When I walked into the Obria clinic in Whittier, California, one evening in July, a woman in a modest floral-print dress organizing bundles of diapers in a back room greeted me hopefully. She thought I’d come for a class. Instead, I asked if I had come to the right place for birth control. Furrowing her brow, she walked around a couch and through a cozy waiting room full of baby toys to the front desk. “What sort of services were you looking for?” she inquired. I asked if they dispensed the morning-after pill, the emergency contraception often called “Plan B.” She told me curtly, “We don’t provide that or refer for any birth control here.”

I wasn’t surprised. For most of its existence, this clinic has been known as the Whittier Pregnancy Care Clinic, a religious ministry that offers free pregnancy tests and ultrasounds in the hopes of dissuading women facing an unplanned pregnancy from having an abortion. The clinic provides lots of things: free diapers and baby supplies, and post-abortion Bible-based counseling. What the clinic has never provided is birth control.

When the Whittier clinic was strictly saving babies for the Lord, its refusal to dispense even a single condom was a private religious matter in the eyes of its funders. But today, the clinic is part of Obria, a Southern California–based chain of Christian pregnancy centers that in March won a $5.1 million Title X grant to provide contraception and family planning services to low-income women over three years. Created in 1970, Title X is the only federal program solely devoted to providing family planning services across the country. Congress created the program to fulfill President Richard Nixon’s promise that “no American woman should be denied access to family planning assistance because of her economic condition.” It serves 4 million low-income people nationwide annually on a budget of about $286 million and is estimated to prevent more than 800,000 unintended pregnancies every year.

Historically, federal regulations required that any organization receiving Title X funding “provide a broad range of acceptable and effective medically approved family planning methods.” But as I discovered during my visit to Whittier and other Obria clinics last summer, the organization’s clinics refuse to provide contraception. Nor do they refer patients to other providers for birth control.

Obria’s founder is opposed to all FDA-approved forms of birth control and has privately reassured anti-abortion donors that Obria will never dispense contraception, even as she has aggressively sought federal funding that requires exactly those services. “We’re an abstinence-only organization. It always works,” Kathleen Eaton Bravo told the Catholic World Report in 2011. “And for those single women who have had sex before marriage, we encourage them to embrace a second virginity.”

Mara Gandal-Powers, director of birth control access at the nonprofit National Women’s Law Center, does not think Bravo’s stance “is in line with the intent of the Title X family planning program, but obviously they see it differently.”

Should the Trump administration survive another four years, Obria may represent the future of the Title X program. In 2019, the Department of Health and Human Services instituted a gag rule that banned clinics getting Title X money from providing patients with referrals for abortions. (Federal law prohibits the program from funding abortions.) Seven state governments and Planned Parenthood, which served 40 percent of Title X patients, decided to drop out of the program rather than comply.

But even before Planned Parenthood was squeezed out, the White House had been pushing to redirect Title X and other federal funds to anti-abortion organizations like the Whittier clinic, which juggles its mandates of health care and family planning with pushing abstinence-only sex education, dissuading women from having abortions, and introducing them “to the love of Christ,” as its website says. In July, HHS awarded Obria nearly $500,000 from its teen pregnancy prevention program to provide “sexual risk avoidance” classes.

The Obria grant suggests that the Trump administration’s assault on Title X is not just about reducing abortion access. It’s part of the broader, if largely futile, culture war still waged by evangelical and other Christian conservatives heaven-bent on making America chaste again. Abstinence-only activists now control key posts at HHS and are driving policies that force their views about contraception onto the vast majority of Americans, who don’t agree with them. While Americans’ opinions on abortion are mixed, only 4 percent think contraception is immoral, and 99 percent of women who have had sex have used it. Which raises a big question: Now that Obria has won millions in taxpayer dollars to provide anti-abortion family planning services, will anyone use what they are offering?

