August 25, 2020, Dachau, GERMANY: Dachau Concentration Camp. Nazi camp of prisoners opened in 1933. Sculpture International Monument, 1968, by Nandor Glid .Album/Zuma

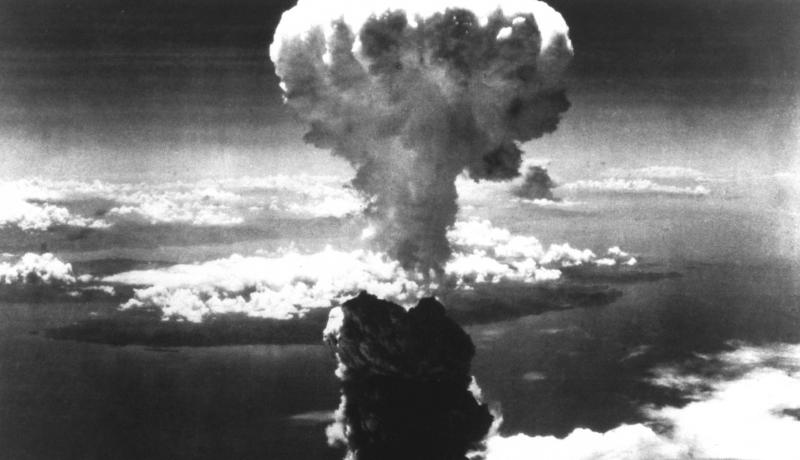

In commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, the New York Times has been running a series entitled Beyond the World War II We Know. They describe it as the “lesser- known stories from the war”—a collection of narratives by eyewitnesses who were in combat, or were victims, or were innocent bystanders, or covered the action as reporters. There was a story about a Black soldier fighting the racist Nazis only to return to the systemic racism in his own country; one with shattering photos of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Japan; another chronicling the life of a Jew in a German displaced person’s camp; and today, a remarkable diary from someone who was imprisoned for five years in Dachau, the concentration camp just outside of Munich.

Edgar Kupfer-Kobervitz’s was a Polish citizen living in Italy, a loyal ally of Germany, when he was arrested. He was not a Jew, a Communist, a homosexual, a member of the opposition—all criminals in 1940 Nazi Germany. His crime was for making some less than flattering observations about the Italian and German fascist governments, for which he was arrested. After a brief stop in an Austrian Gestapo prison, he was sent to Dachau. For the next five years until he was liberated by the Americans, he kept a diary of the quotidian horrors he and others experienced there. According to the Times, “By the time Dachau was liberated by American forces, in April 1945, Edgar had written more than 1,800 pages.” Miraculously, they survived. As the Times notes:

While the number of postwar memoirs written by survivors of the Holocaust is enormous, the number of testimonies that were actually written inside German concentration camps is far smaller. The ones that do exist are often fragmentary, and almost none show Edgar’s extraordinary powers of observation in analyzing the unique and hellish universe that was the Nazi concentration camp.

In that hellish universe, Kupfer-Kobervitz called it “a satanic world,” exhausted prisoners in a camp orchestra would be forced to entertain their guards, they would be hung by their arms strung up behind them in a torture device called “the Tree.” They would be forced to undergo medical experiments. He kept writing for years, the diary eventually becoming so large,

[I]t was no longer easy to hide—and such a valuable testament that Edgar was anxious for its safety. One of his co-workers, a man named Otto Höfer, whom Edgar described as “a thousand percent safe,” offered to dig a hole in the concrete floor in another part of the factory, where the diary could be buried for posterity. To help preserve it from damp and decay, Edgar wrapped the manuscript in layers of oil paper, followed by aluminum foil and fabric. Otto lowered the bundle into the floor and sealed the hole with fresh concrete, in a spot where it was hidden under a rack of hundredweight iron bars. “The manuscripts,” Edgar wrote after liberation, “were hidden in the womb of the earth.”

Dachau, which had the distinction of being the Reich’s first concentration camp, was created by Heinrich Himmler in 1933 on the site of an old World War I munitions factory. It was not an extermination camp like Auschwitz or Bergen-Belsen, nor was it populated mostly by Jews. This was where homosexuals, gypsies, pacifists, common criminals, and political prisoners were located, a spot where the torture and imprisonment of so-called misfits was first systematized by the government. The German press had written about it as a humane place for disposing with these dregs of society. After the camp was liberated in April of 1945, and when the trials of those who had created that hellscape took place several months later, this diary became a valuable piece of evidence.

I was drawn to Edgar Kupfer-Kobervitz’s story for reasons beyond the garden variety historical curiosity that impelled me to read the others. In the same way that for some people a whiff of Old Spice or a reference to the Brooklyn Dodgers when they still played in Brooklyn evokes the vivid posthumous connection with a father, for me, it’s Dauchau. My father, Aladar Szegedy-Maszak, was prisoner number 125739 at Dachau. He had been the head of the political division of the Hungarian Foreign Ministry—Hungary was a German ally—and had tried (unsuccessfully) to negotiate a separate peace with the Allies. After the Germans invaded their rather unreliable ally on March 19, 1944, my father was arrested. He first served time in a Gestapo jail in Budapest until he was moved to Dachau in November.

Within the first few weeks of his arrival, he learned a few survival strategies: Don’t drink the water. Eat slowly. Avoid transports. The authorities at Dachau had become experts at sorting prisoners who were infirm—they were dispatched to one of the extermination camps— from those who might still have some strength to work. He ended up being assigned to a medical experiment. Once the site of some of the gruesome Nazi doctor experiments in which, for instance, prisoners were placed in an altitude simulator where they would be exposed to crushing pressure and then drastic drops in pressure, or hypothermia experiments in which they were strapped in freezing water while doctors measured how long it took for them to die, or infected with malaria and left to die, things had become less crazy when my father was a subject. He was in a blood clotting experiment; he was injected with a serum to see how quickly his blood clotted. If it worked, doctors thought, it might be a life-saver on the battlefield. He also had to make buttonholes in tent canvases. He also ended up getting typhus and nearly dying.

When the typhus epidemic struck the camp, Kupfer-Kobervitz was working at a factory where he and the others were quarantined so they too would not get sick. The Times explains:

This new living arrangement afforded Edgar the opportunity to sneak back into his tiny closetlike office and write while his fellow inmates slept. To avoid detection by the guards, Edgar sealed the cracks around the door so that no light would escape. He would write until 2 or 3 in the morning, exhausted, in constant fear of discovery, near collapse in the airless room.

I remember first hearing about the fact that my father was in concentration camp. I was the youngest of three and my brothers and I were in the back seat as we were driving to some family vacation spot. He spoke about it in a matter-of-fact way, and though I was very young, it dawned on me for the first time that good people could go to jail.

The themes from his life 75 years ago seem strangely relevant today: the courage to stand up for what you believe, innocent people going to jail, coping with an epidemic, leadership intoxicated with its own power, the experience of living in the midst of a terrible time with no clear end in sight. I wonder what Kupfer-Kobervitz and Szegedy-Maszak might have said were they alive today. I like to think that given their survival, the message would have been one of hope.