Minnesota attorney general Keith Ellison speaks to reporters in February.Glen Stubbe/Star Tribune via AP

On Sunday evening, as protests continued throughout the Twin Cities, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz announced that the state’s attorney general, Keith Ellison, would take the lead in any prosecutions related to the May 25 killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. It was a decision Walz said had been reached after consulting Floyd’s family. “They wanted to believe that there was trust,” Walz told reporters.

Ellison, a former civil rights activist, now finds himself playing an unfamiliar role in a very familiar crisis. As I reported in 2017, when the then-member of Congress was seeking to become chair of the Democratic National Committee, Ellison first came into his own in the Twin Cities more than 30 years ago as a community organizer and activist protesting against police brutality. If you want to understand how he’ll handle this current crisis, it’s worth revisiting what got him into politics.

A native of Detroit, Ellison was exposed early to the realities of police brutality and the militant response to riots. When he was 4, he hid under his bed when National Guard troop carriers drove through his neighborhood in 1968, amid the riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and came of age during the era of Coleman Young, the city’s first black mayor. Young disbanded the Detroit police department’s infamous STRESS Unit (short for Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets), which was formed after the riots and was accused of killing 22 people, almost all of whom were African American. When Bernie Goetz shot four black teenagers in a New York City subway car in 1984, Ellison, by then a columnist at the Wayne State University student newspaper, feared the worst:

“Remember the days of STRESS…and all the rest? Well, those days will be with us again if current trends continue,” he wrote. “Detroit has already agreed to a plan to put more cops back on the streets. But not just any cops. Cops with the notion that it’s not only OK to blow away young black men, but it’s probably in the best interest of society. And I am not attacking police officers. Prevailing opinion on this shooting constitutes a mandate from the people.”

It was at law school at the University of Minnesota in 1989 that his exposure to police brutality blossomed into full-on activism. As I wrote:

At the beginning of 1989, two incidents solidified his growing reputation. On January 25, as part of a series of raids on suspected crack storehouses, police tossed a stun grenade through the window of an apartment building in North Minneapolis. Two elderly black residents died in the resulting blaze. No drugs were found, and none of the men arrested at the building were subsequently charged. A grand jury declined to indict the offending officers.

Ellison and a few students organized a protest over the lack of prosecutions, but the day before their rally, another incident happened at the downtown Embassy Suites. The hotel was a hangout spot for college students, and on that night two parties were happening on the same floor. One was a kegger hosted by a group of white students. The other was a birthday party attended by African American students. It was a low-key gathering; one woman had brought her toddler. But when police responded to a noise complaint about the kegger, they busted up the birthday instead.

Partygoers alleged that the cops had called them “niggers.” One student at the party, a Daily reporter named Van Hayden, told me an officer had dangled him over the edge of the sixth-floor railing. He left in handcuffs, with a broken nose and a few bruised ribs.

Minneapolis was not Detroit. It had a far smaller black population that had far less political power—there was no Coleman Young to step in. But the protests over the deaths of Lillian Weiss and Lloyd Smalley, the elderly residents killed in the raid, coupled with the fresh anger over the injustice at the Embassy Suites, boiled over into a real movement. “It was a mini-Ferguson before anyone had heard of Ferguson,” Van Hayden, a University of Minnesota student whose nose was broken by police at the party, later told me. Ellison was at the vanguard of the movement:

A few days later, Ellison led about 75 people in a march to City Hall, where they stormed a City Council meeting, forcing officials to yield the floor to Ellison for a 10-minute speech. By then, Ellison was organizing several protests a week and holding press conferences to pressure Minnesota’s attorney general to launch a state investigation into the raid. Ellison demanded “public justice.”

There wasn’t any. The officers whose grenades caused the fire that killed Smalley and Weiss did not face charges—they weren’t even disciplined. Then–police chief John Laux said there was no evidence of any sort of discriminatory behavior in his force. Most of the charges against the Embassy Suites students were dropped, but the officers themselves were exonerated by an internal investigation. A civilian review board was set up, but it lacked the subpoena power that would have given it teeth.

But Ellison kept the pressure on, helping to form a group that same year called the Coalition for Police Accountability, which published a newsletter called Cop Watch. The first few issues featured anecdotes of police brutality, based on interviews members of the group had conducted and cases they’d been involved in.

“In the squad car, he continues to complain he can’t breathe,” reads one account.

Another tells the story of a victim who woke up in the hospital with “bruises on his neck from being choked.”

