You don’t see a lot of political rallies like Bernie Sanders’ election-eve extravaganza at the University of New Hampshire. It was the first campaign event I’ve ever been to where a candidate’s staffers had to struggle to get people to stop crowdsurfing. It was also the first political event I’ve been to where cops rushed the stage to confront one of the headliners.

Unusual, for sure. But what was so unprecedented about the event on Monday at the university’s ice-hockey arena, officially called the “Bernie Beats Trump Concert and GOTV Rally,” was the sea change it portended. In front of 7,500 supporters, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a few people dressed up as fire emojis, and The Strokes, Sanders was making a statement not just about how well he would do in the primary here, but what kind of victory it would be.

Listen to Tim Murphy describe Bernie Sanders’ journey to frontrunner status, from inside the roaring Sanders celebration party, on this special New Hampshire primary edition of the Mother Jones Podcast:

New Hampshire would make history, he predicted. Sanders would deliver the highest turnout in the history of the first-in-the-nation primary, and he would win on Tuesday. And then he would just keep going down the line. He’d win California on March 3, and then the Democratic nomination, and then in November he’d win the whole damn thing. Sanders was getting ahead of himself, but it’s not such a crazy prospect right now. After his victory on Tuesday, Sanders has become something that for most of his political career would have seemed like a joke: Right now, Bernie Sanders is the closest thing the Democratic presidential race has to a frontrunner, and he’s done it with a campaign operation that is its own kind of statement of the country he wants to build.

Sanders’ narrow win in New Hampshire capped one of the wildest weeks in the recent history of the Democratic party, a chaotic seven days that blew up the equilibrium of the race, put the previous frontrunner on the ropes, injected fresh paranoia and ill will into what up until then had been a fairly mild contest, and left the nominating system itself a broken mess.

When I first caught Sanders in Manchester on Thursday afternoon, at a campaign office off a shopping center north of downtown, he was as close to pissed as the post-heart-attack, kindler-gentler Bernie seems to get. He, not Pete Buttigieg, was the true victor in Iowa, he declared; he trashed the caucus process and the fallout, said that it had been “very unfair” to him personally, and that he was looking forward to being in a place that calculates its winner by adding up votes.

Some voters I spoke to in New Hampshire were less kind. It was a “clusterfuck,” I was told in West Lebanon. Sanders supporters raised questions about the app that had failed on caucus night, alleging that perhaps Buttigieg himself was somehow involved.

And it was a kind of existential debacle. Campaigns poured tens of millions of dollars into the state, logged thousands and thousands of man hours organizing there. Some candidates fucking moved there, and some candidates dropped out when they failed to gain traction. I took a stats class in college and one day a stack of our exams was set on fire by a disgruntled grad student. We would never truly know how well we did. Iowa was sort of like that.

But amid all the chaos, there was a lot about Iowa that was knowable. As he would do in New Hampshire, Sanders spent the final days of that race boasting about turnout. He would go into claustrophobic campaign offices in college towns and ag centers, and walk outside to address the spillover. Sanders didn’t stick around for the Super Bowl at his own Super Bowl party—his “Super Bowl…thing,” he called it—but he stuck around long enough to say he wanted “to create the highest turnout in the history of the Iowa caucus.” It was a promise in service of an argument; in turning out his voters, he would deliver up for the party and the media an irrefutable argument for his own electability.

That turnout didn’t materialize in Iowa—it was about on par with 2016—though turnout in New Hampshire came pretty close. So far Sanders hasn’t expanded the electorate quite like he’s promised to do, and his success in the general election (if he makes it that far) could hinge on his capacity to change that. But he’s engendered real loyalty in his supporters that has helped him weather an up-and-down campaign. No one raises more money from more people, and in the first two states, no one has been able to summon more people to do the work on the ground of getting out the vote for him. Their work meant that while Sanders didn’t realize all the gains he’d envisioned, he didn’t fall off either like some of his colleagues.

Sanders set out to build and consolidate his coalition by “centering,” as Ocasio-Cortez likes to put it, the kinds of working people who stand to benefit from his economic agenda. In October, I caught Sanders at a youth enrichment center outside Charles City, Iowa, the same weekend he’d led a series of high-profile rallies with Ocasio-Cortez—big flashy events at an arena, a college campus, and a conference center. The man who introduced him, to a crowd of a few dozen people off a two-lane road, wasn’t a nationally prominent politico or a state rep or even a county commissioner. His name was Steven Zimmer, he told the room. And he was a gas station clerk at Hy-Vee.

