On the night of the 2020 Iowa caucuses, Brad Parscale, President Trump’s campaign manager and technology guru, arrived at an elementary school on the outskirts of Des Moines. With attention focused on the hard-fought Democratic contest, Trump sought to steal a bit of the spotlight by displaying total dominance over his no-hope opponents. As part of the process, each GOP candidate had dispatched someone to caucus sites around the state’s largest city to speak on their behalf. For some 100 voters in suburban Urbandale, it was Parscale.

A 6-foot-8-inch Texan with a red Viking beard, Parscale had been plucked from obscurity in San Antonio to serve as a key digital staffer on Trump’s 2016 campaign. His pitch to the crowd included observations highlighting his now firmly established place in the president’s inner circle, according to Lucy Caldwell, who was present that night. He compared flying on Trump’s jet with White House trips: The private plane was nicer, but he preferred the food on Air Force One, opening his navy suit jacket to show his waistline. He described attending the Super Bowl, just the night before the caucus, with Trump kids Eric and Don Jr., as one of the “perks of the job.”

All this struck Caldwell as off-key. She was the campaign manager for one of the president’s Republican challengers, a tea party ex-member of Congress turned prolific anti-Trump tweeter named Joe Walsh. At the end of Parscale’s speech, she watched as he placed a red cap reading “Keep Iowa Great” on a child’s head, feeling like she was witnessing some bizarre ritual. “Suddenly several Trump staff appeared holding these hats, and Brad and the staff walked around placing these hats on these children,” Caldwell recalled. “It was weird.”

While Parscale has been heralded as a digital demigod for serving microtargeted Facebook ads pushing border walls and allegations of “fake news” to the president’s cultish fans, his caucus night remarks were in keeping with someone whose history evinces plenty of ambition, but little interest in the hot-button topics that power devotees of the MAGA movement. Instead, Parscale was enunciating a different set of Trumpian priorities, ones to which he assuredly subscribes. Private jets and Super Bowl suites are a natural part of Parscale’s pitch to voters because the perks help explain why he works for the Trumps: the wealth, the fame, the spot inside the insular club that is the first family, where he has expertly ingratiated himself. Who wouldn’t want a hat to signal membership in this profitable club? But if you’re not born a Trump, the only way to stay a member is to keep winning.

Parscale’s abilities are particularly critical now that the coronavirus has reshaped the political landscape. Traditional rallies and face-to-face campaigning aren’t possible, making the digital battlefield where Parscale cultivated his reputation even more important. A reelection message that was likely to rely on a strong economy must adapt to a new, harsh reality and make a case for Trump’s handling of the pandemic and its attendant economic catastrophe. But whether or not he can adapt and pull Trump over the finish line this November, Parscale will have gotten rich and famous trying.

Parscale first entered the first family’s orbit by securing a bid to build websites for the Trump Organization in 2012. Running a web business in San Antonio, Parscale knew that getting in the mogul’s good graces mattered more than the first paycheck, so, according to the Washington Post, he lowballed his bid at $10,000 and told Eric Trump the family could get a refund if they weren’t satisfied. The Trumps directed hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of work his way over the next five years, leading Parscale to credit his patrons with transforming him from a once-scrappy entrepreneur into a Texas success story.

When Trump began his presidential bid in 2015, Parscale built the campaign site. When Jared Kushner felt that the candidate’s team lacked an online strategy, he called Parscale, who quickly parlayed his advice into a role as the campaign’s digital director. By the time Trump won, Parscale was practically part of the family. His relationship with the president “is very close,” according to Eric Trump. “There is a tremendous trust with all of us…He is one of a very select group of people.” (According to the New York Times, Eric’s wife, Lara, has been paid by a Parscale company as a liaison to the campaign, as has Don Jr.’s girlfriend, former Fox News personality Kimberly Guilfoyle.) As Parscale told the Post, “I’m here because I love his family and I wouldn’t have the life I have without him…I am loyal to them.”

