Pat Timmons-Goodson.Pat Timmons-Goodson for Congress.

Like Merrick Garland, who then-president Barack Obama nominated to serve on the Supreme Court, Pat Timmons-Goodson was the perfect appointee for the judicial position she did not receive. Her familiarity with North Carolina’s courts went back to 1981 when she began her three-decade legal career as an assistant district attorney in Cumberland County, home to Fort Bragg and Pope Field. Before being nominated in 2016 to be a district judge on the US District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, Timmons-Goodson was a justice on the state’s supreme court and vice chair of the US Commission on Civil Rights.

As with the US Supreme Court, federal judges must be confirmed by Congress, which Republicans controlled at the time of the nomination. And, as with their approach to the nomination of Merrick Garland, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky) wasn’t about to play a part in broadening Democratic control of the courts by conducting confirmation hearings for the nominees. So she waited out the final year of the Obama presidency in purgatory, until Donald Trump’s inauguration, when her nomination expired.

Now, Timmons-Goodson hopes to move from the judicial to the legislative branch of government by running for North Carolina’s 8th congressional district this November. She hopes to dislodge Richard Hudson (R-NC), a moderate Republican who’s comfortably held the seat since his victory in 2012. In the years leading up to Hudson’s tenure, the seat was held be two officials dogged by scandal. Democrat Larry Kissell, who won the seat in 2008 with the support of labor unions, lost their backing when he voted against a healthcare reform bill in 2010—ultimately causing them to run an independent candidate against him. More recently, Robin Hayes, a Republican who held the seat before Kissell, resigned as head of the state’s Republican party after a corruption indictment in April 2019.

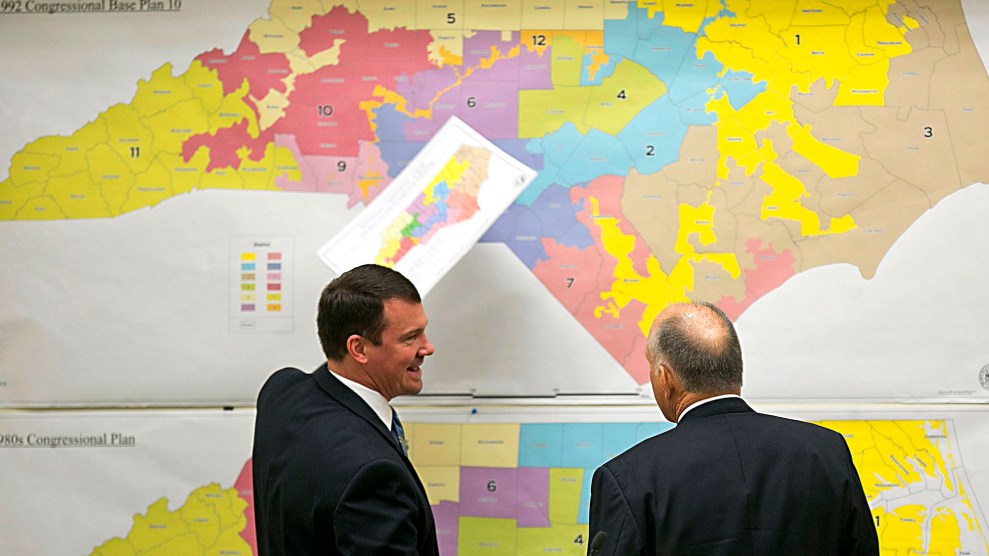

In September 2019 the district changed when a panel of three judges ruled that partisan gerrymandering had to stop, and the congressional map was redrawn. The result was that the less conservative Cumberland County—where Timmons-Goodson spent much of her childhood and cut her teeth as a young attorney after graduating from the University of North Carolina School of Law—was folded into the newly created district.

Timmons-Goodson announced her candidacy in December, but three months later the novel coronavirus epidemic made traditional campaigning impossible. Mother Jones caught up with her to talk about her shift into politics, how to campaign when there’s an epidemic, and how COVID-19 has made the issues already facing the 8th district more visible than ever. As she wrote in a recent op-ed in the Fayetteville Observer, “I reminded my mother that many have said, ‘When America catches a cold, African Americans catch pneumonia.’ COVID-19 has shown that saying still holds true.”

How has this pandemic altered the day-to-day operations of your campaign?

The manner in which we go about campaigning has changed, but the goal hasn’t. The goal has always been and will continue to be communicating with our voters and our supporters, and listening to what’s on their mind, and for us to communicate what our priorities are and how we would plan to serve them in Washington. Back in the good old days, you would go out to an event and physically be present in the same room with someone, where you can slap your supporter or friend on the back, shake their hand, kiss their baby. We’re unable to do that. But the goal is the same. So we’re now on the telephone, or we’re on Zoom. I’ve tried to set up a location that, when I’m there, my mind is in the work mode, but still haven’t quite achieved that yet. Maybe the dining room today if the Zoom meeting is a little more formal. If I’m just talking and working with staff, I may be in the guest room in a real comfortable chair with my my feet up.

In your op-ed you write about how Black and brown lives are disproportionately affected by this pandemic. With Black people comprising nearly a quarter of the population in your district, how has this crisis played out locally?

I hear that parents who [usually] work outside of the home and are no longer working have their children at home, and they understand just how huge a role the school day has played, not only in the lives of children by educating them, but also supervising and feeding them. They’re seeing how that food bill increases mightily with the children being home. We are seeing more food shortages, and we see more folks calling for help.

