A young mother speaks on the phone from a family detention center in Texas in 2016.Ilana Panich-Linsman for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Last week, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents at family detention centers presented parents with a horrifying question, according to four attorneys with clients at the facilities: Would you rather stay detained together or be separated from your children? In the second scenario, kids would be released from ICE custody while their parents remained locked up in unsafe conditions during a pandemic.

Lawyers with the legal-aid groups RAICES, ALDEA, and Proyecto Dilley say ICE effectively ambushed their clients and blocked parents from consulting attorneys before answering that question. In some cases, parents were asked if they would want to put their children up for adoption or send them to foster homes, said Andrea Meza, RAICES’s director of family detention services. “Our clients were appalled that this would even be a question posed to them,” Meza added. “One client stated that he and his family expected more coming to the United States and seeking protection.”

ICE officers went to the three family detention facilities in Texas and Pennsylvania a day before the agency had to submit reports in two lawsuits seeking to force the release of detained families. On April 24, a federal judge ordered ICE to “make every effort to promptly and safely” release children from its detention facilities. ICE is not supposed to detain children for more than 20 days because of a longstanding agreement known as the Flores settlement. But that agreement only requires that children be released, not that they be released with their parents. Immigrant advocates have long feared that ICE would take advantage of that by enacting a so-called “binary choice” policy, under which parents would be forced to choose between indefinite detention together or family separation.

ICE is denying that what happened last week was binary choice. The agency explained in a statement Thursday that it does not need to release children whose parents waive their “court-ordered option” to be released to a sponsor. “This court-ordered option has been incorrectly reported as a change in policy,” the statement read. “This is simply false.”

But ICE’s statement misleadingly suggests that the court order boxes it into giving parents a choice between indefinite detention together and family separation. There is nothing in the court order that prevents ICE from releasing families together. The agency also said that last Thursday’s actions were “not new,” but Bridget Cambria, ALDEA’s executive director, told Mother Jones she knows of only one case before last week where ICE asked a parent whether they wanted to remain detained together or be separated. (Another reason to be skeptical of ICE’s denial is that the Trump administration has repeatedly claimed it did not have a family separation policy, maintaining that it had a policy of prosecuting parents for crossing the border without authorization. Prosecuting those parents led to the agency separating thousands of parents from their children.)

