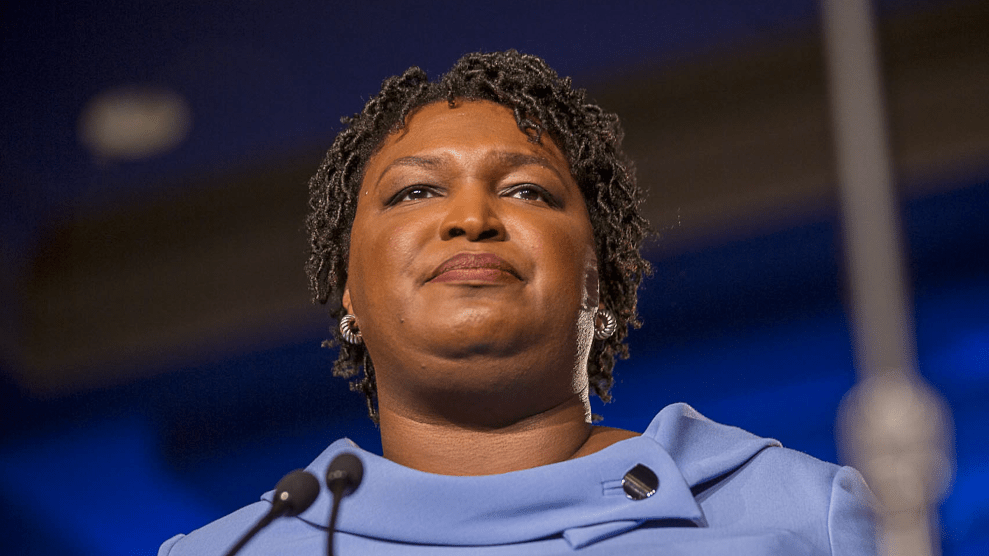

Alyssa Pointer/ZUMA

The president’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, sparked a national panic attack on Tuesday when he suggested to Time that he had personal insight into whether or not the 2020 election would take place, leaving room for some doubt. “It’s not my decision to make, so I’m not sure I can commit one way or the other,” he said about holding the November poll. “But right now, that’s the plan.” The elections are run by the states; the president can’t change when they happen. But Kushner’s quote was worrying enough for those who are already vexed about the executive branch using the coronavirus crisis to further impede the right to vote (or, in the worst-case scenario, cancel elections outright). And the comment was so brazen that Kushner himself experienced a rare jolt of self-awareness: He issued a new statement to NBC on Wednesday conceding, “I have not been involved in, nor am I aware of, any discussions about trying to change the date of the presidential election.”

It may have simply been a piece of Kushner puffery, the latest in a long career of self-regard (recently he described the administration’s coronavirus response as a “great success story”), but the collective freakout points to very real concerns over threats to the 2020 vote, as the president ramps up campaign rhetoric against vote-by-mail, and his party attempts to stymie participation in the states.

Recently, our senior reporter Ari Berman sat down (via Zoom, of course) with Stacey Abrams, the former candidate for governor of Georgia, to rank some of the biggest impediments to voting rights across the country and discuss how the pandemic is being weaponized against participation, especially among voters of color. In a wide-ranging chat, which you can hear on this week’s episode of the Mother Jones Podcast, Abrams talks about launching her voting rights initiative, Fair Fight, after her narrow 2018 loss to now-Gov. Brian Kemp; ongoing threats to the 2020 census; Kemp’s response to COVID-19; and the dangerous attempt to suppress voters during the Wisconsin primary in April. “That was a tragedy and a travesty that should not be repeated in a democratized, industrialized nation,” Abrams tells Berman. “We were able to vote during the Civil War, we were able to vote during the Spanish flu of 1918, there is no excuse for not holding our elections in 2020.”

You can listen to the full show, read an edited transcript, or watch the full livestream of this discussion below.

Stacey, thank you so much for joining me. How are you doing?

I’m doing well, thank you. I’m ensconced in my dining room in Atlanta, Georgia, and doing my best to socially distance and stay sheltering in place until it truly is safe to go back out.

How prepared do you think the US is right now to hold a presidential election in a pandemic?

The United States has the capacity to hold an election in a pandemic. What we lack is the will and the investment. South Korea, on April 15, held their national election. They held the single highest turnout election since the 1990s, and they did it safely. Every state in America has the capacity for vote-by-mail. Every state has the ability for in-person early voting and in-person voting on the day of the election. We simply have to make it safer. But any argument that we don’t have the capacity is wrong. We were able to vote during the Civil War. We were able to vote during the 1918 Spanish flu. There is no excuse for not holding our elections in 2020.

How prepared do you think states like Georgia are to vote by mail? Only 6 percent of Georgians, for example, voted by mail in 2018.

While only 6 percent may have used it, we saw a dramatic increase. In fact, we saw the largest increase among African Americans. My campaign in 2018 sent out 1.6 million vote-by-mail applications. We followed it up with encouragement, but also education.

There’s been a lack of trust in vote-by-mail, particularly from communities of color, because most the rejection rate for communities of color is much higher than for the white communities. In Georgia, we had a specific incident with the current governor, then Secretary of State, who arrested and jailed 12 people for using absentee ballots properly. They lost their jobs. They lost their reputations. And not a single person was convicted. But that created a dampening effect on the use of absentee ballots.

I wanted to ask you about Wisconsin. Republicans refused to postpone [the 2020 primaries]. They refused to mail ballots to every registered voter, and thousands of people were forced to choose between their health and their ballot. When you saw all that, when you saw the long lines of voters wearing masks, what was your takeaway?

