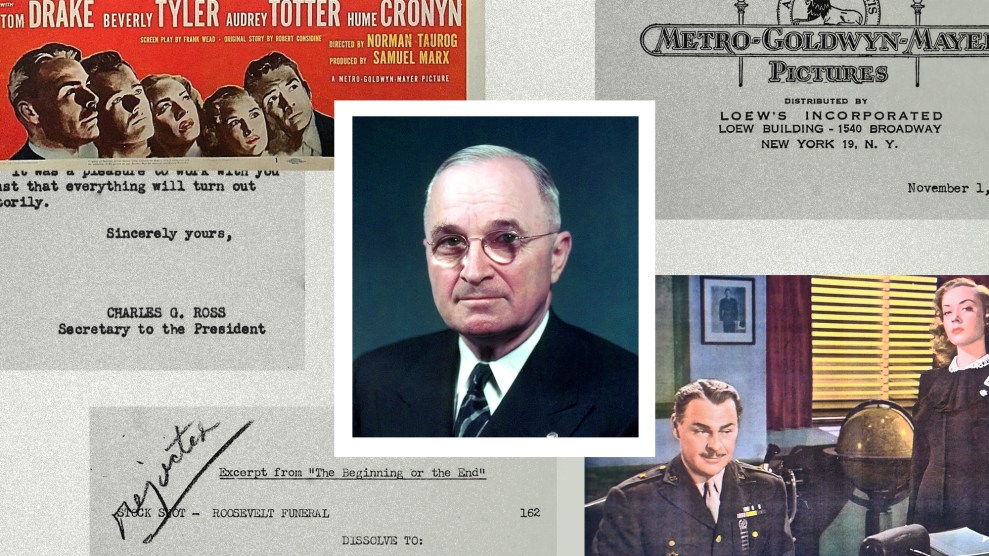

Mother Jones illustration; Wikipedia; Harry S. Truman Presidential Library; collection of Michael Barson

This article is adapted from The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (published today by The New Press).

The Washington screening for the MGM epic on the creation and use of the atomic bomb, The Beginning or the End, arrived on October 26, 1946. Attendees gathering at the Navy Building auditorium ranged from famous scientists to the country’s most esteemed newspaper columnist, Walter Lippmann, and White House aides Charles Ross and Matthew Connelly. This came at a low point for the Truman administration, as the president’s approval ratings in polls had fallen to barely half the heady 80 percent mark he enjoyed after the Japanese surrender ended World War II the previous September.

Hosting for MGM were studio executive James K. McGuinness and his DC fixer Carter Barron. The movie had taken root a year earlier when young actress Donna Reed received a letter from Dr. Edward Tompkins, her former high school chemistry teacher back in Iowa, who had worked on the bomb at the top-secret Oak Ridge site in Tennessee. He suggested a drama that would reflect the atomic scientists’ fears about further developing the bomb for military purposes, likely leading to a nuclear arms race with the Russians and threatening the future of the planet.