“There is a tremendous trust with all of us…He is one of a very select group of people,” says Eric Trump, second from left, of Brad Parscale, lurking at right.

Jeremy Hogan/Sipa/AP

That loyalty may have come naturally. Like Trump, Parscale likes to tell a story of building his business out of nothing. Like Trump, Parscale started with more capital than he likes to admit, and his company boasted of accolades it had never earned. His dad, Dwight Parscale, like the president’s father, is a larger-than-life figure who started multiple companies and employed his son. The elder Parscale’s ventures, like the president’s, were no stranger to bankruptcy and legal trouble.

This upbringing may have prepared Parscale for the central strategy of Trumpworld: Bend, shape, defy, or skirt rules and norms while accruing ever more money and power. It was the theme of Trump’s real estate career—get away with what you can (use accounting gimmicks, create tax shelters) and change the rules when you can’t (lobby Congress for profitable tax deductions). And it became part of Trump’s 2016 strategy (buy the silence of porn stars, sit on tax returns).

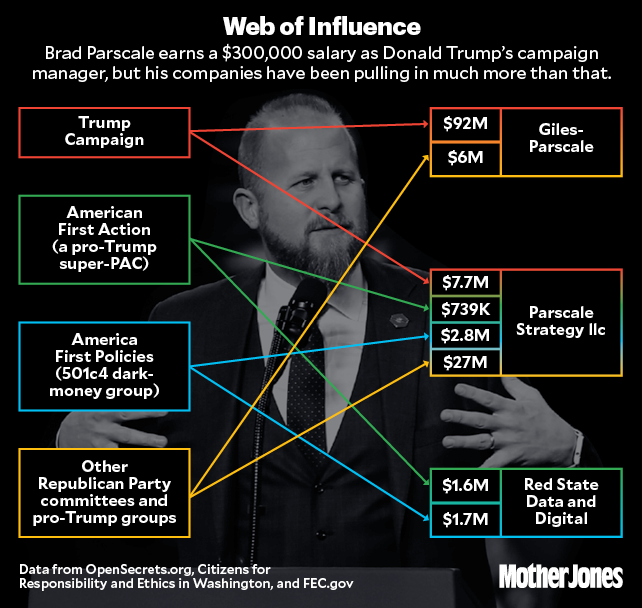

Parscale brought the same ethos to the campaign’s digital strategy. Within a campaign structure flat enough that an outsider with expertise in digital marketing could make key decisions, he pushed the campaign to place a big and successful bet on Facebook—and to route much of the spending via his own company. When special counsel Robert Mueller’s team questioned former Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski in 2017, the FBI agents noted his dismay at Parscale’s decision to “enrich” himself and “put $94 million of campaign money through his business,” according to documents released to BuzzFeed News and CNN.

After 2016, journalists scrambled to explain Trump’s upset win. Never one to miss an opportunity, Parscale harnessed the attention by buying ads directing people searching for him on Google to a new website advertising his services, according to the New Yorker.

Like Trump himself, who is notorious for running his finances through a maze of closely controlled entities, Parscale and companies he is associated with have created a web of businesses and arrangements that obscure their machinations and money flows. As the president’s inner circle prepared to take office, Politico reported that Kushner blessed Parscale’s bid to lead a dark-money organization, America First Policies, to support the new administration. In April 2017, AFP created an affiliated super-PAC, America First Action. According to still-pending federal complaints filed by Common Cause, both groups’ work is illegal because they appear to have been founded in coordination with the Trump campaign, something Parscale essentially admitted when he told the Washington Post that he’d set them up “as an unofficial agent for the Trump family.”