A screenshot of the Obria website

Obria is the brainchild of Kathleen Eaton Bravo, a devout Catholic who set out to build a pro-life alternative to Planned Parenthood. “I wanted to create a comprehensive medical clinic model that could compete nose-to-nose with the large abortion providers,” she wrote on the Obria Group website. Bravo may seek to emulate Planned Parenthood’s organizational model, but she holds a dim view of it otherwise. In a 2015 interview with Catholic World Report, she claimed Planned Parenthood promoted a “‘hook-up,’ contraceptive mentality among our young people. They teach children as young as 12 that they can have sex without consequences.” She went on: “Today, Planned Parenthood promotes oral sex, anal sex, and S&M sex.”

Bravo did not respond to repeated requests for an interview. But she has said elsewhere that her involvement with the anti-abortion movement began after having an abortion in California in 1980 amid the collapse of a first marriage. Afterward, she remarried, moved to Oklahoma, rediscovered her Catholic faith, and started volunteering at a pregnancy center that tried to convince women to carry unplanned pregnancies to term. Bravo has described driving to Kansas to pray in front of the clinic of Dr. George Tiller, who would be murdered in 2009 by an anti-abortion extremist.

In Bravo’s public statements, there are echoes of the “great replacement” theory of abortion that’s become popular among white supremacists. Abortion, she told Catholic World Report, “threatens our culture’s survival. Take the example of Europe. When its nations accepted contraception and abortion, they stopped replacing their population. Christianity began to die out. And, with Europeans having no children, immigrant Muslims came in to replace them, and now the culture of Europe is changing. The US faces a similar future.”

After moving back to Southern California in the mid-1980s, Bravo took over a crisis pregnancy center in Mission Viejo called Birthright, whose name she later changed to Birth Choice. Crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs) have been an integral part of the anti-abortion movement for more than 50 years. The founder of the first known American CPC, Robert Pearson, pioneered the deceptive practices that would come to characterize their services to this day. He published a training manual that coached activists to set up CPCs to look like abortion clinics and use misleading ads to trick pregnant women into thinking they could get an abortion there. CPCs have a long, well-documented record of using high-pressure tactics on unsuspecting women and peddling misinformation like the myths that abortion causes breast cancer, infertility, and suicide.

Over the past three decades, pro-choice organizations, Democratic members of Congress, and state attorneys general have tried to expose and rein in some of the CPCs’ worst abuses. In 2015, California enacted the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act, which required unlicensed CPCs to prominently disclose that they don’t provide medical care (including abortions), and licensed ones to inform clients that the state offers free or low-cost family planning and abortion services. The CPC industry sued, and the Supreme Court struck down the law in 2018.

Obria’s clinics don’t appear to have ever been sanctioned by any government agencies for deceptive practices, but its Whittier clinic was one of many Los Angeles CPCs that a local public radio station found openly flouting the FACT Act before the act was overturned. And Obria’s RealOptions, a Northern California CPC chain that’s a recipient of its Title X grant, was caught using mobile surveillance technology to target ads at women inside family planning clinics.

In 2015, the company hired a Massachusetts-based ad firm to set up virtual “fences” around family planning clinics to target “abortion-minded women,” according to the Massachusetts attorney general. When women entered the clinics, their smartphones would trip the fence, triggering a barrage of online RealOptions ads that said things like “Pregnant? It’s your choice. You have time…Be informed.” The ads, which steered women to the pregnancy center’s site, would continue to appear on their devices for a month after their clinic visit. The Massachusetts attorney general secured a settlement with the ad firm to end the practice in 2017 after alleging that it violated consumer protection laws.

Bravo’s vision for an anti-abortion rival to Planned Parenthood is deeply rooted in the crisis pregnancy center world. Bravo has said she wants to transform CPCs from “Pampers and a prayer” ministries into a network of “life-affirming” clinics that provide many of the services Planned Parenthood does—STI testing, ultrasounds, and cervical cancer screenings, but without the birth control, abortion, or abortion referrals. “I would close my doors before I do that,” she told the Heritage Foundation’s Daily Signal in 2015.