The organization so riled police that a representative of the city’s police union suggested officers join CPA themselves, the better to shut up the “crybabies and loudmouths” behind it. (That same union is now run by Bob Kroll, a Trump-loving cop who allegedly once called Ellison a terrorist.)

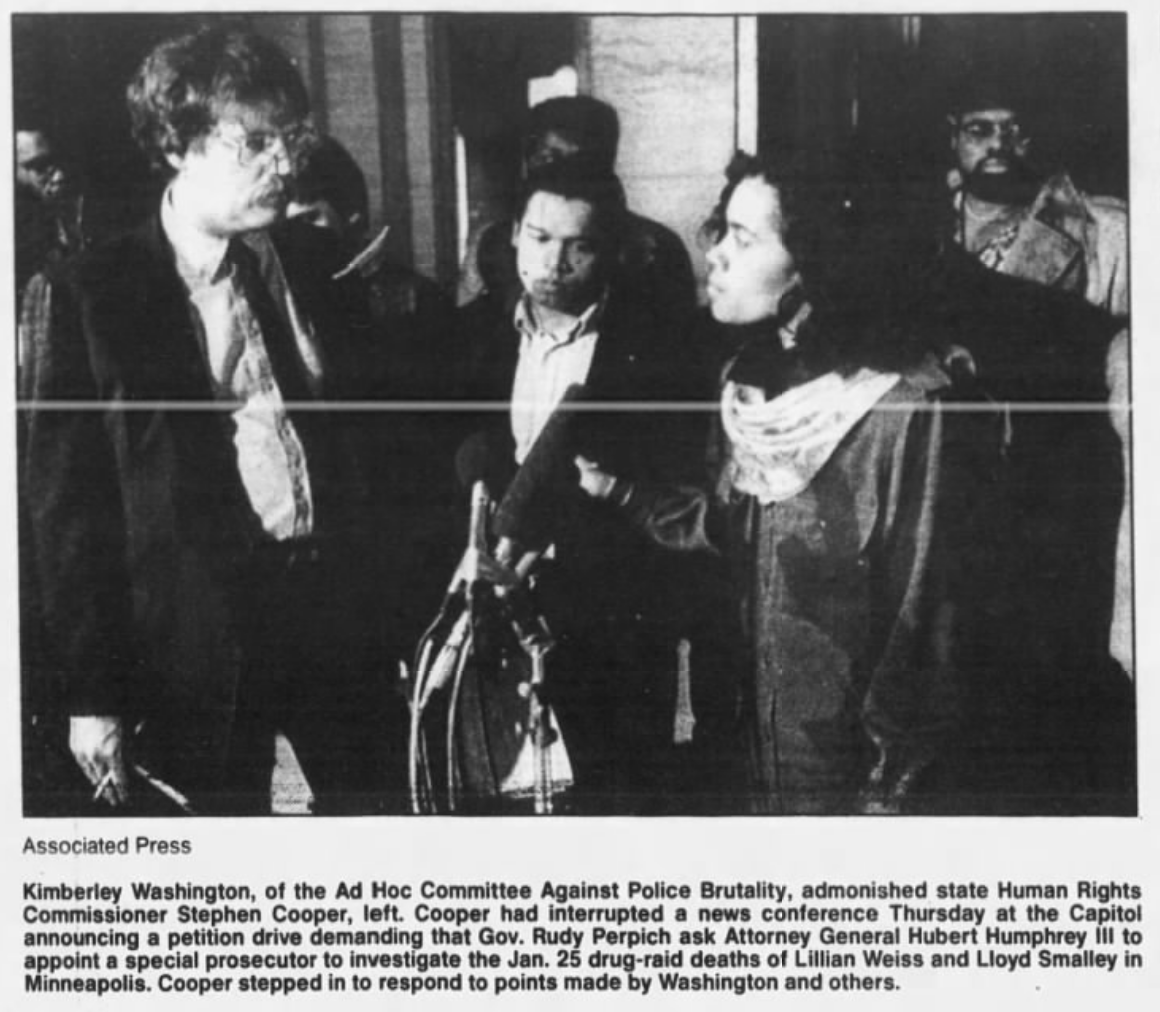

This was the activism that led him into politics, though his first run for Congress was a decade-and-a-half away. I found an old photograph from this time in the Star Tribune’s archives that feels relevant now.

Ellison and a colleague are standing at the Minnesota state Capitol demanding the state attorney general appoint a special prosecutor to investigate the deaths of Weiss and Smalley—a demand that would be summarily rejected. But Ellison doesn’t have to make those demands anymore. Now he’s in charge.