The local politics website Iowa Starting Line reported that Sanders’ Iowa field team included “an Olive Garden server in Iowa City, a Bettendorf brewery worker, a North Liberty Hy-Vee clerk, an Iowa City cashier at Lowes, a St. Kilda’s bartender from Des Moines, an Ottumwa security guard and a records store worker from Sioux City”—and relied on those staffers to organize their own networks with meetups and other events. Sanders featured Amazon warehouse workers in advertisements and crashed a Walmart shareholder meeting to advocate on behalf of employees, who rewarded his work in their own way—Walmart is one of the top employers of Sanders small-dollar donors.

The campaign itself, in other words, was a reflection of the message. This was the operation that staked out a meat processing plant in Ottumwa at midnight in the hopes of persuading enough voters, some of whom were immigrants from Ethiopia*, to turn out for him at special mid-day satellite precinct—the campaign’s commitment to principle merging with an attention to detail. In Waterloo, Iowa, I met a field organizer for a rural county whose previous job had been loading tractor trailers at a Target distribution center. Now he was at a union shop—the first presidential campaign to have unionized, in fact. Working for Sanders, he told me, was the only job he’d ever had where he could actually use his health insurance.

Such an ethos instills a real loyalty among his supporters. Some of the same volunteers who descended on Iowa to knock doors for him moved on to New Hampshire a week later. At a canvassing kickoff in the small town of Plymouth, an hour north of Manchester in the White Mountains, nearly everyone I spoke with was from out of state—a professor from New York City, a student from Westchester, a supermarket seafood clerk from New Jersey. They had organized themselves, chartered buses and carpooled, and kept going up I-93 when the office in Manchester told them the city was full. Sanders brought on stage his campaign director in the state, Shannon Jackson, to rattle off the stats. They’d knocked a door every four seconds, he said.

In the back of the room I met Sam Jaffe from Bushwick, who had arrived in the state after five days in Cedar Falls, Iowa, where he’d help deliver Black Hawk County (but failed to convert his host).

“I would never go up to New Hampshire in February to canvass for anyone else,” he said.

He had to skip Nevada, though—he was running out of vacation days.

Sanders emerged by holding his own while the man who was supposed to beat him fell apart. The Vermont senator never subscribed to this view, of course, but heading into Iowa, there was a working theory that the Democratic primary might end up rather tame after all. Biden led the polls there for months in the summer and again in the final weeks, trotted out key endorsements—Reps. Abby Finkenauer and Cindy Axne, Tom and Christie Vilsack—and threw the full weight of his resources into the state. Perhaps Biden would win Iowa, and then he would win New Hampshire, and then he would win Nevada, and of course he would win South Carolina, and then it would soon be over. He’d break the back of Sanders campaign early on, shed the pesky Buttigieg and Elizabeth Warren, and render unnecessary the whole notion of Michael Bloomberg’s centrist airlift. This was a season of optimism, and it’s never more in abundance than when professional Democrats are trying to paper over the weaknesses of a flawed candidate.

Alas.

