An activist rallies drivers in a parking lot before Tuesday's anti-ICE car protest.Molly Stuart

Downtown San Francisco should have been quieter than ever, since most of the city has been quarantining for weeks due to COVID-19. But on Tuesday morning, the streets echoed with more noise than a typical rush hour, as a long caravan of cars blaring their horns inched toward the Immigration and Customs Enforcement building, demanding the release of immigrant detainees who are highly at risk during the pandemic.

Noisy caravans simultaneously moved through Sacramento, Los Angeles, and San Diego, employing a tactic that has caught on nationwide as a safe way to voice political dissent in a time of social distancing: protesting from your car.

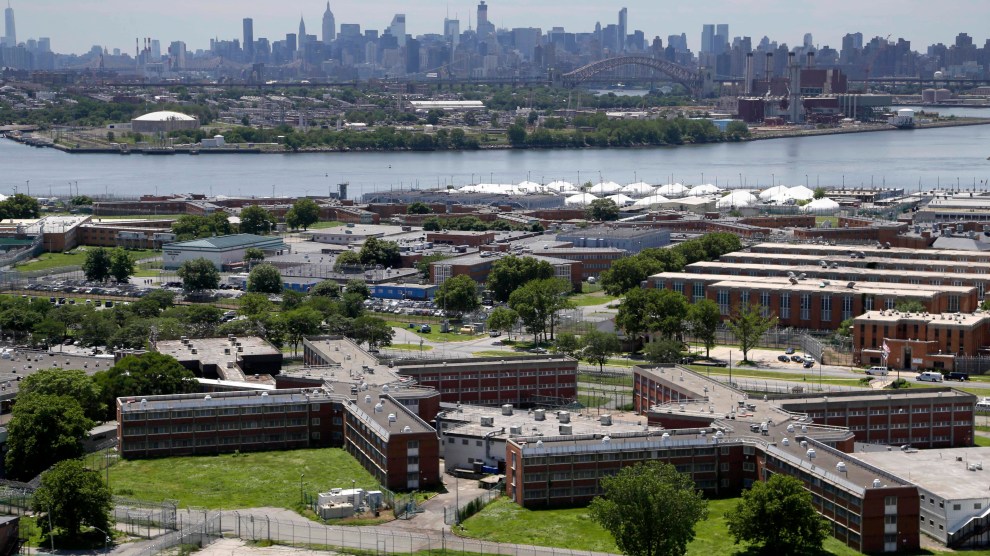

Many activists credit Never Again Action, the national network of Jewish people and allies, with inspiring the idea after they mobilized as many as 100 cars to surround ICE’s Hudson County detention center in New Jersey on March 22. Since then, protest caravans have appeared in Philadelphia, Chicago, and throughout California, calling for rent forgiveness, freedom for prisoners in overcrowded jails, better funding for health care workers on the pandemic’s front lines, and removing President Trump from office.

Yesterday we surrounded an ICE Detention Center in NJ. We won’t let COVID turn detention centers into death camps.

We need your help to do this across the country. We have to pressure 50 Governors to act to protect ALL of the people in their states, no exceptions #ReleaseThemNow pic.twitter.com/9KeCo500eL

— ✡️ Never Again Action ✡️ (@NeverAgainActn) March 23, 2020

The tactic isn’t necessarily new—automobiles were used to hold up traffic during Black Lives Matter protests throughout the last decade, and even played a role in the Montgomery bus boycotts of the 1950s. But by insulating passengers at a safe remove from others, cars have taken on new relevance in the age of the coronavirus, when people can’t otherwise be in the streets.

“Of course there are digital actions,” says a member of Never Again Action, which organized the recent San Francisco protest. “But there’s something about an in-person action that wakes people up to the urgency. We wanted to protest in a way that couldn’t be ignored, since detention facilities aren’t in broad daylight and we don’t alway know what goes on inside.”

Never Again Action draws parallels between modern immigrant detention and the historic persecution of Jews, a connection they say grows more pressing by the day as overcrowded and unsanitary conditions threaten to turn ICE facilities into “death camps.”

An activist on San Francisco’s waterfront prepares for a car protest.

Molly Stuart

“We’re doing what we wish that bystanders had done for our ancestors, which would have prevented a lot of death and suffering if a critical mass of people had noticed and taken action,” says one organizer, whose car blasted Beyoncé’s “Freedom” repeatedly throughout the two-hour protest. I trailed somewhere behind, alone in my Ford. Snaking through city streets in such a long caravan felt chaotic, but the dozens of cars attained critical mass at times, such as when they circled the block around City Hall.

Though the group defied stay-at-home orders, “I’d argue that protest is an essential activity,” te organizer says. “We’re ringing the alarm about something that could become a greater public health emergency.”

“Anne Frank didn’t die in a gas chamber,” said a sign taped to one car at the protest. “She died of typhus in a detention camp.”

Besides the danger they pose to people inside, infection hotspots like ICE facilities, prisons, and jails can rapidly spread the virus to local communities, through guards and others who move in out of such places.

Related concerns inspired Norma Orozco to attend a car protest in Oakland last week. After noticing that the Alameda County sheriff added an $85 million request to expand the police force at around 8 p.m. on the night before a county Board of Supervisors meeting, Orozco, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, and other local anti-incarceration groups mobilized to have a car-based presence when the meeting started at 9 a.m. the next day.

As county supervisors met in person to vote on their agenda, Orozco circled the building with a dozen other cars before parking in a place visible through the meeting room’s windows.

“We wanted to let the supervisors know that we were still watching and paying attention to what’s going on,” says Orozco, calling the sheriff’s last-minute request a “cash grab” made strategically while advocates were busy trying to provide sanitary supplies to inmates and release as many as they could. The sheriff’s office said that his request was not coronavirus-related; the protestors called for money to be diverted to local hospitals instead.

Cars circled the Alameda County Board of Supervisors meeting to protest a budget increase for their sheriff.

Brooke Anderson

That car protest seemed to be a success, as the supervisors postponed their vote to allow for weeks of public comment on the sheriff’s request. Those driving against ICE, however, continue to play the long game.

Tuesday’s statewide protest in California dovetailed with earlier pleas by San Francisco District Attorney Chesa Boudin, who called on Gov. Gavin Newsom to use emergency powers during COVID-19 to suspend ICE facility contracts and release detainees. The governor’s office replied that only the federal government could do so. Yet organizers with Never Again Action say they will keep applying pressure at all levels of government.

“We are trying to stop preventable deaths before it’s too late,” says the organizer, adding that the turnout of more than three dozen cars, and even more in other cities, was a pleasant surprise. “When we’re all feeling isolated, it’s really important to express dissent in a collective way,” he says.

Ruth Robertson, who is 67, drove out to represent the Raging Grannies Action League, who have protested immigrant detention policies for years. But “the last time we were in the streets was March 7,” says Robertson, before the pandemic became grave. “We’ve been itching to get out in the streets again, and this is the best way to do it while still being safe.”

Wearing an N95 mask behind the wheel, and a matronly apron overflowing with buttons, Robertson said she was taking pains not to contract the virus. “I’ve been getting my food and produce delivered,” she said. “I’m staying inside, except for today.”

Outside the Los Angeles Metropolitan Detention Center where anti-ICE protesters are staging a car horn protest to demand ICE release all of its detainees for fear of coronavirus outbreaks while in custody.

Signs say, "Release them all," "Detention is deadly," and "Fuck ICE" pic.twitter.com/wyIrxDXrsP

— Julio Rosas (@Julio_Rosas11) March 31, 2020