By the middle of 2006, Bravo had expanded Birth Choice to include four CPCs. She got the centers licensed and accredited as community clinics and installed ultrasound machines to increase their “conversion rate” by convincing abortion-minded women to stay pregnant. Grants from the evangelical Christian advocacy group Focus on the Family and the Catholic Knights of Columbus paid for the machines. In 2014, she rebranded the nonprofit chain as Obria (a vaguely medicalized name made up by a marketing firm, ostensibly based on the Spanish word obra, meaning “work”) and announced an aggressive expansion plan. Bravo became the CEO of a new nonprofit umbrella organization called the Obria Group and essentially turned the operation into a franchise.

The Obria Group doesn’t provide any medical services or even start new clinics. Rather, it’s a marketing arm that recruits existing CPCs to join the Obria network. Affiliated clinics pay a licensing fee to use the Obria name, but they remain separate legal entities with their own nonprofit status. (Bravo’s Birth Choice clinics are now a separate nonprofit called Obria Medical Clinics of Southern California, and she is no longer employed there or on its board.)

Bravo is politically well connected. On the Obria website, she brags that she “has built a network of high-powered supporters over the decades to include former U.S. presidents, Washington lawmakers, senators, prominent mega-churches, spiritual leaders and thousands of behind-the-scene players who move mountains to get things done.” Catholic World Report ran a prominent photo of her with President George W. Bush in 2010, when a Catholic business group presented them each with a Cardinal John J. O’Connor pro-life award. Obria’s advisory board was a who’s who of the pro-life movement, including Jim Daly, president of Focus on the Family; Kristan Hawkins, a former official in Bush’s Department of Health and Human Services who worked on Trump’s pro-life advisory council during the 2016 campaign; and David Daleiden, CEO of the Center for Medical Progress, who was criminally charged in San Francisco for making undercover videos purporting to show Planned Parenthood selling tissue from aborted fetuses.

The Catholic Church and wealthy Catholic donors have provided much of Obria’s funding, including a $2.5 million grant from the US Conference of Catholic Bishops for Obria’s expansion plans. But Bravo has also secured public funding. In 2005, Birth Choice nabbed a $148,800 congressional earmark to fund three pregnancy centers. Between 2009 and 2016, the Orange County Board of Supervisors gave the Obria Medical Clinics of Southern California more than $700,000 for abstinence-only sex-ed programming, money that had previously gone to Planned Parenthood. Obria has even scored help from Google, which in 2015 gave Obria $120,000 worth of free ads through its nonprofit grant program.

This funding supports limited clinical offerings such as pregnancy testing, ultrasounds, and some STI testing and cervical cancer screening. A few clinics offer “abortion pill reversal,” the practice of giving women large doses of progesterone to try to halt a medically induced abortion in progress. (The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says the treatment is not supported by science.)

Obria’s medical director, Peter Anzaldo, is an Orange County OB-GYN and cosmetic surgeon who offers “mommy makeovers” in his private practice, using lasers to “rejuvenate” aging vaginas—a controversial procedure the FDA has warned against as unapproved and potentially unsafe. While he provides many forms of contraception, including sterilization, at his office, Obria’s contraception offerings consist of educational lectures about its various dangers, with a focus on abstinence until marriage. Despite providing STI testing and treatment, Obria won’t dispense condoms, even now that it’s received Title X money that’s supposed to go toward combating STIs.

However, Obria will help women learn the Catholic Church-approved “natural family planning,” a more complicated version of the rhythm method. Natural family planning requires women to regularly monitor their vaginal mucus and chart their temperature to avoid sex during ovulation. Obria claims on its website that the natural family planning success rate ranges from 75 to nearly 90 percent. The CDC cites a study showing that 24 percent of women became unintentionally pregnant within a year of using natural family planning, making this method one of the least effective forms of birth control.

For years, in speeches and fundraising pitches, Bravo has tried to sell Obria as a health care operation, not just a ministry, and its clinics seem to take great pains to downplay any outward evidence of its religious mission. The California clinics resemble doctors’ offices, and that’s by design. Obria’s affiliate application asks CPCs whether their staff is “taught not to force religious beliefs or practices on patients,” and it checks to make sure they don’t have any crosses or bloody fetus photos displayed in their facilities. In a nod to the bad actors of the crisis pregnancy world, it also asks whether the applicant has ever been accused of false advertising. But Obria’s implicit religious mission still seems to seep into its medical practice.