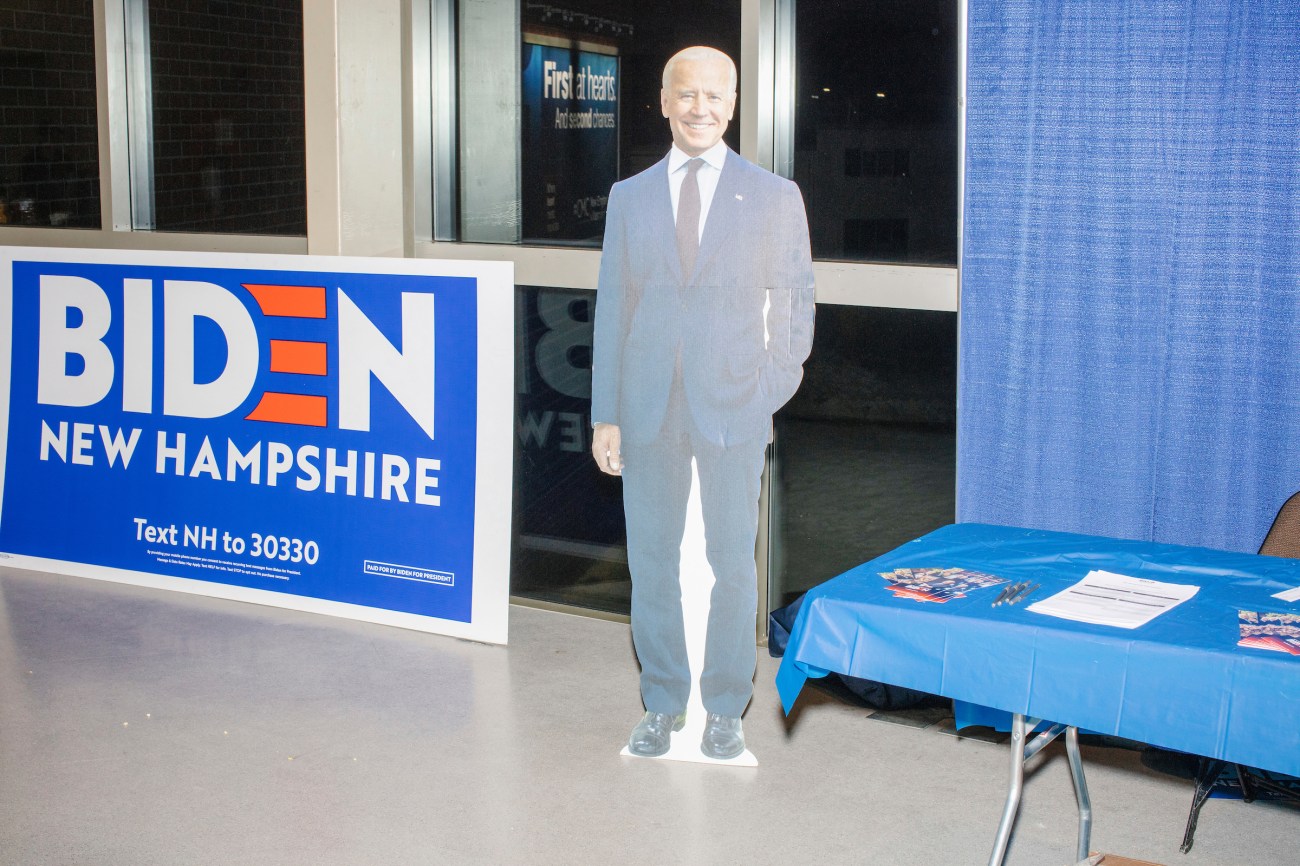

Joe Biden: the cardboard candidate.

M. Scott Brauer for Mother Jones

Biden didn’t just lose; he lost in a way that gave the lie to the most insistent argument he’d offered for his candidacy—electability. Whatever that word meant, exactly, it was the subject of ads and stump speeches and debate monologues. It was an effective argument, up until the moment it wasn’t. Campaigns are still powered by people, and in Iowa, Biden’s lack of an organization was exposed. The campaign had to scramble to bring volunteers in from out of state to manage its caucuses and knock on doors. The Washington Post reported that some of them simply didn’t show up. On caucus night, Biden failed to hit the viability threshold in precinct after precinct across the state.

Biden switched gears a bit in New Hampshire. He started to emphasize what he would do in office a bit more, and he took some shots at Buttigieg (whom he had largely ignored) and Sanders. He called the Iowa results a “gut punch” and promised supporters they’d get a feistier Biden this time around. Nobody messes with Joe! Still, it was tough going. He went home midweek to sleep in his own bed, and his crowds were smaller when he came back. (Amy Klobuchar’s just kept growing.) At Saturday’s McIntyre–Shaheen 100 Club Dinner, a party fundraising cattle call that filled an arena in downtown Manchester, Biden supporters were almost invisible, cloistered in a corner and struggling to start the simplest of cheers.

As the campaign spiraled this week, Biden ditched his election-night party in Nashua for an early trip to South Carolina. Advisers played up the whiteness of Iowa and New Hampshire in explaining away their defeat. But that was never supposed to be his problem. Biden had previously said he could win both of those states, and he has built his political brand—a no-malarkey Irish-Catholic kid from Scranton—around winning back older and working-class white voters in swing states. His performance raised the question: how exactly?

Pete Buttigieg finished a close second in the New Hampshire primary.

M. Scott Brauer for Mother Jones

Elizabeth Warren, Sanders’ main rival for the liberal vote, stumbled to a fourth-place finish.

M. Scott Brauer for Mother Jones

Skepticism about Biden’s ability to take on Trump—his selling point for months—haunted him in New Hampshire. I heard it and over and over as I spoke with undecided (or recently decided) voters in line to hear Buttigieg. As one voter told me before a town hall in Lebanon: “At one point I thought he was the most likely guy to get elected, but now I don’t know.”

