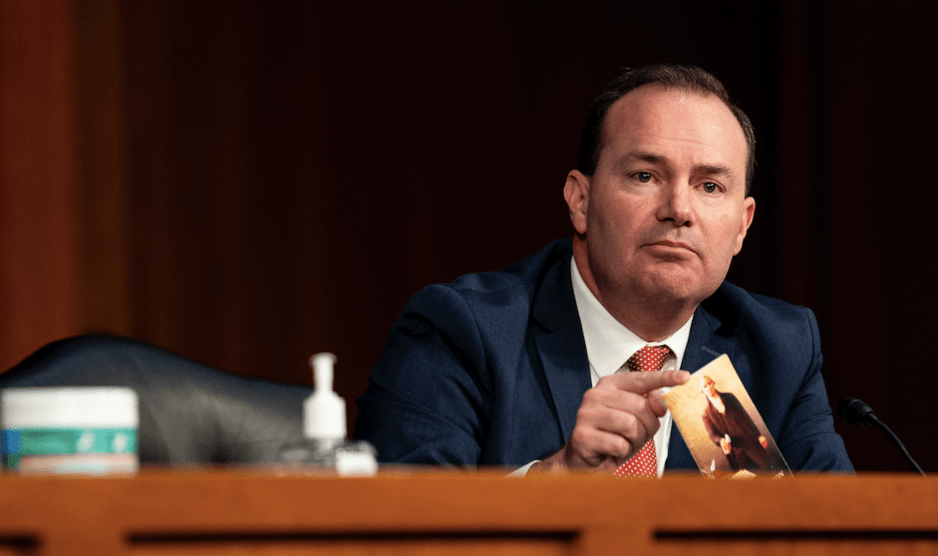

Yuri Gripas/AP

This week, the Senate Judiciary Committee is holding confirmation hearings for Supreme Court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, President Donald Trump’s pick to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg who died last month. Judge Barrett is being presented to the American public for a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court as the pinnacle of white womanhood. A woman with seven kids, two of whom are Black, and still manages to hold down a job is being exalted for her superhuman accomplishments.

For Trump and the Republican Party, who are never too far away from being legitimately accused of racism or sexism, a white working mother with Black children is a godsend, a status that protects her from criticism like a force field. But despite the endless stream of praise and adulation from conservatives, being a privileged white woman with Black kids hasn’t made Barrett immune to racism—it’s made her completely blind to it.

Part of the problem is the limited understanding of what racism, sexism, and feminism really means. After being co-opted by corporations looking to cash-in on all those empowered feelings, feminism often has been stripped down to simply mean “if a woman does it, it is good.” And too many people still believe that as long as they’re not an active member of the Ku Klux Klan, they couldn’t possibly be racist.

The low threshold means that Barrett can use her Black children to deflect any criticism about her approach to racial justice issues, and the very fact that she’s a working mother indicates she embodies a triumph of feminism. Despite spending decades pushing for policies that actively harm Black people like undoing housing discrimination protections, and policies that relentlessly undermine women’s reproductive rights, the GOP’s presentation of this nicely-dressed version of racism and sexism allows them to sleep well at night, secure in a lifetime appointment to the Supreme Court. In turn, when any liberal or Democrat asks questions about race or gender, conservatives’ pearls are never far from being clutched. How dare you? She has Black kids! It’s the new iteration of, “I have a Black friend.” By the same logic, a man can’t be sexist if he has daughters. (How many times have we heard that one?)

If there were any doubt that Democrats were grasping at straws, Cory Booker asked a mother who adopted two Black children whether she is a white supremacist sympathizer.#ConfirmACB

— Ronna McDaniel (@GOPChairwoman) October 13, 2020

It’s an incredibly naive understanding of racism. To really appreciate her approach, consider Judge Barrett’s opinion on a racial discrimination case. In 2019, Terry Smith, a Black man in Illinois was fired from his job as a public transportation worker. He later sued alleging racial discrimination, and part of his complaint accused his white supervisor, Lloyd Colbert, of calling him a “nigger.” Barrett sat on a panel of three Seventh Circuit judges that ruled to uphold the firing. “The n-word is an egregious racial epithet,” Barrett wrote. “That said, Smith can’t win simply by proving that the word was uttered. He must also demonstrate that Colbert’s use of this word altered the conditions of his employment and created a hostile or abusive working environment.” Here she is arguing that simply being called a “nigger” by one’s boss does not create a hostile or abusive working environment. She then says that while Smith testified that he’d suffered psychological distress, it was for reasons unrelated to his race. After all, his track record had been “poor“.

Putting aside all the mechanisms of the justice system that make these kinds of cases notoriously difficult to win, this ruling also shows a fundamental misunderstanding of how racism functions in the workplace—and it’s downright frightening for someone who is raising Black children. Not once, apparently, did it cross Barrett’s mind that perhaps Smith had a “poor track record” because his supervisor was racist.

Her troubling views on race, however, can be explained away by the presence of her Black children. As Senators endlessly praise her, Barrett has emerged as a near-martyr, for her courage and generosity in having a brood of children, some of them rescued from a poor, godforsaken “shithole” like Haiti. (Lest we forget how the president who nominated her described her children’s place of origin.)

Haitian culture places an enormous value on the extended family. My parents are from Haiti, and it’s fairly common for Haitian children who lose their parents for whatever reason to be raised by aunts and uncles and other relatives. For several years as a child, I lived with a cousin and would sometimes refer to her as a sister. In fact, “extended family” has such an expansive definition that even people who are not blood relations are often considered as cousins.

Many transracial adoptees have spoken about the damage done to them by well-intentioned white parents who simply had no idea how to talk about race. “I have constantly felt uncomfortable in my own skin,” Kendra Rosati, a woman adopted from South Korea told NPR’s Code Switch in 2018. “And when I was young, at night, I would pray to God that I would wake up looking just like my sisters. My parents were definitely not ready or equipped to raise a child of color. They didn’t know how or want to talk about race.”

Barrett’s preparation of lack thereof for talking about race with her children is clearly not the point. What is the point, however, is that she can use her status as white mother with Black kids to her advantage, the warped and superficial definitions of what constitutes racism, sexism, and feminism shielding her from probing questions, much less criticism, about her approach to some of the biggest questions about social policy in this country. For Senators questioning Barrett, her white motherhood appeared to be kind of intoxicating. Even Democrats, sitting in a possible COVID hot bed with the nominee being rushed through three weeks before the election, couldn’t help themselves. Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s (D-Calif.) first question to Barrett was about her children, and she continued to comment on them throughout the hearing.

Just imagine if that adoration was extended to other mothers of Black children. They are instead routinely shamed for having multiple children, accused of being welfare queens, and the sheer number of multiple children calls into question their ability to take care of them at all. Black mothers are discriminated against when giving birth, leading to dismal maternal health care and a disproportionate maternal mortality rate. Black mothers face jail time for firing warning shots at their abusers, for leaving their children in a car because they had no childcare when they went to a job interview, and for using a different address to get their children into a decent school district. Black mothers routinely watch their children being killed by police and then harshly judged by the court of public opinion for the crime of dying while Black.

The list of injustices feels so endless that it can be suffocating at times. Ask any Black person why they can’t breathe.

In perhaps in one of the most telling moments, Barrett revealed that she doesn’t even understand the weight of racism that rests on the shoulders of Black people. When answering a question about George Floyd, Barrett said she cried with her 17-year-old Black daughter when he was killed, as they grieved for him. But then she added an observation that demonstrates just how little her proximity to Blackness has helped her truly understand racism. “My children to this point in their lives have had the benefit of growing up in a cocoon,” she said, “where they have not yet experienced hatred or violence.” And I thought they lived in the United States.