Days after Trump’s inauguration, Parscale also registered a new firm, Parscale Strategy LLC. That August, he split with Jill Giles, the co-owner of his old San Antonio firm. Parscale sold his half, now branded Parscale Digital, to a penny-stock company called CloudCommerce for a nominal $10 million, a transaction carried out largely in virtually worthless shares. Parscale became one of CloudCommerce’s four governing directors. Giles, who declined a request to comment and has insinuated publicly that she didn’t want to work for Trump, turned her half into a new digital design firm also under the quickly expanding CloudCommerce umbrella. Next, Parscale and CloudCommerce purchased a company called Data Propria that had been formed by former employees of Cambridge Analytica—the infamous firm co-founded by onetime senior Trump adviser Steve Bannon, and hired by his 2016 campaign, that had gone bankrupt after the Guardian and New York Times revealed it had a massive trove of shadily acquired Facebook user data. Matt Oczkowski, Cambridge Analytica’s former head of product, became president of Data Propria, which shares a San Antonio address and telephone system with both Parscale Digital and Giles’ firm. While Oczkowski has denied that Data Propria was created to help the Trump campaign, in 2018, AP reporters overheard him woo clients by boasting that he and Parscale were “doing the president’s work for 2020.” The corporate maneuvers raise the possibility that the controversial data could be used in Trump’s reelection; when members of Congress wrote Oczkowski to confirm he no longer had it, he never responded.

In January 2019, Oczkowski took over as head of Parscale Digital on what the company said was a temporary basis. “Matt will continue to lead the Data Propria team and will now focus on streamlining the offerings and building out the teams between the two brands,” CloudCommerce president Andrew Van Noy told employees in an email obtained by Texas Public Radio. (Before joining CloudCommerce, Van Noy filed for bankruptcy, during which time he was sued for fraud, agreeing to pay a large settlement. His predecessor pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit securities fraud.)

My examination of public records shows that since 2017 the campaign, the RNC, and the pro-Trump America First Action PAC have poured about $35 million into Parscale Strategy. It’s unclear how much of that money goes to Parscale Digital and Data Propria back in San Antonio. But in Securities and Exchange Commission filings, CloudCommerce said Parscale Strategy was Parscale Digital’s “largest customer,” bringing in more than $2.5 million in just the first nine months of 2018.

In December 2019, Parscale quietly resigned from CloudCommerce’s board even as he retained a large portion of its shares. For months, financial experts, including a former banking regulator and a business columnist at the San Antonio Express-News, had wondered about the wisdom of his decision to go into business with the company, given its leadership’s past troubles. “You combine a track record of bankruptcies on the part of one principal with a criminal guilty plea of securities fraud—those are as bright a set of warning signs as you can find,” says Jacob Frenkel, a former senior SEC lawyer who now leads the securities enforcement practice at Dickinson Wright. Did Parscale’s new partners hope that his newfound fame and association with the president would drive up share prices, only to discover that his name wasn’t worth as much as they had hoped? Parscale’s deal with the firm, according to SEC records, guaranteed him 5 percent of any revenue generated for the company by Parscale Digital and established benchmarks that could see him earn $1.3 million. If the Trump campaign hired Parscale Strategy, which in turn hired Parscale Digital, Parscale personally would get a cut. But it’s not clear whether the money ever materialized, and CloudCommerce now appears to be broke. A series of small loans documented in public filings suggest it has struggled to make payroll. In March, Facebook ads promoting investment in the company were taken down for violating the platform’s prohibition on “tactics that mislead people through exaggerated promises of guaranteed financial success.”

Meanwhile, Parscale decamped to Florida in 2018, purchasing real estate in Fort Lauderdale, an hour south of Mar-a-Lago. The Daily Mail dug through property records showing that Parscale and his wife, Candice, spent millions on two condos and a waterside home, with expensive cars to go with. “The president is an excellent businessman,” Parscale told the Mail, “and being associated with him for years has been extremely beneficial to my family.” In August, CNN discovered that Parscale was the owner of Red State Data and Digital, a vendor registered in Delaware under Candice’s name that has received $1.7 million from America First Policies since 2017. While Parscale has said he does not take fees from the Trump campaign’s ad buys since he runs the campaign, he has taken fees on millions in ad buys for the RNC.

