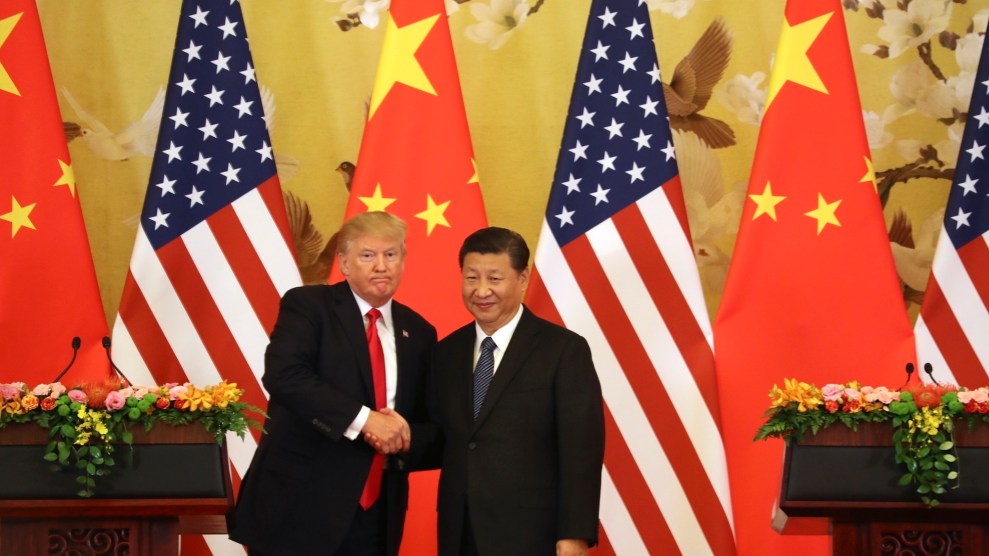

Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2017.Andrew Harnik/AP

The latest revelation from the New York Times coverage of President Donald Trump’s tax returns is that he has a bank account in China—one that has never before been mentioned. How did that happen?

While the Times has gotten a hold of Trump’s tax information, he has long refused to provide it to the public, despite decades of presidential tradition and precedent. When asked for his tax returns, Trump often tries to obfuscate by pointing to his personal financial disclosure, a form required to be submitted by presidential candidates and federal office holders. Trump likes to brag about how long his form is. And it is long, and does include a lot of information—but not enough.

The exposure of Trump’s Chinese account again underscores why the public needs to see presidential candidates’ tax returns. Without them, the disclosures provide some information on what they own and owe, but the details of how they got those assets and liabilities are hidden.

According to ethics experts, the law requires Trump to disclose all of his assets, debts, and income in his personal financial disclosures. But he doesn’t have to disclose the details of his business operations. So, while Trump has reported having bank accounts, he didn’t have to say that one of the hundreds of LLCs he owns personally—Trump International Hotel Management—has a Chinese bank account.

“Filers do not have to disclose business-related debts or business-related assets. Strange as that may sound, and counterintuitive as that is, that is the guidance from the Office of Government Ethics,” says Kathleen Clark, a law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. So, Trump has to disclose he owns a business, but not whether the business has bank accounts or loans.

Trump surrogates, like his son Eric Trump, have attempted to play down the revelation of the Chinese account, saying that the president “once looked at deals, long before politics,” but the Times piece makes it clear that he made a concerted effort to make money in China as recently as the early days of his 2016 campaign when he was negotiating with a potential partner (according to the Times, the deal fell apart when the partner was snarled in a corruption investigation). The Times cites that one of Trump’s LLCs, THC China Development LLC, claimed $84,000 in deductions in 2012, and paid fees and taxes more recently—transactions showing that Trump’s financial interest in China was not “long before politics.” While THC China Development LLC has been listed on Trump’s personal financial disclosure forms, showing whether or not it was active can only be done with the details provided by the president’s tax returns.

In that way, the Times story raises more questions than it answers. On his personal financial disclosure, Trump has numerous LLCs apparently designated for overseas projects that never happened—but, like with THC China Development LLC, is there more to their stories?

For example, according to the personal financial disclosures, in August 2015, several months into the Trump presidential campaign, he created a series of companies that, based on the name, indicate he was exploring a possibility of opening a hotel in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, the gateway to Islam’s most holy sites, Mecca and Medina. The sites are a massive tourist draw, and tourism in Jeddah is an enormous industry—and one that would be difficult to break into without at least the assent, if not the involvement, of senior members of the Saudi royal family. Like the Chinese LLC, the Saudi LLCs don’t appear to have ever generated income, but the personal financial disclosure forms are silent about how far Trump progressed in his talks with possible Saudi business partners, or who those partners were. Trump’s tax returns would help fill in those gaps.

The Times revelation about the Chinese bank accounts worries ethics experts like Clark and Kedric Payne, general counsel and senior director of ethics at the Campaign Legal Center, an ethics watchdog group.

“There’s always concern with whether or not this is a complete disclosure of all his financial interests, so there is definite concern that this is not the final picture,” Payne says.

“The larger point,” he says, “is that a president should divest of all his interests because otherwise you have these inherent and incessant conflicts.”