We knew there was going to be something catastrophic that would happen in 2020 to elections. I had no idea it would be a pandemic, but we knew that it would happen. Voter suppression is systemic. It’s built into the process. What we have to learn from Wisconsin is that we have the capacity to still make it work if we start early enough. What happened in Wisconsin was that the decisions were made in a matter of weeks. We now have months to prepare. But we have to remember that for those thousands of people who stood in line, for those who had masks or didn’t, and for the poll workers who didn’t have adequate equipment, 52 people have already been confirmed with COVID-19. That should not happen.

There are already people who don’t have the IDs required to vote, who’ve been purged from the voting rolls, or who’ve been forced to wait in long lines or whose polling places have been closed. How concerned are you that the coronavirus is going to add an additional layer of voter suppression?

What COVID-19 has done is reveal what has been a systemic challenge for most of the 21st century. But now that more people are seeing how the systems actually work, they’re understanding. The reality is those things existed in 2019, 2016, 2012, 2008. The difference is, because of COVID-19, people are seeing it in real time and they’re understanding its impact.

I do not welcome a pandemic, but I think what has happened is that people see what’s what’s going on. Luckily, there has been bipartisan support of vote-by-mail, of safer voting, of better instruction. That bipartisanship has to win out because we cannot allow a conservative minority of thought to limit access to democracy and one of the most pivotal elections in our lifetimes.

I want to ask you about Georgia. When you see Brian Kemp rushing to reopen the state, when you see him say that he didn’t know that coronavirus cases could be asymptomatic, do you just think, I should’ve had this job instead?

I think that the voters of Georgia were robbed of their opportunity to make an informed decision. I believe that voter suppression stole the voices of thousands of Georgians. If I were the governor, I would have followed the facts and the science. I would have known early that asymptomatic people can carry the disease. I wouldn’t have led Georgia to be one of the last states to shut down, and we certainly wouldn’t have been one of the first to reopen. Since the reopening of the state, we’ve seen our COVID rate skyrocket by 40 percent. We still are one of the slowest in testing. There is a contact tracing program that’s getting up and running, but it’s woefully behind where it should be. And so, yes, this is a perfect example of why I believe voting matters and having the right to choose your leaders matters. People may have decided not to pick me anyway, but because of voter suppression, we will never know what the choice of the people would have been.

You mentioned voter suppression in Georgia, where there were 214 polling places closed, 53,000 voter registrations put on hold before the election—80 percent from voters of color—and 1.5 million people purged from the rolls. There were four-hour lines in black neighborhoods. How concerned are you that in 2020 there could be a situation like in Georgia where there’s a very close disputed election that go to the Supreme Court?

I believe that what we saw happen in Wisconsin legitimates any degree of concern about how the Supreme Court is going to handle questions of elections. If you look at what happened in North Dakota in 2016, when they refused to enjoin the disenfranchisement of thousands of Native Americans who could not possibly meet the standards. What we saw happen with Wisconsin, that has created a through-line of deep concern. And let’s not forget what happened in 2000. We know that the Supreme Court has not proven themselves to be good actors in this.

The 2020 census has also been derailed by the coronavirus. What do we need to do to get the census back on track?

I am deeply concerned about the census. The Census Bureau has done as much as it can. But we’ve got some major challenges. We know that in rural communities, 6.2 million people have not received the hand-delivered census packets that they need. That includes most of our Native American families. We know that they’ve delayed the counting of nontraditional folks, meaning those who are homeless, those who are living on college campuses, who are living in nursing homes. Those counts have been delayed until June. There might be thousands of college students who go uncounted. And the last major concern I have is that, because we don’t have folks in the field knocking on doors, getting the response rates up, the Census Bureau is going to use a statistical process called “imputation.” That means that they’re going to look at neighborhoods where people didn’t respond, and based on the demographic data of that neighborhood, they’re going to impute who else lives there. Which means minority communities that are already undercounted risk being statistically erased from the narrative of America because we don’t have the ability to go out and knock.

Another big issue right now is what’s happening to the postal service. I’m sure you saw the Washington Post article that said Trump is going to name the chief fundraiser for the Republican convention to be postmaster general. What’s your concern about what’s happened to the post office?

The post office is a vital utility in our nation for many communities, especially rural communities. It is their pharmacy. It’s the only way they get their medication. In the moment of COVID-19, it’s the way people get their food. This attempt to not only privatize but politicize the post office is very dangerous and it’s directly connected to vote by mail. We know that vote-by-mail is absolutely essential to certain communities, and we know that if it is expanded, it will likely increase participation in our election. This is a rancorous, terrible decision that is grounded in his deepest incompetence, but also his meanness. We should be frightened, but we should also be fighting.

The news is so bleak right now and we’ve touched on some pretty heavy topics. What are you hopeful about? What what keeps you going and optimistic at this time?

I know what we’re capable of as a country. I’m the daughter of two civil rights activists who were activists as teenagers. My dad was arrested when he was 14, registering black people to vote in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. We teased him that my mom was doing the same work, she was just smart enough not to get caught. They raised us to believe that we have a responsibility. But more importantly, that we have opportunity and possibility. My great grandmother, her grandparents were slaves. Her parents were sharecroppers. In 2018, I became the first black woman nominated to be governor of a major party in American history. I don’t have the luxury of bleakness because I’m a shining example of what is possible. But my responsibility is not to rest on either the successes or the challenges that I face, but to do the work necessary to make the next generation even more hopeful about what’s to come.

Watch the full live-streamed conversation below: