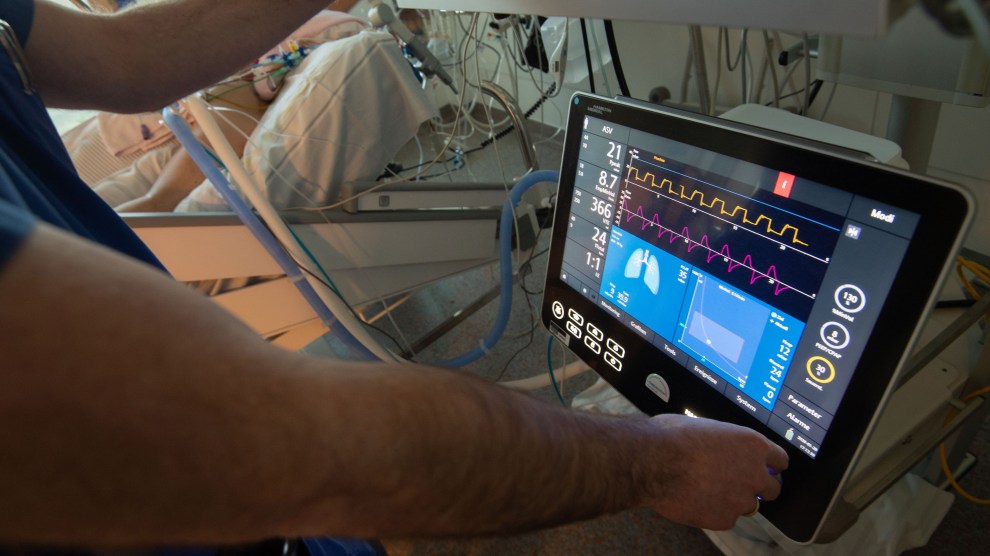

Marijan Murat/DPA via ZUMA Press

In the past days and weeks, health care experts have focused on a horrifying reality: the acute shortage of ventilators, a common medical device that is necessary to help patients with serious respiratory diseases, such as COVID-19, breathe. There are an estimated 160,000 ventilators in hospitals throughout the United States. (The numbers are not precise.) That is far from the amount that might be needed, and without ventilators people with the worst cases of COVID-19 will die.

The media have been covering the ventilator deficit and efforts to increase production of the device. But there is a parallel story that has drawn less attention: the availability of the health care professionals who can insert and operate the ventilators. In most hospitals, the use of ventilators is managed by respiratory therapists who tend to work in intensive care units. These are specially trained clinicians who attend two- or four-year programs and who are licensed within their states. Without an army of professionals to operate the ventilators, having enough machines does no good. Are there enough of them?

To learn more about this, I spoke with Thomas Kallstrom, the chief executive officer of the American Association for Respiratory Care. Kallstrom, who used to be a practicing respiratory therapist in the Cleveland area, says that a survey conducted by his outfit five years ago determined there were about 155,000 respiratory therapists in the United States, with a vast majority of them working in ICUs. Should hundreds of thousands of Americans end up requiring ventilators in a short period of time, this work force could be stretched thin.

Kallstrom notes that on average a single respiratory therapist can manage ten patients at once. But that’s in normal times. “If we have to ventilate 750,000 people, we will have a situation we can’t handle,” Kallstrom observes.

Working closely with infected patients, respiratory therapists are also at great risk of becoming infected themselves by the coronavirus, and such transmission could cut down their ranks. Making matters more dire, some facilities may only have a handful of licensed therapists. One respiratory therapist who works in a medium-sized hospital on the East Coast, who asked not to be named, tells me that she is one of just three respiratory therapists in her facility.

Ventilators are needed in advanced and serious stages of respiratory disease, when lungs are not functioning sufficiently to supply the body with the oxygen it needs to survive. A respiratory therapist “intubates” the patient—that is, he or she directs a tube past the vocal cords and toward the lungs. The device then balloons out and starts pumping the lungs. The respiratory therapist has to determine the appropriate settings for the device, based on body size, blood gasses, and other factors. The ventilator and the patient subsequently have to be monitored by the therapist, around the clock. These visits can take a brief amount of time, though complicated cases can require much more.

Usually, a patient must remain on the ventilator for days, if not a week or longer. And for this stretch, he or she is sedated. “I was on a ventilator for a respiratory disease a few years ago,” Kallstrom recalls, “and I don’t remember the experience. I just woke up.”

Should a shortage of respiratory therapists occur, there are options, Kallstrom explains. A great many respiratory therapists are Baby Boomers, and a large number of them have retired in recent years. Hospitals could begin reaching out to the retirees and asking them to return, if only to support the non-retired therapists and enable them to concentrate on ventilator management for COVID-19 patients. Students currently enrolled in training programs to become respiratory therapists could be used in a similar fashion. And in a jam, nurses and doctors could certainly be trained to work the ventilators. But, of course, they will be overwhelmed with other tasks.

On another front, state legislatures and the federal government could move to ease or end the restriction that prevents respiratory therapists from working in states other than the ones in which they are licensed. Kallstrom notes that Vice President Mike Pence, who heads the federal coronavirus task force, has said that this restriction on clinicians will be lifted, but he adds, “We’re still trying to get a clear signal on this. It will behoove the states to allow that to happen.” This will permit respiratory therapists to move across state lines to help areas with the most desperate need.

At this stage, Kallstrom is not predicting doom. But he states the obvious: hospitals, the medical community, and the government need to start preparing for the worst as quickly as possible. And that includes thinking about who will be operating life-saving ventilators.

“Not many people know what respiratory therapists do,” he says. “We want to make sure Americans know they are on the frontlines in this crisis. It sounds gross, but they will take the spit to the face, as they manage the coronavirus patients. They are heroes. But they are unsung heroes.”