In 2018, after taking a home pregnancy test, a 27-year-old woman who asked to be identified as Huong visited the Obria affiliate in San Jose, California, which is part of the RealOptions CPC network. She’d recently been diagnosed with endometriosis with a procedure she hadn’t known would temporarily increase her fertility. She was shocked to learn she was pregnant. “It was a very difficult time in my life,” Huong recalled. “I was confused, scared. I just felt like I was 14 again.” She was in an on-and-off relationship and strapped for cash. She looked online and found Obria.

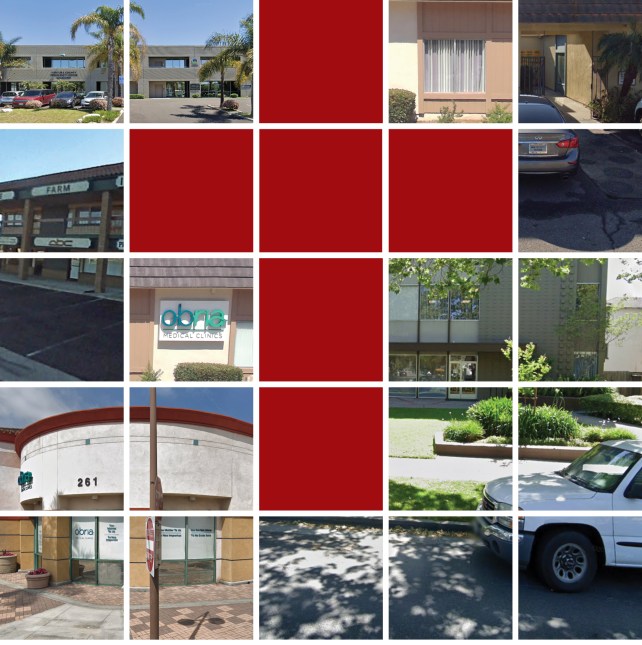

Most crisis pregnancy centers appear to be conventional medical offices and are usually located near abortion facilities.

Mother Jones illustration; Google

At first, Huong thought Obria was an ordinary medical clinic. But when she told a clinic worker she was considering an abortion, the woman “visibly looked appalled,” Huong said. “She said, ‘I see here that you’re 27. Why don’t you just get married?’” When Huong said she didn’t believe in marriage, she recalled that the woman asked, “Why don’t you just give it up for adoption?”

“I just felt like the scum of the earth,” Huong said. “I walked into this clinic thinking they were going to help me, and they were telling me to keep the baby and that I’m a piece of trash for even considering abortion.”

During an ultrasound, the nurse told Huong that she had friends with endometriosis who had become infertile—and that this might be her last chance to conceive, an assessment she later learned was false. The nurse also said that if Huong’s boyfriend was unsure about having a baby, the clinic would do the ultrasound again for free so he could see the fetus—a practice that CPCs sometimes use to convince women to continue an unplanned pregnancy. Huong ended up having an abortion at Planned Parenthood. She said her experience at Obria was far more traumatic than the abortion itself. “I remember feeling the worst I’ve ever felt in my life,” she said. “It just messed me up.”

The Obria medical clinic in Long Beach sits in a busy, low-rent strip mall, nestled between a Hong Kong Express and a Rent-a-Center. The clinic’s tiny waiting room has space for three or four people, but that wasn’t a problem when I visited one morning in July. No one was waiting when I asked the woman at the front desk for the morning-after pill. “No, we don’t do the morning-after pill or any sort of birth control,” she said. When I asked if she knew where I might find it, she said no. The morning-after pill is available at most pharmacies without a prescription. And like most crisis pregnancy centers, this one has set up shop near an abortion clinic—two of them, in fact. It’s a three-minute walk from one of the state’s oldest abortion and family planning clinics and a six-minute walk from a Planned Parenthood.

