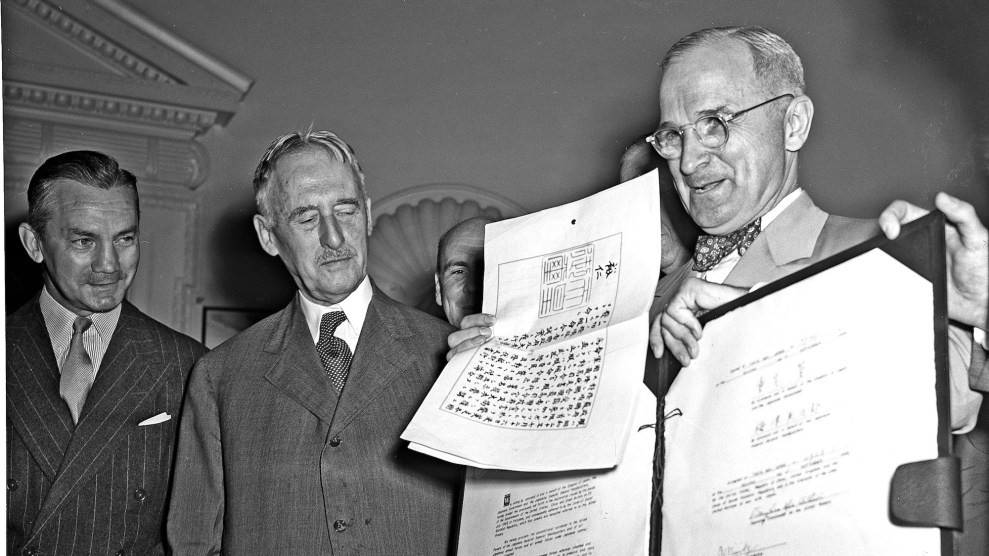

Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, center, looks on as President Harry Truman holds up the Japanese surrender papers at the White House, Sept. 7, 1945. AP photo

This article is adapted from The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (published earlier this month by The New Press).

As the world this summer marks the 75th anniversary of the US attack on two Japanese cities with a revolutionary new weapon, our opinions about those world-changing events are still being shaped by two magazine articles published a little more than a year later. One is considered a classic, read widely today mostly in book form. The other, a deliberate response published just five months later, is barely remembered at all. Yet of the two, the latter likely has had greater lasting influence on the views and official nuclear policies of Americans ever since. How that story came to be is part of the larger story of why the public, the media, and military and government leaders still support the world’s only use of the terror weapon against cities.

John Hersey’s “Hiroshima,” which filled the entire feature space of the August 31, 1946, issue of the New Yorker, has been called by many one of the most important and influential journalistic achievements of the past century. Indeed, it was greeted upon publication with overwhelming praise from readers and media commentators alike, was narrated in its entirety over national radio, and soon published as a book destined to be a bestseller.

From this one might assume—and most have—that the article forever changed the views of many Americans, including top officials and editorialists, coming as it did just over a year after President Harry Truman ordered atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing upwards of 250,000 people, about 90 percent of them civilians. It certainly did have an immediate effect on public opinion. The story, in gripping fashion, simply followed the aftermath of the horrific bombing as experienced by six Japanese survivors, their paths at times crossing novelistically. But its most important legacy might have been the response it inspired among people whose opinions were resolutely unchanged.

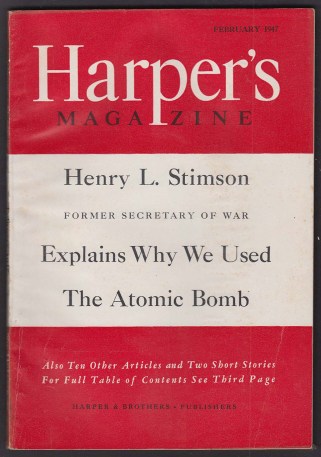

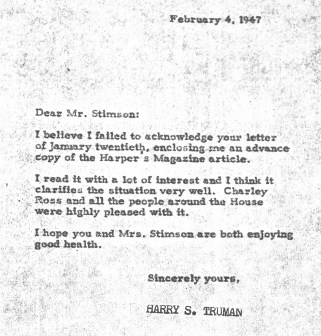

To thwart any potential shift in public sentiment against the attack, several officials who played key roles in building or using the bomb, including former Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson and Truman himself, plotted to take combative action to install their version of history. This would lead to a very different story in another leading magazine, Harper’s, to reinforce the Hiroshima narrative these men had promoted from the start—and which still holds sway now, more or less.

