for this.”

Alec Neller, a white twentysomething who recently graduated from college, told me systemic racism was his top voting issue—and a reason he’s drawn to Warren. “Everyone should have the opportunity to succeed and do what they dream. It makes for a stronger United States and a stronger world,” he said. “I think Trump put [racial inequality] on the table by attacking certain minority groups and calling certain countries ‘shitholes.’”

Trump’s oafishness, while emboldening racists across America, has also had the effect of making racism more obvious to the sort of white liberals who might not have been paying close attention. “You have people saying, ‘Oh, I thought racism was supposed to be over, but clearly, it’s not,’” said Jillian Clayton, a white woman who’s backing Warren.

Clayton, who attended the College of Charleston in the mid-2000s and has lived in the area since, sees something similar at work in her own city. White residents witnessing Charleston’s transformation have become highly attuned to gentrification’s effects, she said, even if they’re also reaping some of its benefits. “We see it happening every day,” she said. “People are getting pushed farther and farther away from the city.”

Back in March, Vox’s Matt Yglesias wrote about the Great Awokening through the lens of researchers and pollsters who have observed a sharp increase in concern among white Democrats about racial inequality and discrimination over the past five years. Yglesias pointed to polling from the Pew Research Center that, back in 2014, found that most Americans didn’t think there was any work left to do to address Black-white inequality. Now, more than 80 percent of self-identifying Democrats say the country needs to make changes to give Black Americans the same rights as whites. Until recently, according to the left-leaning think tank Data for Progress, most white Democrats ascribed racial inequality to a lack of individual initiative. Today, as Yglesias writes, white liberals are now “less likely than African Americans to say that black people should be able to get ahead without any special help.”

The Great Awokening was Yglesias’ coinage, a reference to the religious revival among white Northerners in the years before the Civil War that lent a moral fervor to abolitionist movements. And he predicted similar results for this current moment. “The fundamental reality is that the Awokening has inspired a large minority of white Americans to begin regarding systemic racial discrimination as a fundamental problem in American life—opening up the prospects of sweeping policy change when the newly invigorated anti-racist coalition does come to power,” Yglesias wrote.

Warren has been steadily rising in the polls of South Carolina, where more than 50 percent of the primary electorate is Black. The Post and Courier’s first poll back in May put Warren at a dismal 8 percent behind Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, and Joe Biden, who received 46 percent of support. The latest Post and Courier survey, conducted in mid-October, found Warren in second place at 19 percent, only 11 points behind Biden. Though pollster Pat Reilly did not directly explain Warren’s rise, he told the Post and Courier that Biden’s drop came “principally from African-American women who are moving to other candidates,” though “none of the top candidates are seeing a decisive jump as a result.”

The rate of conversion suggests that Black women might be moving toward Warren. At the event in Summerton I watched the candidate use her own story to establish a connection. The education forum had been an intimate gathering of a few dozen attendees—among them local elected officials, business owners, and faith leaders, all of whom told me it was too early for them to throw their support behind any of the Democratic candidates. As Warren recounted her familiar anecdote about how, as a preschool teacher in the 1970s, her contract wasn’t renewed when she became visibly pregnant, a number of Black women in the audience nodded knowingly. A few told me afterward that their friends had had similar experiences during that era.

But there was still work to be done, as the demographics of the Goose Creek event suggest. Just before Warren began speaking there, I met Amelia Duvall, who was standing by herself near the back of the gymnasium. Duvall, a Black woman and business owner from nearby Ladson, had attended the town hall alone. She’s supporting Warren, but when I asked her what she thought of attendance, she shook her head. “She’s gotta get more people in here who look like me,” she said.