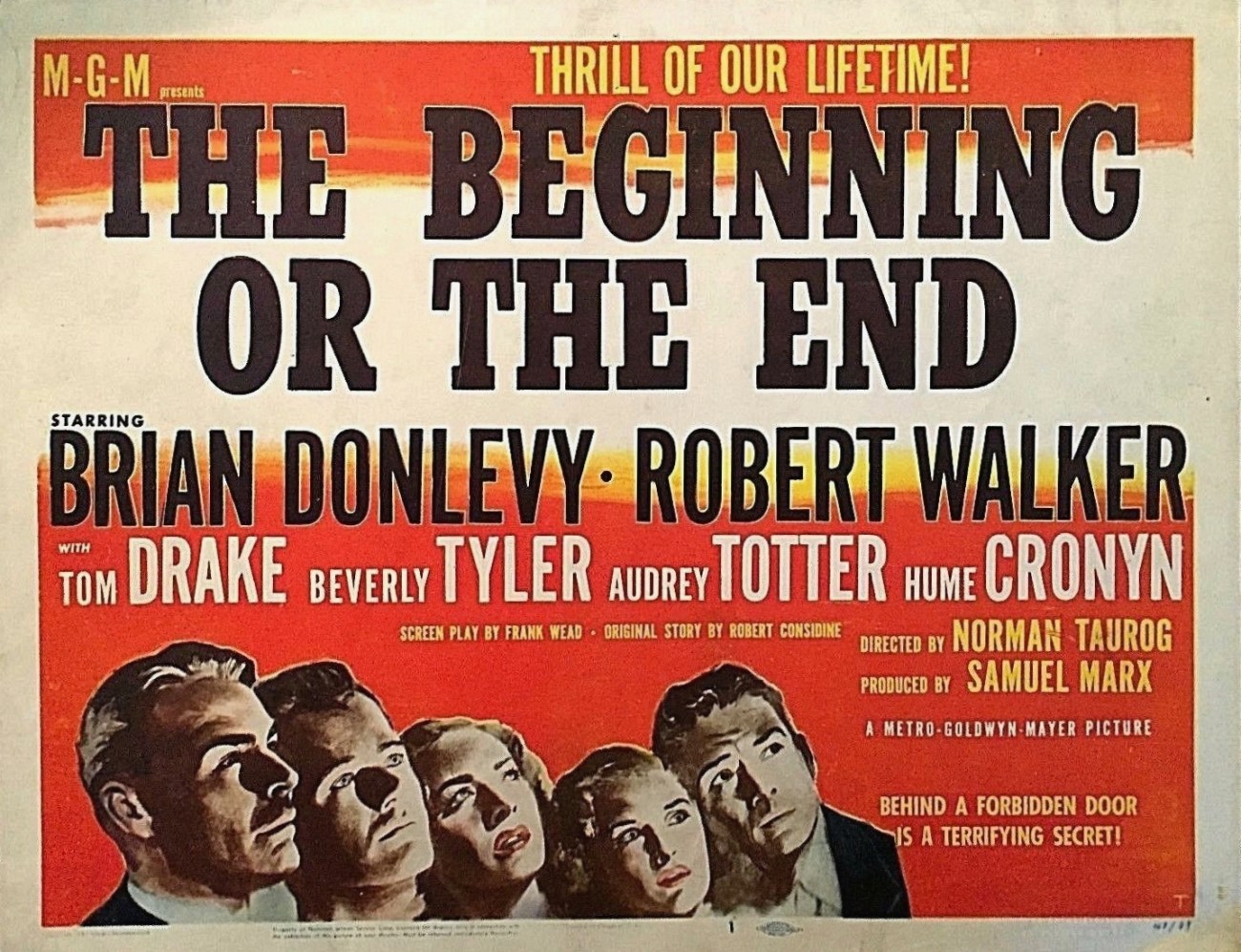

Her husband, Tony Owen, an agent, along with producer Sam Marx had taken the idea to MGM chief Louis B. Mayer, who vowed that it must become Hollywood’s “most important” movie ever, an early example of what would become known as the docudrama genre. Owen and Marx met with President Truman, who happily supplied the title for the movie when he told the two men to “make your film” but “tell the world that in handling the atomic bomb we are either at the beginning or the end.” Oscar winner Norman Taurog was hired as director, with Brian Donlevy and Hume Cronyn chosen for the leads. Over at Paramount, producer Hal B. Wallis attempted but then aborted a similar project, with novelist Ayn Rand, of all people, penning a wild screenplay in which the development of the bomb was portrayed as a triumph of individual discovery and private industry.

The first MGM scripts generally endorsed the scientists’ warnings and depicted graphic scenes on the ground in Hiroshima after the first atomic blast. The scientists did not know that MGM, in hiring General Leslie R. Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, as chief consultant, had not only paid him $10,000, a lavish fee for that time—and $130,000 in today’s value—but granted him script approval. From that point on, as his demands for edits in the screenplay piled up—dozens in all, most accepted by the studio—the message of the film shifted dramatically to fully endorse the use of the bomb against Japan and stockpiling more earth-shattering weapons going forward.

On top of that, the studio had essentially also granted Truman script approval and sent him an early screenplay, which he read. In response, his press secretary, Charles Ross, demanded that the president only be filmed from behind. He also induced MGM to cut one entire scene featuring Truman, as a U.S. senator, raising questions about the massive amounts of money being directed to a top-secret program (he didn’t know this was the Manhattan Project). MGM’s Carter Barron obsequious reply confirmed the deletions and thanked Ross for his “speedy attention” to the script.