Parscale’s reputation no doubt benefited from the campaign’s clever use of Facebook ads. But the campaign also gained by bending Facebook to Parscale’s will. An early example came in May 2016, after ex-Facebook employees told Gizmodo that co-workers had suppressed right-leaning content in the site’s trending topics section. A conservative chorus accused the company of discrimination until CEO Mark Zuckerberg and his deputy, Sheryl Sandberg, agreed to meet with a group that included an emissary from the Trump campaign. Facebook denied giving any preferential treatment and conducted an audit to prove it. But three months after the debacle, Facebook fired the contractors who vetted news promoted by the platform, replacing them with algorithms. According to a BuzzFeed News analysis, clicks and shares of fake news stories—most of which favored Trump—soon tripled. The campaign had accused Facebook of bias, and gotten just what it wanted.

With that, the pattern of working the refs was established. When Facebook dispatched a representative, James Barnes, to help Trump’s campaign staff maximize their ad targeting tools, Parscale savvily tapped his expertise. Yet he sometimes treated Barnes as more of a hostage than an adviser. When the campaign wanted to pay for ads using a credit card even though Facebook wasn’t equipped to process daily payments of several hundred thousand dollars, Parscale texted Barnes, threatening that if the demand wasn’t quickly met, Trump would “say Facebook was being unfair” on television, Barnes recently told the Wall Street Journal. Facebook found a fix.

From his perch leading Trump’s reelection effort, Parscale has continued and helped drive a larger full-court press by conservative media outlets and lawmakers pushing Facebook and other tech platforms to behave the way they want. In March 2018, shortly after his appointment as campaign chair, Parscale tweeted a warning: “Hey @facebook @Twitter @Google we are watching,” followed by the staring eyes emoji. “This is your opportunity to make sure the playing field is level.” The tweet preceded a barrage of attacks from the president, his campaign, and GOP officials alleging anticonservative bias in Silicon Valley. As Zuckerberg made his debut testimony on Capitol Hill to address the Cambridge Analytica revelations, congressional Republicans used the opportunity to attack his company’s treatment of the pro-Trump internet duo Diamond and Silk, who had recently accused Facebook of silencing them. The campaign and the party kept up the drumbeat. “We won’t tolerate bias toward conservatives or @realDonaldTrump supporters,” Parscale tweeted in May 2018, attaching a letter he and the RNC chair, Ronna McDaniel, had sent to Facebook and Twitter alleging discrimination against the two sisters. He used the hashtag #StopTheBias.

Eric Wilson, who served as digital director on Marco Rubio’s 2016 campaign, agrees with Parscale that the tech platforms can tilt against Republicans, and that all “conservatives are left to do is work the refs,” he says, to “make sure that they hear our perspective about it. And that’s just smart politics.” Alan Rosenblatt, a left-leaning digital communications strategist, says such claims fit neatly with decades of right-wing claims of media bias: “Being able to attack on anecdotal evidence—whenever something happens, when they take it out of context—is great with the base. It feeds this whole ‘You can’t trust any of the sources of information that are out there. You can only trust information coming from Trump and his campaign.’” The tactic further benefits the right, Rosenblatt says, by rallying the conservative base.

Cable news has been cutting away from @realDonaldTrump’s coronavirus briefings & threatening not to air them at all.

Over 300K people have signed a petition demanding that the #FakeNews keep people informed by carrying the briefings.

Add your name now!https://t.co/vChj9fm546

— Brad Parscale (@parscale) April 2, 2020

By spring 2018, the entire conservative infrastructure mobilized around the idea that a liberal Silicon Valley was trying to muzzle conservatives. In May, when Facebook banned far-right Trump allies including conspiracy theorist Alex Jones, Trump attacked social media companies as biased. “We are monitoring and watching, closely!!” he tweeted. Every decision to remove hate-mongering figures from the platforms was met with similar accusations and, ominously, threats of regulation. Some on the right soon embraced the idea that saying anything you want on Facebook is a civil right.