Harry S. Truman Presidential Library

Average Americans and the media had endorsed that assault on Japan, as it seemed to help end the bloody war, but in the aftermath the US had kept hidden almost all photos, film footage, and first-person accounts of the human effects of the bombings (including radiation disease). The Hersey article, with its unflinching account of what survivors witnessed in Hiroshima, threatened the official narrative of justification.

The view of well-respected Saturday Review editor Norman Cousins added significantly to the impact. In an editorial titled The Literacy of Survival, he asserted that Americans, despite Hersey’s achievement, still did not fully comprehend what we had done. “Have we as a people,” he asked, “any sense of responsibility for the crime of Hiroshima and Nagasaki? Have we attempted to press our leaders for an answer concerning their refusal to heed the pleas of the scientists against the use of the bomb without a demonstration?” He concluded by calling for a national “moratorium” on all normal habits and routine, “in order to acquire a basic literacy” on the moral implications of the atomic bombings and the atomic age. If this accomplished little it would at least “enable the American people to recognize a crisis when they see one and are in one.”

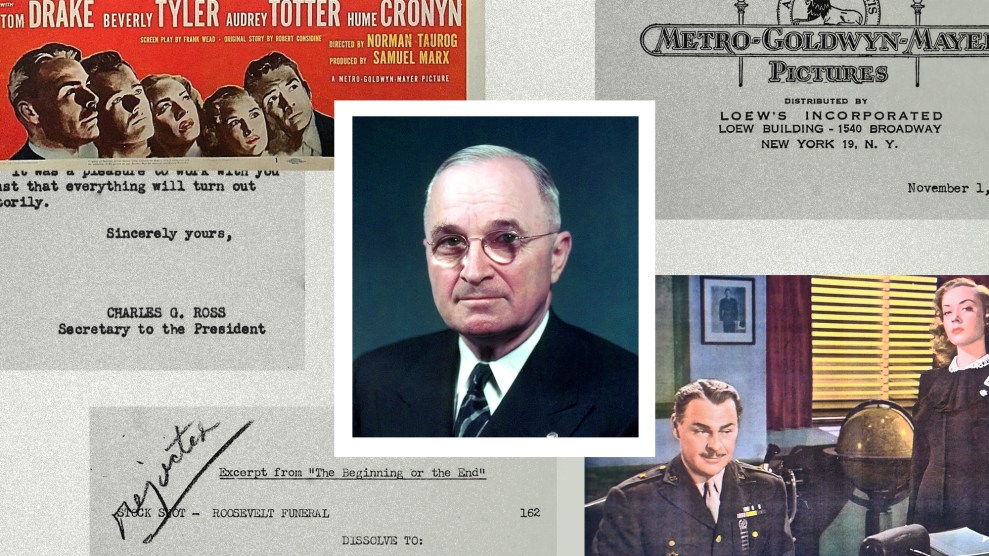

In the same period, MGM was producing the first Hollywood movie about the creation and use of the bomb, The Beginning or the End, which posed an additional threat to the official narrative, drawing the alarmed attention of Truman and the director of the Manhattan Project, Gen. Leslie Groves. They intervened in unprecedented fashion to order revisions and retakes to shape a new pro-bomb message. (This is the subject of my book, The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.)

Clearly, those who supported the use of the bomb against Japan had to respond in some way, as Hiroshima, now in book form, hit the bestseller lists. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, who played a key role on the advisory committee that recommended to Truman that he deploy the new weapon, had grown so alarmed by the threat posed by Hersey and Cousins that he wrote to Harvey Bundy, former assistant to Secretary of War Stimson. “I am considerably disturbed about this type of comment which has been increasing in recent days,” Conant explained. He warned of a potential “distortion of history” that would be passed down by “a small minority” to succeeding generations if the Hersey and Cousins writings were not challenged. It was vital that someone with great authority, such as Stimson, pen a “statement of fact,” in the form of a popular article, and soon.

Declaring he was “unrepentant” about using the two bombs against Japan, Conant even outlined the points Stimson should explore: The atomic scientists had “raised no protest” (actually not true); a demonstration shot in a remote area before using it against people was “not realistic” (debatable); and it was just “Monday morning quarterbacking” to assert that Japan was ready to surrender (in fact, several prominent Truman advisers had raised the issue before the attacks).

Stimson readily accepted the writing assignment, which he would undertake with his former aide’s son, McGeorge Bundy. Soon he would come to regret it, recalling the doubts he had harbored about using the bomb against any civilian target (especially his beloved Kyoto). He had spent some sleepless nights over the decision. If anything, Stimson was among the more dovish of Truman’s advisers on possibly ending the war without using the new device.