How would influential viewers at that first DC screening in October respond to the completed movie? More than a year after the atomic attacks, Truman’s decision was finally being questioned by many in the media and among the public. John Hersey’s article “Hiroshima,” which filled the August 31 issue of The New Yorker, dominated public discussion for weeks and was about to be published in book form.

Taking a critical and potentially far-reaching view after the screening was Walter Lippmann. He wrote what would turn out to be a highly influential two-page letter to Frank Aydelotte of the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton. “The film itself bears out your own apprehensions,” Lippmann warned. Its basic theme “is not the problem of the atomic bomb in the world, but the success story of the Americans, particularly General Groves, in making the bomb.” This was made worse by the fact that the decisions to deploy the weapon “are melodramatic simplifications and, indeed, falsifications of what actually took place.” He was incensed by the scene in which Truman, acting with little deep thought shortly after he’s learned about the existence of the bomb project, orders Groves and Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take the bomb “and use it” should the first test in July 1945 succeed. Not only that, Stimson “incidentally appears in it as a doddering old man.”

Lippmann was not done. The impersonation of the atomic scientists was “highly objectionable.” It did a “great disservice to them and to science,” and he expressed surprise that Enrico Fermi, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Albert Einstein “have permitted it.” His conclusion? “The thing should not have been done at all or, if done, it should have been a documentary film with purely educational purpose. But as it is now, it is primarily not a film explaining the atomic bomb, but a film which uses the atomic bomb for a Hollywood film….I don’t know that anything can be done about it now, except to raise our voices loudly enough in objection to make people realize that this is not the wholly accepted American view of this matter.” Lippmann warned that foreign governments “will assume it represents the general spirit and attitude of the U.S. Government.”

Alarmed by the message from the godlike Lippmann, Aydelotte quickly sent copies of it to a few key people, including Oppenheimer, then in Berkeley. Oppenheimer, conflicted as usual, had belatedly signed a release to be portrayed in the movie (though a transcript of the FBI tap on his phone shows him continuing to trash it). Aydelotte advised in a cover note to Oppenheimer that “if you and your group were sufficiently insistent something could be done.”

Far from finished, Lippmann also voiced his concerns directly to James K. McGuinness. But there was one man in the audience at the screening even more powerful than Lippmann, someone who worked in very close proximity to the president. This was press secretary Charles Ross, a former newspaperman in St. Louis, who would set in motion an unprecedented White House intervention in the making of a major Hollywood motion picture.

The film that resulted would serve up many of the tropes that would mark the postwar rationalizations of the bombings and the secret project that birthed them, as well as of the arms race that would ensue. In its censored form, The Beginning or the End offered a preview of how the US would try to bolster its official “first-use” policy, which gives every president the authority to order a nuclear first strike, not merely a retaliatory blow, to save American lives, and which remains in effect today. In little-seen correspondence between the filmmakers and the White House, a different sort of large-scale national project emerges: the construction of an enduring narrative of self-justification.

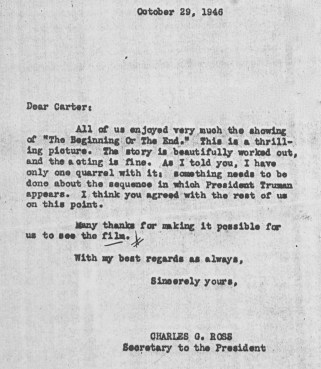

After the Washington screening, Ross wrote to MGM’s Carter Barron that he and others “very much enjoyed” the movie and found it “a thrilling picture” with a “beautifully worked out story” and fine acting. He had only one quarrel with it, but he expressed it as a demand, not a request: “something needs to be done about the sequence in which President Truman appears.”

As currently assembled, The Beginning or the End portrayed a decisive Truman—normally a good thing from the White House’s point of view. Now, Ross believed, the movie ventured too far in the direction of unthinking callousness in the decision to drop the bomb. MGM would have to walk a fine line in any retake or the White House would likely no longer approve the movie, and might even try to scuttle it.

In reality, of course, when and how the decision to drop the bomb was made remained far too complicated to explore in a Hollywood entertainment. It was “not the product of a single mind,” author and psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton would later observe. “Rather, it resulted from a series of choices, of prior decisions, made by individuals and groups involved in a bomb-centered process.” Oppenheimer claimed “the decision was implicit in the project.” Privately, Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, downplayed Truman’s contributions and claimed the starring role for himself, later asserting that the president’s “decision was one of noninterference—basically, a decision not to upset the existing plans.” He also described the unprepared Truman in that period as “like a little boy on a toboggan.”