Unsubstantiated allegations of bias have continued to be a core Parscale tactic. When Facebook briefly blocked White House social media director Dan Scavino from posting comments in March 2019, claiming his repetitive messages had accidentally triggered automated spam filters, Parscale sprang into action. “More tricks from the #PaloAltoMafia,” he tweeted. “I can only wonder how many are blocked that don’t have a voice to fight back,” he wrote, tagging Facebook, Google, and Twitter. He often played these companies off one another: Sometimes he said Google was threatening democracy. Sometimes he put Facebook or Twitter in the crosshairs.

Angelo Carusone, president of the liberal watchdog group Media Matters, said that the Trump campaign was keeping the pressure on the social media giants with an eye toward 2020. “We’re in this period of time right now where platforms will still make changes” to their algorithms and rules, he said last summer, “setting the rules that will determine a lot of the content that we see next year…These platforms will mollify their right-wing critics because they make a lot of noise.” Parscale, Carusone added, gets that.

Sure enough, on September 24, 2019, Facebook made clear that politicians were exempt from its fact-checking efforts, allowing them to spread lies in both paid ads and so-called organic posts. Russia’s propaganda machine had amplified disinformation in 2016; in 2020, American politicians would be free to do it themselves. Like the conservatives exerting constant pressure on him in public and in a series of private dinners orchestrated by the company’s Washington team, Zuckerberg explained the policy as a defense of free speech. Within weeks, the Trump campaign blasted out a video ad that falsely purported to show Joe Biden confessing to bribing Ukrainian officials to benefit his son. The ad was viewed as many as 11.3 million times on Facebook and 12 million times on YouTube, a Google subsidiary.

In November, when Google announced new limits on the ability to microtarget political ads, Parscale fired back. “Funny how @Google wants to act like they want more voter participation, but that is a marketing lie,” he tweeted. “Time for Congressional action to protect Political advertising.” In January, Facebook said that it wouldn’t follow Google’s lead and would continue to allow campaigns to send highly specific and untruthful ads to small groups of users. Meanwhile, Attorney General Bill Barr had initiated antitrust investigations into major social media companies, reportedly including Facebook, providing the administration with another possible point of leverage as the presidential election nears.

So far, the Trump campaign hasn’t made a habit of blatantly false ads. Instead, its messaging has focused on stoking outrage and fear, sometimes laced with lies. Last spring, Trump tweeted a video splicing footage of Rep. Ilhan Omar, one of the first Muslim women to serve in Congress, with images from 9/11, implying she didn’t care about the attack. The tweet sparked death threats against the Minnesota Democrat, forcing the House’s sergeant-at-arms to review her security. But rather than remove it, the campaign kept the outrage going through Facebook, placing more than a hundred ads smearing Omar as anti-Semitic and soft on terrorism. Between January and August 2019, the Trump campaign ran more than 2,000 Facebook ads warning about an “invasion” of immigrants at the southern border. On August 3, a gunman killed 22 people at a Walmart in El Paso after posting a manifesto that noted his politics “predate Trump,” but that echoed language the president had used by saying he was acting in “response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas.”

Facebook has said it will pull down ads that engage in overt voter suppression or incite immediate violence, but this stance overlooks the fact that the kind of caustic digital ads Parscale has wielded can instill fear and radicalization over time. “They’re a private company that’s being forced to react to a president whose rhetoric, frankly, is dangerous,” says Daniel Kreiss, an expert on political communication at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Though Facebook is unwilling to police most political ads, it is happy to profit from their spread. Its algorithms, Kreiss notes, are geared for maximum engagement, with posts that do well getting a discount that helps spread incendiary content to its “most extreme audiences.” Wilson, the GOP consultant, says, “It’s a really bad incentive structure. And that’s the core of Facebook’s business model.”

