Pema Levy

If last week’s Democratic caucuses in Nevada put workers’ power front and center, with the legendary Culinary Union securing praise from all the candidates and turning out members to casino-based sites up and down the Las Vegas Strip, striking South Carolinians are determined to show the country the opposite: the struggles of toiling in poverty in the state with the lowest union participation in the nation.

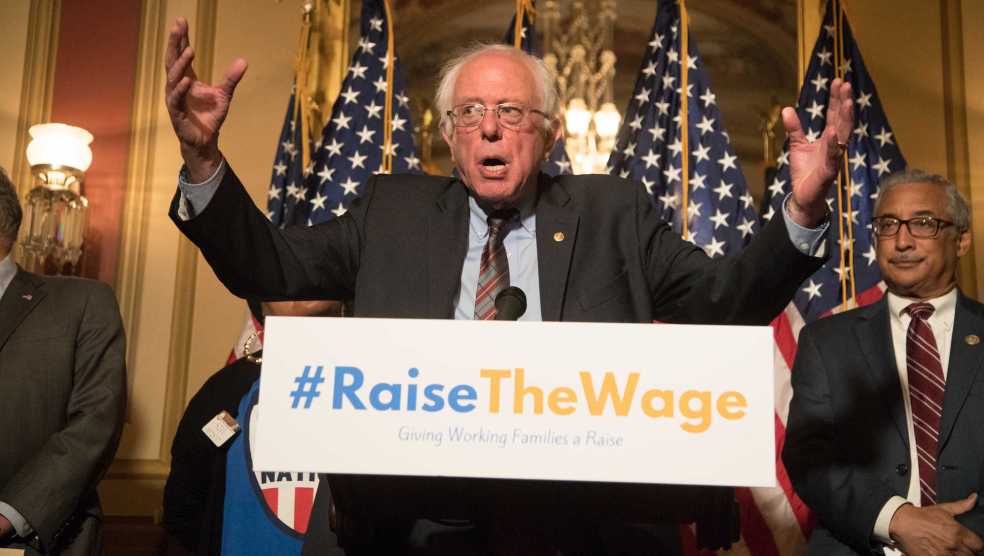

Workers involved with the Fight for $15, a national movement of thousands of fast food employees in South Carolina and around the country fighting for a $15 minimum wage and union membership, held a rally on Monday, then marched to a local McDonald’s franchise that was on strike. They invited the Democratic candidates competing in Saturday’s primary to join them to spotlight their cause.

“We want to be part of the conversation,” says Terrence Wise, a McDonald’s worker in Kansas City, Missouri, who traveled to his native South Carolina to help lead Monday’s actions. “We’re being strategic.”

Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s campaign sent its top surrogate in the state, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.), a freshman member of Congress who has spent several days boosting Warren in South Carolina, particularly among African American women like herself. She connected with the protestors in away that emissaries dispatched by rival campaigns could not.

Speaking to the majority black crowd of protesters, Pressley described their fight as the next chapter in the civil rights battles of the 1960s, a movement she said was not yet over. “Dr. King said, ‘What does it mean if we desegregate a lunch counter but you can’t buy a hamburger at it?'” Pressley said in her remarks. “Tell it!” one protester shot back.

“I know it’s customary for folks to come before you and say they want to be a voice for the voiceless,” Pressley continued. “But the truth of the matter is that those of us who are victims of structural racism and systemic oppression and are marginalized, we are not voiceless: what we are is unheard.”

Her words echoed the workers’ goal of seizing part of the attention focused on South Carolina this week, with particular hope their struggles will take center stage at Tuesday’s Democratic debate. South Carolina has one of the highest poverty rates in the country and, not coincidentally, the lowest union participation rate at just over 2 percent of workers. It is one of just five states—the others are also in the South—that has never adopted its own minimum wage. It is also not a coincidence, as a speaker from an Atlanta-based group named Black Voters Matter said, that South Carolina was the first state to secede from the union at the outbreak of the Civil War. South Carolina’s place near the top of the Democratic primary calendar gives the activists a brief window to be heard on a national stage, and to situate their struggles in the context of the United States’ untoppled racist structures. As one of the banners hoisted at the front of the rally read “Racial Justice = Economic Justice.”

In South Carolina, “racism is baked into the economy,” says Wise, when asked why what was happening in the state felt so different than the story of triumphant unionism in Nevada. “That’s the reason there’s no minimum wage.”

Multiple candidates have met with Fight for $15 members in South Carolina, including Warren, Pete Buttigieg, and Bernie Sanders, along with former contenders Cory Booker, Julián Castro, Kamala Harris, and Beto O’Rourke. On Monday, the Sanders campaign sent a last-minute surrogate in Susan Sarandon. “I left my New York bubble” to see what was going on, Sarandon told a welcoming crowd, looking, in her embroidered leather jacket, like she really didn’t belong in a soggy field in Charleston.

As the protesters marched from the rally to the McDonald’s a few blocks away, they were joined by Buttigieg, who has struggled to secure the support of African Americans. While Buttigieg has met and marched with these workers before in South Carolina, he was met at the restaurant by a small group of counter-protesters who questioned the South Bend mayor’s sincerity. “Pete can’t be our president,” they chanted, “Work with Fifteen in South Bend.” The group marching beside Buttigieg launched into one of the movement’s chants in response: “We work, we sweat, put fifteen on our check.” After two local fast food workers spoke, Buttigieg gave remarks for less than a minute, struggling to be heard over his opponents. Then he hurried off into a black SUV, flanked by aides and hounded by reporters and antagonistic protesters.

Pete Buttigieg joins striking fast food workers in Charleston on Monday.

Pema Levy/Mother Jones

Most of the workers weren’t fretting over who might have looked out of place or whom they suspect may be insincere. They just wanted, as Pressley put it, to be heard. And on Monday, it was Buttigieg’s presence that brought about two dozen national reporters, photographers, and television crews to the strike. After Buttigieg had left, the protest had died down, and the press had moved on, Taiwanna Milligan, a McDonald’s worker, leaned against a wall, so tired she could barely speak. She had introduced Buttigieg after telling her own story about trying to earn enough as a single mother to take care of her 12-year old son with sickle cell anemia. The candidates “are here and they’re running for president,” she said, “our voices are being heard.”

Milligan’s exhaustion faded momentarily as she talked about what she hoped to ask the candidates when she attended Tuesday night’s debate as part of a group of Fight for $15 activists: How will you secure a living wage and a union for all workers? “Here our rent is as much as our check,” she said. “I’ve been homeless.” When, after Saturday, the primary is over and the candidates have moved on to other states, she plans to keep striking. “This is a really serious situation for me,” Milligan says, “because I can’t live like this.”