Years later when out of office, Truman himself was asked a question concerning how long it took him to decide to use the bomb against Japan. He responded by snapping his fingers.

James K. McGuinness, informed about the new, high-level concerns emanating from two enormous power centers—Walter Lippmann and the White House—wasted no time springing into action. On November 1 he told Lippmann he had discussed his critique with the top people at the studio in Culver City. As a result, they would be making some cuts.

Most significantly: The present scene with Truman making his quick decision to use the bomb would be axed completely. “Personally, I was deeply impressed by your feeling that we were showing our country’s Chief Executive deciding a monumental matter in what was a much-too-hasty fashion,” McGuinness affirmed. In its place: a new scene set at Potsdam in July 1945 (where Truman had met with Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill) that would detail the surrender ultimatum to Japan, with Truman explaining to Charles Ross the compelling basis for using the bomb if the enemy did not quit. This would “sum up” Truman’s previous conferences on the decision with our military and with Churchill. “For your criticism of the scene you saw and your careful analysis of the dangers inherent in it,” McGuinness closed, “I wish to express my own gratitude and that of Loew’s [MGM’s parent].”

The same day, McGuinness sent three copies of the hastily written new scene to Ross, who was by then in Kansas City with the president. It’s unclear whether McGuinness, a former screenwriter, or producer Marx penned the retake. “This seems to incorporate all the matters we talked about,” McGuinness asserted, while noting it was only “tentative and I am eager to discuss it with you and to incorporate anything else you deem advisable.” (Note the anything else.) Time was now so pressing he even offered to fly to Kansas City to meet with Ross, then catch the luxury Super Chief train back to LA for the final revisions and retakes.

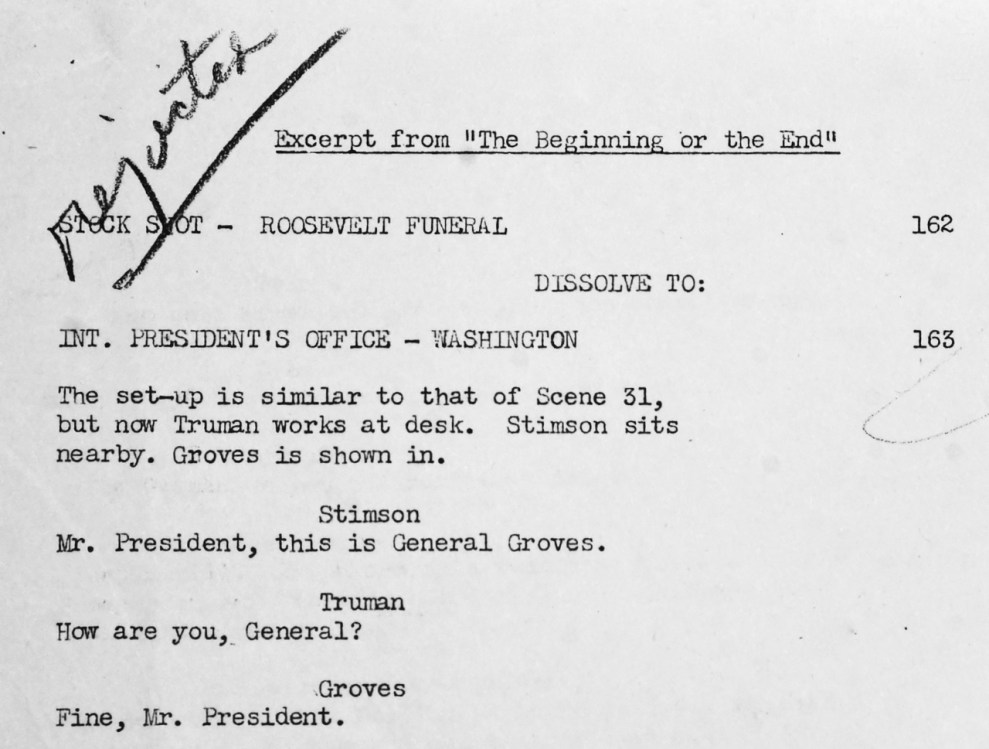

The package Ross received included a memo by McGuinness describing the setting for the new scene in the president’s sitting room at Potsdam. Dramatic lighting would keep Truman mainly in shadow with the camera pointed across the heavy, carved desk, over the president’s shoulder. Then Ross enters carrying a few sheets of paper.