In 1988, supporters of George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign ran the Willie Horton ad, not-so-subtly evoking racist stereotypes of dangerous Black criminals. Unlike Trump’s microtargeted appeals stoking bigotry, “Everyone saw it,” says Kreiss. “Journalists could talk about it. Rivals could basically engage in counterspeech against it. With television, it was de facto public in a way that digital political advertising is not.” Now, it’s impossible to track exactly who is getting such messages, much less rebut them. “The scale is different,” he says. “You can reach a lot more people.”

If Facebook ever considered attempting to draw bright lines on rhetoric, that time has long passed. The company’s executives have said it wants to be neither the arbiter of truth nor the arbiter of hate. If it were to take up those tasks, Trump could bring the full might of the right, and possibly the federal government, down on them. Meanwhile, his campaign’s posts include a steady drumbeat of inflammatory messages, playing on fears of immigrants and Muslims, of “fake news media” censorship, and of violent “radical left” antifa “mobs.” And so the stage for 2020 is largely set.

In January, Parscale traveled to New York City to appear on the debut episode of Fox News’ Bill Hemmer Reports. “I flew all the way here just to see you today and help you,” he told Hemmer, perhaps expecting the mutual exchange of flattery that Parscale regularly receives on the network. Instead, Hemmer cited a poll showing Trump’s approval “down by a whopping 24 points” with suburban women. Parscale insisted the figures weren’t accurate, pressing a message that he’s since touted on multiple Fox News shows. “He is so far ahead of where he was in 2016 against Clinton,” Parscale declared. “We’re going to have the ground game ready. We’re going to have the digital game ready. We’re going to be ready.”

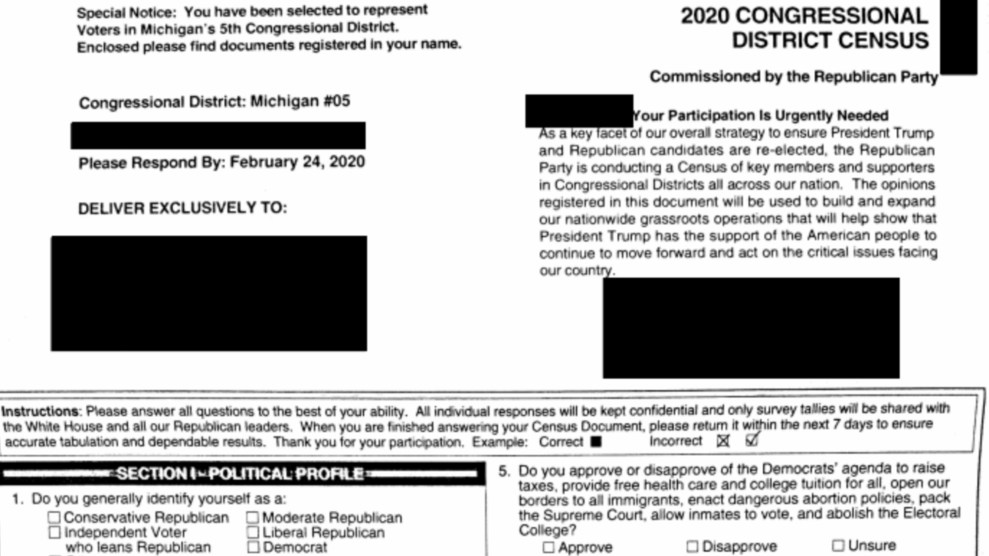

As evidence of the Trump campaign’s momentum, Parscale trots out big numbers. It’s raised over $200 million and already spent $40 million on Facebook and Google. These digital ads largely target the president’s existing supporters, selling MAGA hats, pushing surveys, and soliciting petition signatures—ploys to boost engagement while raking in contact information and donations. Those personal details are passed on to the Data Trust, a massive centralized clearinghouse that works exclusively with the RNC. There, information about who and where voters are, what they respond to, and how to reach them is merged with commercial data on consumer habits, opinions, and predilections. “The campaign is all about data collection,” Parscale told the Guardian in January. “If we touch you digitally, we want to know who you are and how you think and get you into our databases so that we can model off it and relearn and understand what’s happening.”