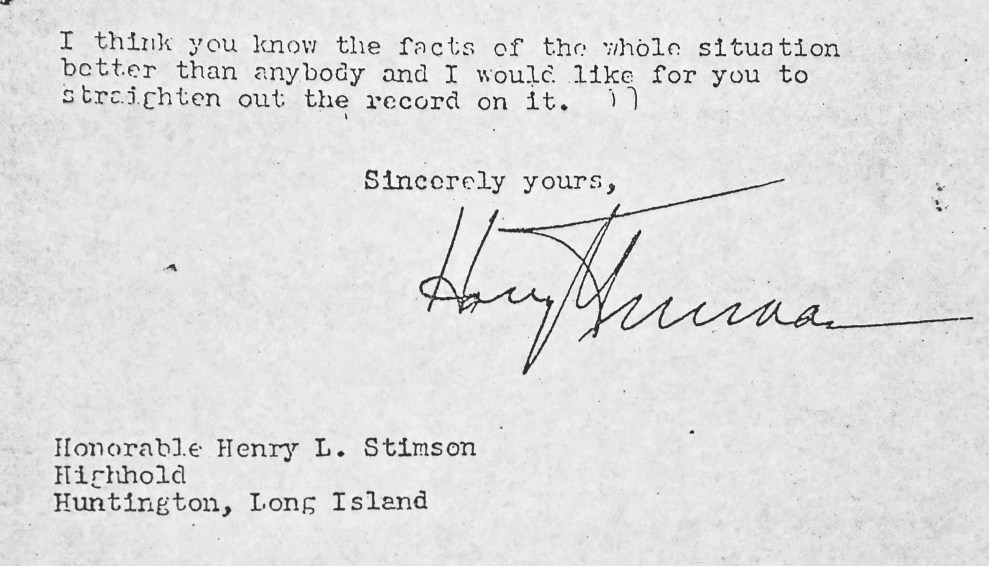

Now, more than a year later, with Stimson ambivalent about his writing assignment, McGeorge Bundy solicited rough drafts of the article from his father, from Leslie Groves, and from two others. The White House was not directly involved, but Truman surely approved, as he had separately urged Stimson to write just such a defense. (“I think you know the facts of whole situation better than anybody,” Truman advised, and Stimson should “straighten out the record on it.”) Harvey Bundy argued that the main aim for dropping the bomb was simply to save lives. Groves in his draft painted a picture of thoughtful men exercising great care in making a truly wise decision; as usual, he took wide credit for this himself. He falsely asserted that the target was always meant to be a city, “primarily military.”

Stimson and McGeorge Bundy consolidated the arguments and sent a draft to Conant for comment. Conant insisted that they eliminate any mention of the internal discussions (of which Stimson was a part) about modifying Truman’s unconditional surrender demand to allow Japan to keep its emperor—which some thought would speed a pre-bombing surrender offer. Conant rightly called this “the problem of the Emperor.” And he was so concerned readers might feel that the idea of a demonstration shot seemed fair that he wrote an insert arguing otherwise.

Conant urged Stimson to get the article published in a major magazine as soon as possible. But Stimson remained conflicted. “I have rarely been connected with a paper about which I have so much doubt at the last minute,” he told a friend. He feared that those who knew him and regarded him as “a kindly minded Christian gentleman” would, after reading such an article, “feel I am cold blooded and cruel.”

Nevertheless, his article was published with great fanfare by Harper‘s in its February 1947 issue, boosted by a cover line that promised the story would explain “Why We Used the Atomic Bomb.” Stimson had told Truman that he hoped the article would answer the activist “Chicago scientists” and “satisfy the doubts of the rather difficult class of the community which will have charge of the education of the next generation.”

Published by Harper’s in a report that filled 11 pages, Stimson’s dispassionate treatise drew wide attention partly because it revealed for the first time some of the key dates, meetings, memos, and individuals surrounding the decision to drop the bomb. Commentators on radio and in print treated it not so much as advocacy but as a statement of facts, much as Conant had hoped. Many newspapers, including the Washington Post, reprinted the entire article—Harper’s made it available to any outlet for no fee—and others quoted from it at length, often on their front pages.

In many respects it was a replay of the response to the John Hersey article. Some focused on Stimson’s estimates of one million American lives saved, the highest number (if wildly exaggerated) yet offered. The New York Times, which over the preceding 18 months had occasionally raised questions in editorials about the use of the bomb and which had lauded Hersey’s work, now endorsed that decision completely. It found the reasoning expressed by Stimson “irrefutable,” the justifications “unchallengeable.”

The New York Herald Tribune went even further in deciding the case was closed: “So much for the past.”

And so much for the Hersey article.