TRUMAN: Sit down, Charlie….Our country, with the help of scientists from nearly all the United Nations, has developed the most fearful weapon ever forged by man—an atomic bomb….It has been tested—and it works. In peace, it will provide such power as will eventually lift most of mankind’s burdens. In war—its destructive power is as much greater than any existing explosive as an anti-aircraft searchlight is brighter than a Christmas tree candle.

ROSS: If they had it they’d use it on us.

TRUMAN: That’s a persuasive argument, Charlie—but not a decisive one.

ROSS: The whole thing is terrifying. You must have had some sleepless nights over it.

TRUMAN: Yes, it has cost me some sleep. I have had to make a tremendous decision. I’ve consulted about this every day for weeks, now. With the Chiefs of Staff, naval and military; with the Secretaries of State, War and Navy, and Mr. Churchill; with our greatest scientists. The consensus of opinion is that the bomb will shorten the war by approximately a year.

ROSS: Who disagreed?

TRUMAN: Nobody, actually. Some scientists who worked on the project think we should drop it on an uninhabited area as a warning. But the staff is sure the Japanese militarists would never let their people learn about it….The Army has selected certain Japanese cities which are prime military targets—because of war industry, military installations, troop concentrations or fortifications. We will shower them for ten days with leaflets telling the population to leave—telling them what is coming. We hope the warnings will save lives….A year less of war will mean life for untold numbers of Russians, of Chinese—of Japanese—and from three hundred thousand to half a million of America’s finest youth. That was the decisive consideration in my consent.

ROSS: As President of the United States, sir, you could make no other decision.

TRUMAN: As President, I could not. So I have instructed the Army to take the bomb to the Marianas and—when they get the green light—to use it.

Along with submitting the script, MGM notified Ross that it had suddenly decided to recast the role of Truman in the retakes. The note to Ross revealed that in the recasting “it must be emphasized that the President…is physically trim, alive and alert, and that his actions are brisk and certain.” This seemed odd, since the studio had previously bragged in publicity materials that the actor originally cast in the role, Roman Bohnen, closely resembled Truman in appearance and manner. The reason given to the press was that Bohnen lacked “military bearing,” even though he’d been shot from behind the whole time, as the White House had ordered. More likely Ross had discovered the actor’s left-wing activism—in fact, he was probably a member of the Communist Party USA. One more thing: the studio would be adding to Truman’s lapel his Bronze Star “discharge button” from World War I.

There would not be any retakes, however, until the White House approved the new script. Within days, Ross returned to MGM a marked-up script with concise but revealing edits, likely the first time any White House had been engaged in a script polish. For example, the already-inflated length of time the bomb would shorten the war increased from “a year” to “at least a year.” The peacetime uses of atomic energy, the president must now declare, would lead to “a golden age—such an age of prosperity and well-being as the world has never known.”

Ross, or the president, deleted entirely the reference to scientists calling for the bomb to be dropped first on an uninhabited target. The bit of dialogue in which Truman shares credit for building the bomb with other countries also disappeared. Gone altogether was the key line that followed Ross telling the president that he “must have spent some sleepless nights” mulling his decision. In the script sent to Ross, Truman says, “Yes, it has cost me some sleep.” Now, in this revision, Truman simply does not reply. MGM had tried to introduce the humanizing concept of a morally conflicted Truman. Now the White House was expunging the president’s acknowledgment of inner turmoil, as if to let Truman have it both ways. The sleepless-nights idea is proposed, but Truman will be free to deny it later in life—as he would, famously, more than once.

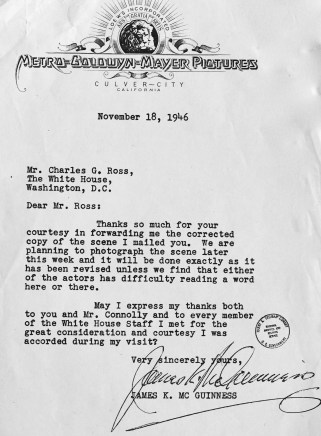

On November 18, McGuinness thanked Ross for his “courtesy” in editing—some would say “censoring—his studio’s script. MGM was readying it for the retakes “and it will be done exactly as it has been revised” (and, indeed, it would be, word for word). There was no quibbling or pushback from the normally abrasive McGuinness.