The @TeamTrump online campaign is 🔥🔥🔥!

Since going all-virtual March 13:

❗️276K NEW volunteers

❗️13,347,694 volunteer calls to voters

❗️All Trump Online programs top 1 MILLION viewers EACHHuge numbers Sleepy Joe can’t touch.

People MOTIVATED to re-elect @realDonaldTrump!

— Brad Parscale (@parscale) April 8, 2020

Parscale likes to say that Trump won in 2016 with a motley digital team that had just a few months to fundraise and run online ads. The threat it poses to Democrats in 2020 is more formidable: It has had three years to fundraise, build digital operations, and recruit supporters. But some people familiar with the internal workings of the Republican Party believe the myth of Parscale’s success may put the story backward, that the team wasn’t so ragtag after all and Parscale may not be suited to build it further. His Trumpian tendencies, boastfulness, and confidence may have gotten him where he is today—but they might not serve him well as campaign chief.

Take Caldwell, who, given her own history with the party, can’t get over the coincidence of having landed at a Iowa caucus site alongside Parscale. “It was crazy that Brad and I wound up at the same location,” she told me, where she listened to him reassure Trump supporters that data showed the campaign was assembling a broad and diverse coalition. Until she joined Walsh’s now-mothballed anti-Trump campaign, she’d worked for Crowdskout, a software platform that analyzed digital engagement for the RNC in 2016 and 2018. “I’ve spent countless hours poring over data about Republicans,” she said, recounting what she told voters after hearing Parscale’s spiel, “and I can tell you we are losing women, we are losing people of color, we are losing people in the suburbs. So he is not telling you the truth.”

Parscale had already left the caucus site when Caldwell delivered her critique. But his claim suggests he knows those groups could be Trump’s Achilles’ heel in November. They are the moderates turned off by Trump’s behavior as well as the key voters of color whose turnout will help determine whether knife-edge swing states again tip to Trump. With a pandemic raging, influencing those voters’ through online persuasion will be critical for the 2020 contest, the outcome of which will shape history’s verdict on Parscale, and whether he earned his job thanks to the magical abilities of a master digital marketer or whether he merely lucked out in 2016.

According to Caldwell, party staffers “really should get more of the credit for that victory than they do.” While Cambridge Analytica was peddling “snake oil” about psychologically manipulating voters, she says the Republican National Committee was gathering and using data the old-fashioned way. “The best way to know how people are going to vote or how they feel about something is to ask,” Caldwell said. “That’s what the RNC field team was doing really, really effectively in 2016.” The party had also invested in data infrastructure to counter the sophisticated analytics that aided President Barack Obama’s reelection, setting up systems ready to spring into action for whomever became the nominee. It wasn’t Cambridge Analytica but three data firms hired by the party to work alongside its own formidable analysts, who, according to AdAge, were responsible for squeezing out Trump’s Electoral College win. As Parscale himself admitted a month after the election, “The RNC had built a data and voter contact program that was really plug-and-play ready for the next candidate.”

But the RNC of 2016 is not the RNC of 2020. By 2018, “there were not a lot of thinking people,” Caldwell says, “but the thinking people had built a lot of good infrastructure that, by just sticking with the plan, the dummies in the room could manage.” In place of the departed data brain trust came former RNC Chief of Staff Katie Walsh, who the New York Times has reported shared a Trump Tower office with Parscale in 2016, but who had less data experience. The new chief data officer was Ellen Bredenkoetter, who according to Caldwell and another source, was chosen by Walsh’s husband, Mike Shields—another former chief of staff for the party. (RNC press secretary Mandi Merritt denies Shields was involved in Bredenkoetter’s hiring, and says she was “clearly the best person for the job.”) Like Parscale, Walsh and Shields are connected to businesses that have seen major paydays from Republican committees and related groups in the wake of 2016—nearly $13 million as of last October, according to the Washington Post. Parscale’s take hasn’t gone unnoticed; according to the Times, the president has sent word that he should restrain himself from making more than $800,000 on the 2020 campaign.