I waited outside the clinic for an hour or so, hoping to find some patients to interview. But none came in. Out of curiosity, I crossed the Metro tracks to FPA Women’s Health, which offers a full range of contraception. It isn’t a Title X clinic, but it takes Medi-Cal, the state insurance for low-income Californians that Obria also accepts. I counted 16 people in its expansive waiting room. A woman in line was complaining because appointments were running behind schedule. I also paid a visit to the Planned Parenthood nearby. Its waiting room was full.

I wasn’t just catching Obria on an off day. As a licensed community clinic, Obria is required to provide the state with annual data about services and clients. In 2018, its Long Beach clinic reported seeing 628 patients, fewer than two per day. The clinic didn’t report conducting a single Pap smear or HIV test, and brought in just a little more than $10,000 in net revenue from patients. By contrast, in 2018, Planned Parenthood’s Long Beach clinic reported seeing more than 9,400 patients. It performed 562 Pap smears. At both clinics, most patients whose income was recorded were on Medi-Cal, and almost half were poor, paying out of pocket for services on a sliding scale. The state insurance plan accounted for a big chunk of Planned Parenthood’s more than $3 million in net revenue from patients. (As a private practice, FPA Women’s Health isn’t required to report its client data to the state.) In fact, Planned Parenthood’s Long Beach clinic saw twice as many patients than all of Obria’s licensed California clinics combined, which reported serving fewer than 4,500 patients in 2018. Not one of those clinics reported conducting a single Pap smear or HIV test.

Women with choices perhaps aren’t all that interested in what Obria is selling. That’s no surprise; according to the federal Office of Population Affairs, just 1 in 200 patients in the Title X program use natural family planning as their primary form of contraception. “Even if Obria was offering the full range of contraceptive services, which from what I’m able to tell they are not, they don’t have experience doing family planning and serving these populations,” said Gandal-Powers of the National Women’s Law Center. “There’s something to be said for serving the people who the grants are supposed to help.”

Even if the Trump administration showered Obria with more federal funds, it’s not clear that many more women would use its clinics. In 2013, Texas kicked Planned Parenthood out of its state family planning program, and in 2016, to fill the void, the state funneled millions of dollars to an anti-abortion organization called the Heidi Group. The Heidi Group had promised it would serve 70,000 patients a year through a network of CPCs and other providers. But in 2017, the organization served just over 3,300 people, according to the Texas Observer. The Heidi Group’s performance was so bad that in 2018 the state pulled the plug on its contract and began investigating its spending. The group then partnered with Obria to apply unsuccessfully for a Title X grant in Texas. This month, a state inspector general found that the Heidi Group should reimburse the state $1.5 million in misspent contract funds it received for inflated payments and prohibited expenses for things like food, clothing and gift cards.

Despite the lack of demand for her organization’s services, Kathleen Bravo has repeatedly claimed that the network is making massive expansion plans. In 2014, she announced a new infusion of funds from the US Conference of Catholic Bishops, and said that Obria would grow to 200 clinics by 2020. Obria did not respond to a request for a full list of its locations, but at a September 2019 anti-abortion conference, Bravo put the number of Obria clinics at just 48. Using California state data, Obria’s website, and documents the group provided to HHS as part of Obria’s three Title X grant applications, Mother Jones could identify even fewer—only 18 brick-and-mortar clinics, plus four mobile clinics.

In 2017, Obria hired Abby Johnson, a former Planned Parenthood clinic director turned pro-life activist, to manage its expansion. Distressed by what she saw on the inside, she ended up quitting Obria after about a year. She has since become one of the network’s most outspoken anti-abortion critics in part because she believes Obria is misleading the anti-choice movement about its operations, including how many clinics it actually has. For instance, she said, Obria would tell donors it had five or six clinics in Oregon, when in fact it had one brick-and-mortar clinic in the state, plus a mobile van that would park in a different location every day.