And when MGM’s Carter Barron sent the revised script for the retake to Groves he proudly noted in a letter only now coming to light, “This new treatment and dialogue was approved following a conference between Charlie Ross, Matt Connelly, Clark Clifford and the President.” So Truman was very much a part of the process (as was Clifford, soon to become one of the most influential postwar Washington “wise men”).

Walter Lippmann, learning about the planned changes, told one close friend that he had to admit that “sufficiently drastic criticism does have its effects upon the producers.”

Truman’s explicit role in making and, nearly as important, describing the decision to use the bomb had now been set in celluloid. It did omit a vast number of additional or alternative explanations from Truman himself that might have raised thoughtful questions in the minds of some viewers if they had been included.

For example, having just secured, at Potsdam, Stalin’s agreement to enter the war against Japan in mid-August, Truman exulted in his journal “Fini Japs when that comes about” and “I’ll say we’ll end the war a year sooner now, and think of the kids who won’t be killed!” This suggested that the bomb, in his estimation, was actually not needed to end the war quickly. Some of his top advisers also urged him to signal to the Japanese that they could keep their emperor after the war, which would (they believed) likely produce a surrender soon. The U.S. did endorse this—after using the two new weapons.

Less than two weeks before the bomb exploded over Hiroshima, Truman wrote in the same diary that “military objectives and soldiers and sailors are the target and not women and children,” even though the bomb would be aimed at the very center of large cities dominated by women and children. Was Truman somehow not briefed on the official targeting plans, or did he fail to take the trouble to ask about them? Which possibility is worse?

In any event, weeks later, responding to a letter criticizing his decision to deploy the bomb, he opined, “When you have to deal with a beast you have to treat him like a beast.”

The firing of Roman Bohnen from The Beginning or the End soon went public and was attributed directly to the White House, surely a first in Hollywood history. Only later would we find out how Bohnen felt. On December 2, 1946, after learning he was being replaced in the MGM movie, the actor wrote to Truman from his North Hollywood home. It was a polite but slyly critical letter. He noted Truman’s concerns about the depiction of his decision to “send the atom bomb thundering into this troubled world,” adding that he could “well imagine the emotional torture you must have experienced in giving that fateful order, torture not only then, but now—perhaps even more so.” So he could “understand your wish that the scene be re-filmed in order to do fuller justice to your anguished deliberation in that historic moment.”

People would be talking about his decision for a hundred years, he observed, “and posterity is quite apt to be a little rough” on Truman “for not having ordered that very first atomic bomb to be dropped outside of Hiroshima with other bombs poised to follow, but praise God never to be used.” His suggestion: Truman should play himself in the film! If he believed in his decision so strongly, why not reenact it himself? “Unprecedented, yes—but so is the entire circumstance, including the unholy power of that monopoly weapon.”

Ten days later, Truman responded warmly, apparently missing, or ignoring, Bohnen’s sarcasm. He thanked the actor for “suggesting to Mr. Mayer of MGM that I become a movie star,” but he had no talent for that. He then took time to defend in some detail the decision to use the bomb. After the weapon was tested and the Japanese were given “ample warning” (actually not true), the bomb was used against two cities “devoted almost exclusively to the manufacture of ammunition and weapons of destruction” (the usual distortion). “As I said before,” Truman concluded, “the only objection to the film was that I was made to appear as if no consideration had been given to the effects of the result of dropping the bomb—that is an absolutely wrong impression.” There is little in the historical record or in Truman’s letters and diaries, however, to indicate that he did give strong and repeated consideration to the human toll in the Japanese cities, to the wide release of radiation—or to the consequences to letting the nuclear genie out of the bottle in an act of war.

The Beginning or the End would open in hundreds of theaters in February 1947. Reviews were mixed at best and, while not quite a box office “bomb,” the movie was far from a “blockbuster”—to borrow from the militarized slang of the movie industry. The studio reported a net loss. After fleeing a screening in Chicago, famed scientist Leo Szilard, a key figure in sparking the invention of the bomb before becoming a leading voice against its use in Japan, offered a droll epitaph: “If our sin as scientists was to make and use the atomic bomb, then our punishment was to watch The Beginning or the End.”

Greg Mitchell has written a dozen books. His latest, The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, was published today by The New Press.