Bill Clark/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom via ZUMA Press

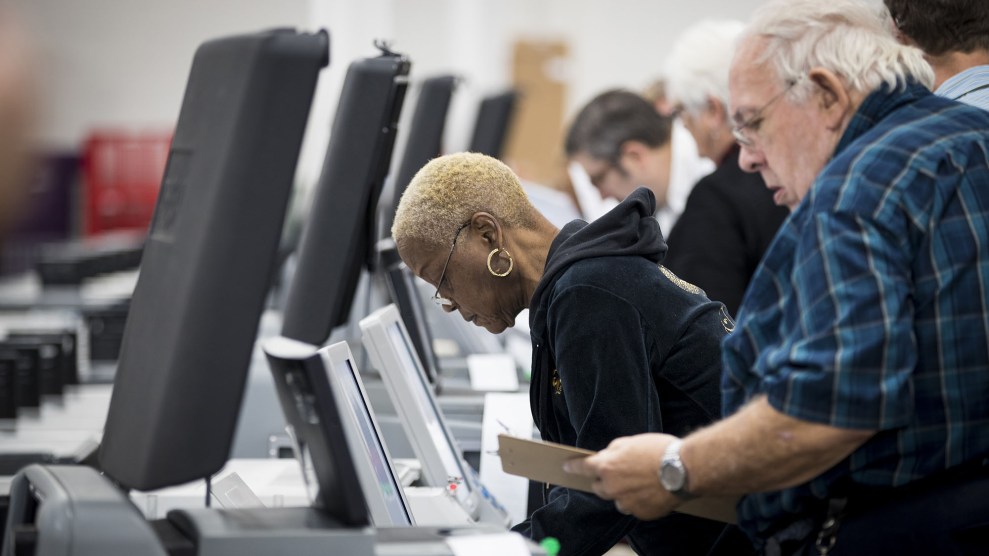

The heads of the country’s three largest election equipment vendors appeared before a congressional committee on Thursday for an unprecedented day of testimony. While they took pains to paint an overall positive picture of the state of U.S. election security, a group of election security experts who also appeared weren’t as optimistic, identifying significant security gaps despite recent progress.

The hearing was an opportunity to shine a light on the sometimes opaque election services provider world, which remains an active target of foreign meddling operations to this day. While the vendors’ chief executives—Tom Burt of Election Systems & Software, John Poulos of Dominion Voting Systems, and Julie Mathis of Hart InterCivic—all said they welcomed increased federal oversight and funding, they faced a range of questions on sensitive topics from lawmakers on their companies’ products and supply chains, their lobbying practices, and the reliability and security of so-called ballot marking devices, an increasingly popular piece of equipment that combines paper and touch-screen voting.

Committee Chair Rep. Zoe Lofgren, (D-Calif.) kicked off the hearing by citing an August 2019 article by investigative journalist Kim Zetter uncovering dozens of election systems connected to the internet, sometimes without officials’ knowledge. In response, Poulos and Mathis acknowledged their companies’ products use modems to transmit vote totals. Burt, of ES&S, claimed that hasn’t been a service in his company’s products since 2006. “That’s something that we may want to look at further,” Lofgren said, closing the line of questioning.

Burt was asked about ES&S’s lobbyists and their methods for securing contracts from state and local governments by Rep. Jamie Raskin (D-Md.), who raised an October story by ProPublica’s Jessica Huseman detailing the company’s aggressive sales practices. In September 2019, Philadelphia City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart said she found “serious flaws” with the way her city had awarded a $29 million contract to ES&S, following more than $425,000 in lobbying efforts and campaign contributions by the company as part of a six-year sales campaign. The company has defended its efforts, and argued its spending was properly documented. Burt told the panel that the company deployed lobbyists “to educate any of those involved about who we are as a company, the values we hold, and how we conduct our business.”

The executives acknowledged that their machines include hardware manufactured in China, a state of affairs that has been identified as a potential security risk, but argued that that was an unavoidable outcome of 21st century global supply chains. While the vendors’ said they would be willing to make their ownership structures public as a matter of transparency, such a requirement, along with other notable increased federal mandates or oversight, is unlikely anytime soon. In the wake of the Russian operation of 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has actively blocked most legislation related to elections in the upper chamber, taking the position they are state matters where the federal government has little role to play.

On Wednesday, researchers at the University of Michigan published a study examining the reliability of records produced by ballot marking devices, machines that allow voters to make choices on a touch screen before printing some form of a filled out, paper ballot that is tallied by optical scanner and then preserved for potential use in an audit or recount. While the systems are designed be easier and quicker than methods eschewing computers and provide greater accessibility to voters with disabilities, the researchers found the majority of voters failed to check the ballot put out by the machine to make sure it recorded their choices correctly, and that those who did usually failed to notice and report inaccuracies before handing their ballot over for scanning. Lofgren asked the vendors about an additional barrier that could keep voters from verifying printouts produced by the machines: the presence of bar or QR codes on the records to facilitate optical scanning, which are unreadable by humans. Mathis, of Hart, said her company’s technology does not use bar codes but the other two executives confirmed ES&S and Dominion products do.

While the Michigan researchers noted error-detection rates improved when poll workers specifically asked voters to review their ballots, their results led them to conclude that for now hand-marked paper ballots for those who can use them are the safest choice. But suggestions that the machines might be only made available to voters who would have difficulty filling out ballots by hand were rebutted by Juan Gilbert, a University of Florida computer science professor and elections expert, who told the committee that establishing a flawed system for those with disabilities not only instills a “separate but equal” connotation but also makes overall election security more difficult.

“If we design these machines so they’re only used by people with disabilities, an adversary finds that as a happy day,” Gilbert said. Universal design, where all voters use the same system, allows for security strategies to be more uniform and effective, he argued. He said that further focused study is needed to improve the technology, and argued that requiring an all hand-marked paper ballot system in the face of cyber attacks would be “the same as saying we had an accident on the highway and people unfortunately died so we should return to horses and carriages.”

The committee also heard from two other election security experts who reiterated they remain worried about election machine vulnerability. Liz Howard, counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program and a former deputy commissioner at Virginia’s Department of Elections, warned that election vendors “play a critical role in our democracy but have received little or no congressional oversight.”

Matt Blaze, a Georgetown computer scientist and a prominent expert in the field, said that election infrastructure—not only used to cast votes, but to register voters, design ballots, and report results—”has proven dangerously vulnerable to tampering and attack,” and suggested policymakers should devote more attention to such backend systems, which can offer hackers more centralized targets. Despite gains made by the vendors and the tens of millions spent on new balloting machines since 2016, Blaze argued that “it’s a widely recognized, really indisputable fact that every piece of computerized voting equipment in use at polling places today can be easily compromised” in myriad ways. “The vulnerabilities are real, they’re serious, and absent a surprising breakthrough in my field—which I would welcome but I don’t see coming soon—probably inevitable.”

Blaze said that machine-aided elections can be safe and reliable as long as voter intentions are accurately recorded on paper then checked in rigorous post-election audits. Unfortunately, Blaze noted, only a handful, but growing, number of states employ what’s known as a risk-limiting audit, the gold standard among election security experts that harnesses statistics to randomly select ballots for manually inspection and comparison against the machine tallies.

“Just as we don’t expect the local sheriff to single-handedly defend against military ground invasions, we shouldn’t expect county election IT managers to defend against cyber attacks by foreign intelligence services,” Blaze said “But that’s precisely what we’ve been asking them to do.”