Bravo had convinced the US Conference of Catholic Bishops that “they were going to be saving all these babies from abortion, and here they were four years later and none of that [expansion] happened,” Johnson said. “In fact, the clinics in California were bleeding money.” One of the reasons is that Obria was thousands of dollars behind in its Medi-Cal billing. “They didn’t know what they were doing,” she said. “They didn’t know how to bill.”

State data and IRS forms support her account. One of Obria’s California clinics closed in 2017 after serving only 45 patients that year. Obria’s tax forms show that its Southern California nonprofit was running a deficit and that grants and donations had fallen sharply, from $2.8 million in 2016 to $1.7 million in 2017. While the Southern California clinics were losing money, contributions to the Obria Group jumped from almost zero in 2014 and 2015 to more than $800,000 in the fiscal year ending in September 2017. The Obria Group doesn’t provide any health care services or run any clinics, but it does pay Bravo $192,000 a year in salary and benefits, almost a quarter of the $800,000 it raised in 2017.

When she worked at Obria, Johnson said she had argued against applying for Title X funding because she believed it would require the organization to provide referrals for contraception, which would conflict with its values and upset its anti-abortion benefactors. Officials at HHS “made it very clear to me that yes, Title X requires a contraceptive referral,” she said. “There is absolutely no way to get around that.” But Obria went after the federal funding anyway.

“If we get funded through Title X, we can advance our technology, we can advance our reach, we can serve more patients, we can expand our services,” Bravo said in a Facebook video posted by Students for Life. Yet Obria’s grant proposal indicates that if it received all the money it was asking for—about $6 million over three years—the Obria affiliate clinics in California would still serve only 5,500 patients, about 1,000 more than in 2018. The Title X grant “was absolutely a cash grab for them,” Johnson said, “because they are sinking.”

Anti-abortion activist Abby Johnson joined Obria in 2017, but she quit after about a year. She has since become one of the network’s most outspoken anti-abortion critics.

Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto/Getty

Over the past few years, the Trump administration has waged war on Title X as part of its larger mission to defund Planned Parenthood. In 2017, HHS forced all organizations receiving multiyear Title X grants to reapply for the funds on short notice. In February 2018, under the leadership of Valerie Huber, an abstinence-only sex-ed activist who was then the acting assistant secretary for population affairs, HHS rewrote the grants’ rules. The new funding announcement contained no mention of contraception and gave preference to poorly funded faith-based organizations that focused on natural family planning and abstinence.

Historically, an independent review committee evaluated Title X grant applications, and regional HHS career administrators would make the final awards. The process, created in the 1980s to keep politics out of grant-making, has been undone by the Trump administration. In 2018, it announced that the deputy assistant secretary for population affairs, a political appointee, would make final Title X decisions. Since May 2018, that role has been filled by Diane Foley, a pediatrician who through 2016 ran a Colorado Christian anti-abortion group with ties to Focus on the Family and who has promoted abstinence-only sex-ed programs. (She has said that teaching kids to use condoms by, say, putting them on bananas could be “sexually harassing.”)

Even with the playing field tilted in Obria’s favor, Politico reported that HHS rejected the group’s 2018 funding application because it refused to offer contraception. So Obria tried a different tack: It reapplied, this time focusing solely on California and promising to provide a broad range of birth control through a partnership with two federally qualified health centers that already offer contraception and sterilization services. Those two subcontractors would serve more than 40 percent of the 12,000 clients Obria promised to handle through the Title X grant. The application angered many in the anti-abortion movement. Other anti-choice organizations that had initially sought Title X funds from the Trump administration eventually withdrew from the process after HHS told them they’d have to provide contraception or refer clients to partner groups that did. These organizations didn’t see how Obria could do this without violating their anti-abortion values.

If Obria “did find a way to avoid providing or referring for contraception, it would be impressive, and we would applaud them,” Christine Accurso, executive director of a consortium of anti-abortion health care centers, told the National Catholic Register not long after HHS announced Obria’s Title X award. “However, we have confirmed multiple times from HHS leadership that a sub-grantee is required to refer for contraceptives if they do not provide them.”