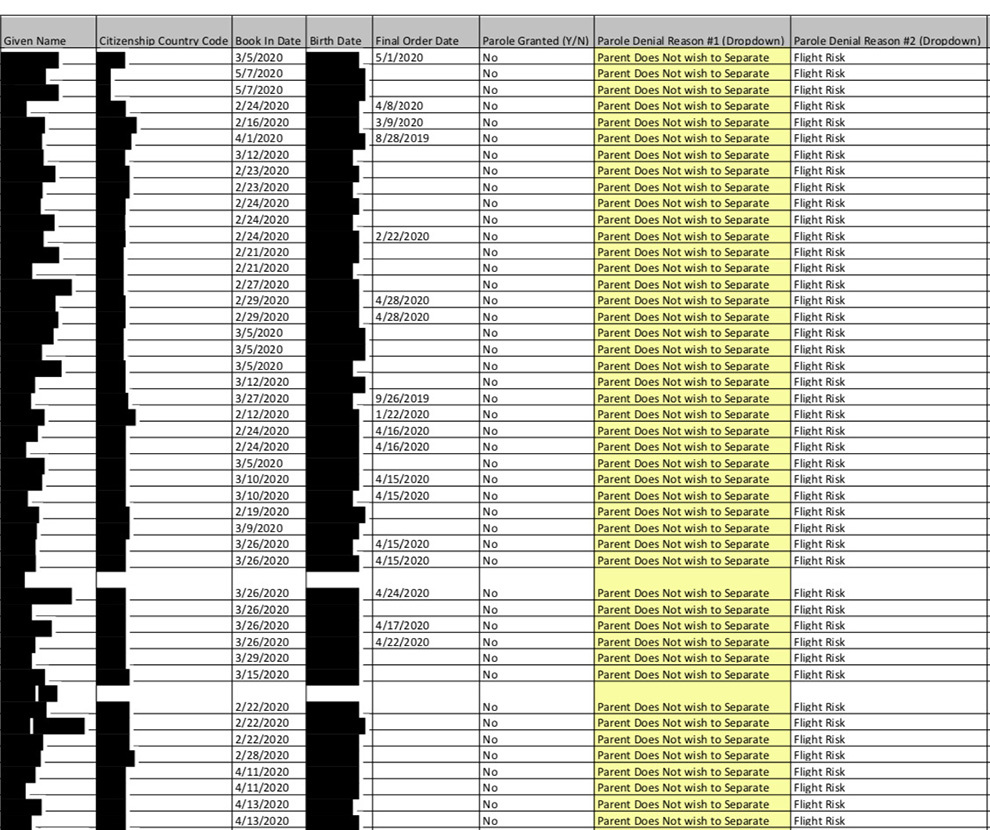

A report submitted by ICE last Friday provides a more accurate picture of the agency’s actions. In the filing, ICE Juvenile Coordinator Deane Dougherty included a spreadsheet that listed reasons why ICE declined to release individual children on parole last week. In many cases, the stated reason was “Parent Does Not wish to Separate.” None of parents approached by ICE last week chose to be separated from their children, according to the attorneys representing the families at all three detention facilities.

Cambria said ICE’s earlier denials were nothing but semantics. Shalyn Fluharty, Proyecto Dilley’s director, said, “What is certain and consistent is that these choices were presented to our clients, and that our clients walked away truly feeling like they were being asked to say goodbye to their children.” Fluharty said some parents at family detention center in Dilley, Texas, were simply asked to raise their hands to indicate whether they wanted to be separated or remain together.

In 2018, the Trump administration tried to get around the Flores agreement by using its “zero tolerance” policy to prosecute parents who came to the United States with their children for crossing the border without authorization. That allowed ICE to separate thousands of parents from their children without a plan for reuniting them. A public backlash forced the Trump administration to abandon its family separation policy days before a federal judge officially blocked it. The lingering nationwide outrage appeared to prevent ICE from replacing it with a binary choice policy.

Children separated from their parents are usually sent to shelters run by the Department of Health and Human Services before potentially being released to live with relatives or other sponsors. If sponsors aren’t available, those children can be sent to foster homes. Parents deported alone could remain permanently separated from their kids.

The report ICE filed in court Friday shows that 185 children were detained at the three family detention centers as of the end of last week. Many of those children had been detained since February. Cambria said families were distraught when describing the chaotic situation at the Berks detention center in Pennsylvania. While some agents spoke Spanish, official interpretation was not provided, including to at least one parent who spoke an indigenous language. Fluharty reported that one of the parents said about the ICE agents, “We felt like they were really enjoying watching us suffer.”

Parents have been afraid for months that the new coronavirus will get into family detention centers. They’ve watched the pandemic unfold on TV, at least until recently, when TVs at some of the facilities were turned off. In late March, a 5-year-old girl at Berks was rushed to a nearby hospital with pneumonia-like symptoms—only to be returned to the facility that same day and put in isolation with her mother after being tested for COVID-19. Her test came back negative, but many of ICE’s adult detention centers are now facing the outbreaks that experts warned would be inevitable if the agency kept refusing to release people.

As of Thursday, 1,181 of the 2,368 adults ICE tested had COVID-19. On May 6, ICE confirmed the first death of a detainee because of COVID-19. Last Sunday, a second man died soon after being released from a detention center that had been hit by the virus. (He had not been tested before leaving ICE detention.) Two guards at a Louisiana detention center also died after testing positive for COVID-19.

Alison Herre, the managing attorney at Proyecto Dilley, described last week’s actions by ICE as “coercion that surpasses reason.” The American Academy of Pediatrics has strongly opposed the detention of children for any length of time. “A choice to be separated from your child is no choice at all,” Meza, of RAICES, said. “We know that separating a child from their parent results in lasting trauma.”

ICE has the power to release families at any time. “Tomorrow, every single family could leave family detention,” Cambria said. “They’re all asylum-seeking families. They’re all parents and children who are here seeking protection and who have suffered the most unimaginable types of violence.”