I’m sad to say that I’ve had a number of friends lose their spouses. A few of the losses have been directly related to the virus, but the virus has affected the way that everyone is able to grieve and say goodbye to their loved ones. For example, two of my friends have lost husbands, and they were military veterans. They’re not having the kind of funeral services that they would have had. So they’re delaying the memorial service or a goodbye that would be more in keeping with the way families grieve. At Fort Bragg, if the person is going to be buried at the cemetery, the family can’t come. The military honors that wouldn’t normally go with the funeral are not taking place. I’m hearing that the virus is affecting us in ways that we never would have imagined at all. All of the ways are heart-wrenching.

How would you describe the 8th District and the region around it to someone who’s never been there before?

In my mind, it’s so like the south. There is a warmth there. There is a “wholiness,” if there is such a word. There is a reliance on relationships and on people and on families. In this part of North Carolina and in this part of the country, you don’t have to be related by blood to be considered family and to be treated as family.

It’s mostly suburban, demographically diverse, made up mostly of military and working middle-class communities. Many of those communities have been hit hard by the closing of textile mills. At one time, Cabarrus County was the home of Cannon Mills, which was the largest producer of textiles in the world, before manufacturing went out of the country. Working middle class communities trying to support their families.

I know you were a child in this part of North Carolina. How has the area changed?

In the eastern part there’s Fort Bragg, and Pope Air Force Base, so you have a strong military presence that plays a large role in the economy. As you move further west, you get into counties and areas that are not as heavily populated. Small towns, small communities that, like other places in this nation, have really taken a hit. Much of the manufacturing is long gone, and it’s not going to return unless there is a real concerted effort to bring it back. We’ve got to find a way to have some kind of economic engine to support them or else they literally are going to wither up and die. As I’ve looked at the discussions about the shortages of certain garments and personal protective equipment, I was like, “Daggonit, that could have been manufactured right here in our district.”

What are the biggest policy changes that are needed here right now?

I’m going to lead with healthcare, because I was talking about health care before the pandemic. And that’s at the heart of everything. You can’t work very well, you can’t get an education, you can’t function if your health is impaired or if you’re not healthy. This country is just too rich for folks to be denied something so basic. For me, it’s just unconscionable that we would have citizens that do not have proper healthcare.

I’m the product of a military family. My father was a sergeant in the United States Army. That’s how it is that we came to settle in Fayetteville. Dad medically retired from the army. I’d been getting government healthcare the whole time I was raised, because that’s what was provided for our military servicemen and women. And it worked, so that’s where I began my frame of reference.

At what point did you become politically conscious?

I would say fairly early on. I’m the oldest of six. I was always around adults and always given a good bit of responsibility. My ears would always pick up when grown people were talking. I would hear family members and friends talking about having a situation where they were unsure just what to do. And eventually somebody would say, “You need to talk to a lawyer.”

I got in my young head that that’s the folks who can get things done. I wanted to be like that. I’ve grown to understand that there are a lot of professions that help people, but I identified the legal profession early on, as a preteen. And in the mid-60s, when I saw what was going on, I thought, that I wanted to be a part of it.

You have had a long, illustrious career in civic service. Having spent that career in North Carolina, I wonder if you’ve ever worked with Reverend William Barber, and what that was like?

My path did not cross with him until I was in the judiciary of North Carolina on the Court of Appeals. North Carolina elects all of their judges. That’s when I met Reverend Barber. And as our campaign went around the state, I worshipped at his church. I was involved with the NAACP, attending meetings, and he was the president at that time, of the state NAACP, so I’ve interacted with him over the years. For me, he represents an individual that, while working as hard as humanly possible for a cause and a people—the poor, the disenfranchised, the vulnerable—he’s still managed to keep his focus on the individual. So it’s about helping the masses, but at the same time it’s about the individual. He’s an incredible human being.

You’ve worked on the US Commission on Civil Rights since since 2014. Why would you shift from that form of advocacy work to running for office?

I realized shortly after joining the commission that it didn’t matter how great the policy was, or how much the change was needed. It didn’t matter how many people would be favorably impacted by a particular policy. Unless you had a legislator that would file the legislation, nurture it, move it along, it did not happen. That’s when I realized that I needed to do more. Our citizens can only select their leaders from those that offer themselves, so I said, “Well. I’ll offer myself and we’ll see what they say.”

What’s a past experience, perhaps an unexpected one, that’s helped prepare you to run for this office?

I think that it would be seeking a judicial appointment that I did not receive. I received a call afterwards from a judge who I really admired, and he said, “Pat, I understand you didn’t get that appointment. I hope that you will not stop. Just because things don’t come when we want them or the way that we want them does not mean that they will not come. This time can be used by you to even better prepare yourself for further service. And so you just hang in there.” I have always appreciated that. You just keep on working at it, and things will work out.

The district lines were redrawn in a way that has brought some benefit to the Democrats. But it still leans Republican. What are the greatest challenges here to winning?

The greatest challenge to winning will be having the means of communicating who I am and my message. I believe that the people of this district want something to be done, and that something may vary depending upon who is answering the question. But I believe that they are sick and tired—Republicans and Democrats—of the gridlock that is in Washington. Doggone it, do something! You can’t do something if you are so deeply entrenched in your thinking that you’re unwilling to listen to the other side. The status quo is not going to change unless there is some meeting of the minds, some willingness to give up a little something in order to get something.

I am still very much a judge in terms of my personality and my way of thinking. I look at both sides of the issue, I can’t help it. But I’m gonna listen to what you have to say, and I hope you’ll listen to what I have to say. If you will truly listen, if I will truly listen, I believe that we’ll be able to find some common ground somewhere so that we will move away from the status quo.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.