Bravo had privately reassured donors in January 2019 that Obria would never dispense contraception or refer for it. “Obria’s clinic model is committed to never provide hormonal contraception nor abortions! Obria promotes abstinence-based sexual risk avoidance education—the most effective public health model for promoting healthy behaviors,” Bravo wrote in an email obtained by the Campaign for Accountability, a liberal watchdog group that has sued HHS to get public records about the Obria grant.

In March, HHS awarded $1.7 million for Obria’s California proposal, with the potential for a total of more than $5 million over the next three years. “Title X was created to help low-income women control their reproductive futures by providing them access to birth control,” said Alice Huling, counsel for the Campaign for Accountability. “Yet HHS gave these funds to a group that is fundamentally opposed to birth control. It just doesn’t make sense.”

Many things about the Obria grant make no sense, including where the money is going. In the October 2019 directory of Title X service sites published by HHS, Obria is listed as a grantee, with seven California services sites plus a mobile van. There is no mention of the federally qualified health centers that were supposed to provide the forms of contraception required under the grant. HHS declined to provide any information about the services Obria offered and wouldn’t say whether the group is required to provide birth control referrals at its clinics. Obria did not respond to multiple requests for a full list of where its Title X family planning services will be provided, or by whom.

Obria’s California proposal did indicate that a community health organization called Culture of Life Family Services would provide Title X services at two sites to at least 750 patients a year. The organization’s medical director is George Delgado, a family medicine doctor known for pioneering the bogus “abortion pill reversal.” Culture of Life doesn’t provide contraception and it also won’t make referrals for it. Johnson, the former Obria expansion director, said Obria included Culture of Life in its grant application without Delgado’s permission. She said Delgado only learned about it after Obria submitted the application, and that he had to inform HHS that his pro-life clinic could not participate in Title X. Neither Obria nor Delgado responded to questions about the grant. Obria’s grant application doesn’t contain a letter of commitment from Culture of Life, as it does for its other partners, and Obria’s PR firm told the Guardian in July 2019 that Delgado’s clinic was not on its final list of subgrantees.

At least one other clinic that was part of Obria’s California grant application doesn’t appear in the October 2019 Title X provider directory. Horizon Pregnancy Clinic, a CPC in Huntington Beach, was supposed to handle 500 of the 12,000 clients Obria promised to serve annually. Debra Tous, Horizon’s executive director, said in an email in August that she did not know the details of Obria’s Title X grant, which started on April 1. “We are still in beginning stages of discussing what is involved,” she said before referring further questions to Obria.

The address listed on Obria’s website for its Anaheim location is not a clinic but the St. Boniface Catholic Church. When I pulled up there one day in July, I couldn’t find any sign of an Obria outpost until a man watering the garden pointed me around back to a nearly empty parking lot, where I found an RV—Obria’s mobile clinic, parked within view of Anaheim High School, a prime target for its services, once students return in the fall.

After a long walk across the lot, I found Keith Cotton, the church and community outreach manager for Obria’s Southern California operation, and nurse Judy Parker sitting at a small card table under the RV’s awning. They were excited to see me. In its application for Title X funding, Obria said this mobile clinic would serve 500 low-income patients a year. Cotton and Parker clearly hadn’t had many, if any, patients that day.

Cotton, who I later learned got his start in activism working at evangelical minister Rick Warren’s Saddleback megachurch in Orange County, asked cheerily if I’d like an STI test. STIs are on the rise in California and elsewhere, and Obria is supposed to be combating them with its Title X grant. I chickened out at the prospect of having blood drawn. Instead, I asked if they could check me for a yeast infection. It’s the sort of ordinary, uncontroversial women’s health problem that should be treatable in a bona fide medical practice or at any Planned Parenthood, and fell under the heading of the well-woman care that Obria had promised in its federal grant application. Plus, I had some symptoms, so it was an honest request.