Parscale watches his boss at a rally in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Andrew Harnik/AP

“Clearly, all decisions made by the RNC are in the best interest of the Trump campaign and electing Republican candidates up and down the ballot,” says Merritt. But in addition to making the committee an organ of Trump’s reelection bid, Walsh, Shields, and Parscale have also forged a powerful alliance to dole out contracts across the country. “You have Parscale actually making phone calls into campaigns, strong-arming people into hiring Mike Shields, which is something I’ve never seen before,” said a person who has done data work for Republican campaigns. “That becomes a real problem when they’re out consulting for candidates in primaries and making decisions about how money is spent.” Such worries are echoed by other party insiders even if they won’t speak as publicly as Caldwell—that the party let go of its best minds in place of people, including Parscale, who profit by exerting control over the party and its data operation at the expense of Republican candidates and even the president.

As another Republican data wrangler told me, if the reelection campaign was using its enormous databases effectively, its digital ads, emails, and even text communications would appear more personal and engage more demographics by making a case for the president. Perhaps Parscale has a grand plan to do that, to start wooing suburban voters and mitigate Trump’s margins with people of color. On TV, the campaign has run a spot that debuted during the Super Bowl highlighting Trump’s 2018 commutation of a Black woman’s sentence for a nonviolent drug offense on Bravo and Lifetime, networks with large female audiences. But the Trump campaign’s digital presence notably lacks positive messaging, something that insiders say indicates Parscale’s lack of ability to do much besides express Trump’s enraged id. The coronavirus presents an added challenge to any effort to boast of presidential successes. “Inevitably, the Trump campaign will seek to turn this into an argument for reelection—either because they can’t resist, need to salvage his declining approval ratings, or both,” says Daniel Scarvalone, a data strategist who worked on Obama’s 2012 campaign.

While the Trump campaign’s communications department is already turning out daily messaging memos to reporters that praise Trump’s handling of the crisis and trash former Vice President Joe Biden for a role in the Obama administration’s purported failure to adequately stockpile medical equipment and protective gear, its digital operation has yet to follow suit. Some Democratic analysts say they suspect such reticence is due to a fear of taking blowback for immediately politicizing the pandemic, but the coronavirus crisis looms so large that digital ads on it seem inevitable.

In the meantime, Scarvalone says what Trump’s digital operation is “designed to do is not what Brad Parscale tells a lot of people…It’s designed to make people angry. It’s designed to get people who are already strong supporters of the president to give information to the campaign about them. And it’s designed to get strong supporters of the president to do stuff—whether that’s giving money, it’s buying merch, it’s buying red hats.”

While that effort may be working, Scarvalone says “a smart campaign will figure out how to walk and chew gum at the same time, because every campaign needs to raise money and get volunteers but also needs to talk to voters and lay out a vision for the country and lay out why they’re better than the other guys. And I see them doing the first really well, but they’re not doing the second online.”If the campaign was already slow to use its digital and data operation to reach voters with a case boosting Trump, the pandemic presents yet another hurdle: how to create a positive message around a fast-evolving and increasingly deadly crisis.

But then, Parscale doesn’t like playing by the rules, and he’s gotten rich by helping the internet devolve from its starry-eyed vision of a communitarian future into a cesspool of misinformation and fearmongering. Trump’s appeal has always been more about the way he assaults norms than cleverly pushes their limits. In Parscale, Trump may not have hired the best person, but he hired the one most like himself.