The Harper’s article detailed how the decision was made by Truman only after the official advisory Interim Committee had recommended that the weapon be used as soon as possible and without specific warning against a “dual” target—some sort of military installation surrounded by enough houses (“enough” meaning many thousands) to show off its pure and deadly power. A demonstration shot was judged “impractical” and risky; it might be a “dud,” making the US position worse. Japan’s surrender terms were always “vague” so Truman really had no choice. Stimson stated repeatedly that the bomb and the bomb alone had ended the war.

He did not mention even once Russia’s critical entry into the war against Japan on August 8, nor whether US concerns about the Soviet threat in the postwar years played any role in the decision to use the bomb. He downplayed attempts to end the war by modifying surrender terms to allow Japan to keep its emperor (which Stimson for a time had supported and later admitted in his memoirs might have ended the war sooner). Nor did he disclose that a leading argument for using the bomb expressed by many insiders, from Conant to Groves, was that it was “the only way to awaken the world to the necessity of abolishing war altogether.” It was Stimson himself who had stated that view, although not in his article.

With the Stimson article a sensation, Truman now informed him that he had clarified the issue “very well.” Dean Acheson told him it “was badly needed and…superbly done.” McGeorge Bundy joked that the article had reduced certain annoying “chatterers to silence.” In a letter to Stimson, James Conant expressed a heretofore hidden reason why the article was so important: He was now firmly convinced that the Russians would agree to American proposals in the atomic field “provided they are convinced that we would have the bomb in quantity and would be prepared to use it without hesitation in another war.” On the other hand, “if the propaganda against the use of the atomic bomb had been allowed to grow unchecked, the strength of our military position by virtue of having the bomb would have been correspondingly weakened.”

This pointed to perhaps the prime reason for shoring up the Hiroshima narrative: Not merely to provide the “correct” message for future Americans but to impart the proper lesson to the Soviets. So much for the past?

Around the same time, that MGM movie, The Beginning of the End, was released in theaters. The movie offered an upbeat take on the use of the bomb that was dramatically different from where the script had started, thanks to dozens of changes ordered by Groves (who had wangled script approval) and the White House. Truman demanded that MGM reshoot a key scene to portray his decision to drop the bombs in a warmer light. The president even contrived to have the actor playing him fired, claiming that he lacked “military bearing.”

Shortly after the Harper’s article appeared, the new Atomic Energy Commission held one of its initial meetings. Discussions ensued about the relative importance of focusing on strictly energy/reactor issues versus military/bomb applications, “with rather general final agreement that weapons were of first priority,” according to the minutes of the meeting. Maximum effort would be thus directed to reviving Los Alamos, conducting more weapons tests, increasing the production of raw materials for atomic bombs—and developing new devices, such as the hydrogen bomb. Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called “father of the atomic bomb” who had argued for a focus on peaceful uses, nevertheless went along quietly, telling the assembled: “It seems to me the heart of the problem has been reached with surprising speed: The making of atomic weapons is something to which we are committed.” Leo Szilard, who’d played a key role in developing the bomb and had tried to stop or delay Truman from using it against Japan, now believed only a “miracle” from God could save the day and the era ahead.

In the broader society, however, the crisis for proponents of a nuclear buildup seemed to be at an end. With the orchestrated publication of the Stimson article in Harper‘s and the denuding of The Beginning or the End, they had surmounted the temporary threat posed by John Hersey’s popular article and book and the impassioned critiques by Norman Cousins, theologians and scientists, and some journalists and military brass. “The vast majority of public opinion still stood firmly behind US atomic policy and its decision to use the weapons on Japan,” James Hershberg would observe in his biography of James Conant. Truman’s image was secured as “careful, informed, and deliberate in his decision to use the bomb.”

With that established, the scientists’ movement went into a steep spiral. With any challenges to developing bigger and better nuclear weapons set aside, American scientists, led by Edward Teller, plunged into creating a mega-device, the hydrogen bomb. The Soviets would invent and test their first atomic devices, then their hydrogen devices, and the arms race with the Americans was on and would last almost 50 years. Soon there would be thousands, then tens of thousands of nuclear warheads in the world. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, all the while, sank deeper into what the writer Mary McCarthy called “a hole in human history.”

Today, many Americans still read the Hersey report while few are even aware of Stimson’s article. Yet polls show most Americans continue to endorse the decision to use the bomb against Japan; reporters and pundits in the media rarely challenge the official narrative of the attack; and America’s “first-strike” nuclear policy remains firmly in place. Americans are rarely confronted with facts or images of what happened on the ground in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When this evidence is presented, inevitably it is surrounded by arguments for the dropping of the bomb—first presented, and rarely altered or expanded, since the Harper‘s article in early 1947. Sadly, the verdict of history is clear, for now: Stimson and the plotters behind his article won the argument.

Greg Mitchell has written a dozen books. His latest, The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, was published earlier this month by The New Press.