Cotton said Obria could help, but I would have to go to its free-standing clinic in nearby Orange. He and Parker walked me through the costs, explained the sliding-scale fee, and made me an appointment, which involved answering awkward personal questions about my health history and symptoms. Cotton and Parker were nice, but I couldn’t imagine a teenager having a conversation about STIs in the middle of this parking lot. Before I left, the pair kindly offered me recommendations for lunch, but not a single condom—among the best defenses against STIs, and a hallmark of legitimate public health prevention programs.

That afternoon, I dropped in at the Orange clinic. The only person in the waiting room was a Latina woman too old to need family planning services. I paid my $69 fee and filled out forms that asked surprisingly invasive questions I’d never seen on an OB-GYN or Planned Parenthood intake form, including “Who usually initiates your sexual activities?” Others, more standard, were about my abortion history, including how I would deal with a positive pregnancy test. And then there was this one: “If considering abortion, would you like Chlamydia/Gonorrhea testing today?” which seemed like a weird non sequitur. The form also asked patients to specify their religion. I signed a “Limitation of Services” that read: “Obria medical clinics does [sic] not perform or refer for abortions.” It didn’t mention contraception.

While I was filling out the paperwork, a smiling young Latino couple walked out of the exam area. They seemed excited to be having a baby. After a short wait, a nurse took my vitals and directed me into an exam room. Inside, the young woman’s sonogram still appeared on an ultrasound screen. On the wall, a scary chart claimed to show how “sexual exposure” goes up exponentially with every additional partner. If you’ve had 10 sexual partners, it indicated, you’ve really had sex with more than 1,000 people! I discovered later that the chart is a staple of Christian abstinence-until-marriage sex-ed programs like the one Obria runs.

Eventually I had to put my feet in the stirrups for an exam by Carol Gardner, a longtime Obria doctor and vocal anti-abortion advocate. There was no lab on-site, so Gardner gave me a prescription for an anti-fungal pill and said the clinic would call in a few days with my results. (A few days later, I found out I tested negative.) The staff and volunteers treated me kindly and with respect. Based on my one visit, I had to conclude that Obria’s Orange clinic was not fake, as the group’s critics have frequently alleged.

But good intentions are really beside the point. No one is suggesting that Obria shouldn’t be able to offer these kinds of limited health services to women who want them. The issue is whether it’s legal for Obria to take federal money for family planning and STI prevention but refuse to provide contraception and condoms or referrals for them. I couldn’t find a single public policy, academic, or legal expert who could answer that question, and HHS declined to comment. There’s also a much broader public policy question in play: Are Obria’s scant offerings, however thoughtfully they’re delivered, really the best use of limited taxpayer dollars dedicated to essential family planning services?

The 2019 grant to Obria provided funding that previously went to California’s primary Title X recipient, Essential Access Health. In 2018, Essential Access Health received about $23 million in Title X funds, which it distributed to more than 200 family planning clinics across the state, including city and county health departments and Planned Parenthood. In 2019, that budget was cut to $21 million; the other $1.7 million went to Obria. “We are very concerned that this will lead to low-income women facing more delays in access to the care they want and need to effectively reduce their risk of experiencing an unintended pregnancy,” said Essential Access Health CEO Julie Rabinovitz. “The changes this administration has made to the Title X program have been implemented to advance a political agenda, not public health.”

The entire annual Title X budget is a measly $286 million. To fill the unmet need of family planning services among low-income women, the Title X budget would need to more than double, to about $700 million a year, according to a 2016 study in the American Journal of Public Health. Reducing access to programs that provide more effective forms of contraception like IUDs or birth control pills all but guarantees more unplanned pregnancies and abortions.

Bravo insists that Obria clinics should get some of that federal funding because women want life-affirming choices for family planning. And some low-income women probably do want to learn natural family planning or find abstinence coaching, or what Bravo describes as “a second virginity.” But the Trump administration’s efforts to shift funding to Obria and groups like it aren’t just about religious freedom or broadening women’s choices under Title X. The conservative Christians in Trump’s administration would like to push low-income women to use places like Obria for family planning or reproductive health care. And ultimately, that’s no choice at all.