Now the campaign enters a much larger and far stranger map. On Saturday, while the rest of the field braved the icy roads of New Hampshire, Bloomberg lurked just out of the picture. As polls showed him gaining in the critical Super Tuesday states of California and Florida, and drawing close to even nationally with Biden among African-American voters, his campaign held a frenzy of organizing events in Massachusetts, which votes on March 3. That’s the strangest thing about the Democratic primary so far: the idea, proposed by Bloomberg, that none of it actually matters.

The paths by which Sanders and Bloomberg could win the nomination have always depended on the scenario that’s played out so far. Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar will have their say, of course, and Biden is drawing a line in the sand down the road. But right now it’s a collision course between two people who have never held elected office as a Democrat—a lifelong independent who has shattered small-dollar fundraising records and trashes billionaires, and a Democrat-turned-Republican-turned-independent-turned-Democrat who has shattered spending records simply by being a billionaire. If it holds, it would be the starkest contrast the same party has offered since the civil rights re-alignment.

You can get lost in the numbers and the war-gaming, the endless hypotheticals spiraling off an extremely small set of data points (thanks again for that, Iowa). Being a frontrunner isn’t always what it’s cracked up to—just ask Joe Biden. But it’s worth taking a step back to remember that this is Bernie Freaking Sanders we’re talking about.

In 1969, a few years before Sanders stood up at a local meeting of the Liberty Union Party in Plainfield, Vermont, his 2-year-old son Levi in his arms, and volunteered to run for office, he wrote an essay for a short-lived alternative newspaper called the Vermont Freeman. Sanders was trying to make a go of it as a freelance writer at the time, and he wasn’t very good at it. His writings in the Freeman, in which he criticized compulsory public education and suggested that some women fantasize about rape, have been a headache for him as he’s risen in national politics. He was in a weird place, personally and professionally, and the focus of his politics has, truly for everyone’s good, moved from the psychoanalytic to the structural. But there was a thread in his writing back then that sounds familiar today. He was painting a picture of change.

“The Revolution is coming and it is a very beautiful revolution,” he wrote.

“The revolution comes when young people throughout the world take control of their own lives and when people everywhere begin to look each other in the eyes and say hello, without fear. This is the revolution, this is the strength, and with this behind us no politician or general will ever stop us. We shall win!”

A lot has changed in four years, to say nothing of 51, but this vision hasn’t. In New Hampshire, as in Iowa, his ads feature a line from his speech in New York City last October, his first rally since suffering a heart attack—what his supporters call the #BerniesBack speech. “Take a look around you,” he said, “and find someone you don’t know,” and then ask yourself: “Are you willing to fight for that person as much as you’re willing to fight for yourself?”

On stage at the rally in Durham, it was an idea invoked by the closest thing he has to proof of concept, Ocasio-Cortez, whose rapid ascent reflects the growth and reinvention of the movement over the past four years, from a coalition doomed by its demographics (or at least by perceptions of its demographics) to the No. 1 choice of non-white Democrats, according to a Monmouth University poll. While thousands watched in Durham, far more tuned into the livestream of the event, which the campaign had turned into a telethon of sorts, posting the names of contributors as their dollars rolled in—$11 from Juliette P., $12 from Adam C., $3 from Tse P.

People listen as Bernie Sanders speaks at Saturday’s “Our Rights, Our Courts” forum in Concord, New Hampshire.

M. Scott Brauer for Mother Jones

The show wrapped, an hour later, with an appropriate dose of chaos. The Strokes’ frontman, Julian Casablancas, was upset that the second half of their show had played out with the overhead lights of the arena turned on. This, he told the crowd, was the police’s fault, and so as the fundraising ticker crept closer to the target, the band broke into the familiar chords of “New York City Cops.” “Holy crap they’re doing it,” someone wrote in the live chat.

One last crowdsurfer rode the wave and rolled onto the stage, dropping in front of Casablancas, and when a security guard stepped in to haul the man off, Casablancas threw up his hands.

“Come up on the stage, y’all!”

The front row obliged—the barriers holding them back had been removed in an unsuccessful bid to stop the crowdsurfing—and for the final minutes, the crowd and the band were as one, the people had taken control, the establishment had been overthrown. As they approached the final chorus there was a cop at Casablancas’ side, gesturing, trying to get his attention, but the band just kept playing, until the last chord hit and he turned and walked off. This was the revolution, and for the moment, at least, no one could stop it.

*Correction: This story originally misidentified which country workers in Ottumwa had emigrated from.