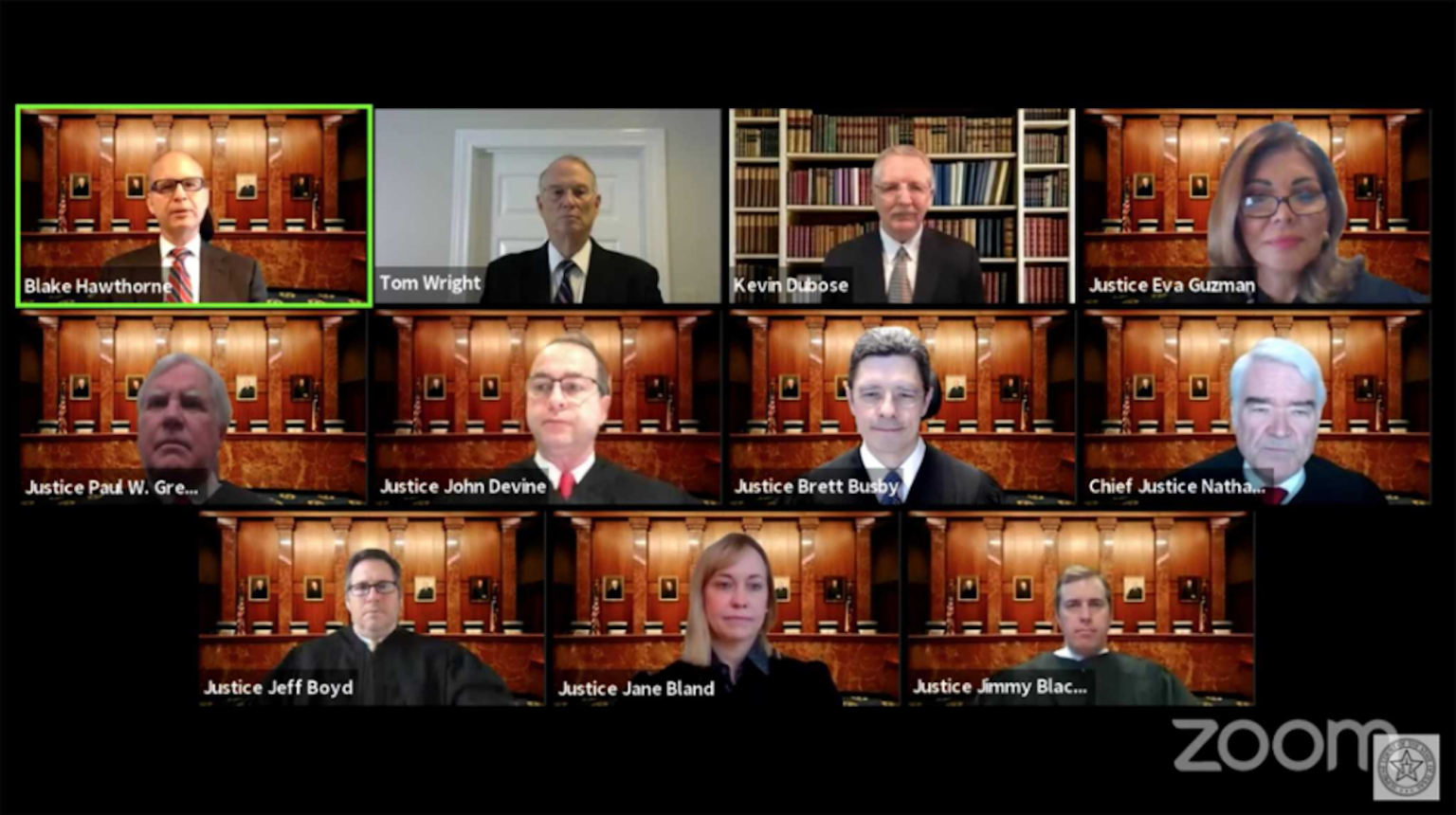

This photo of the Texas Supreme Court gives me the smallest drop of hope, like the water they found on the moon:

I know what you’re thinking: Isn’t the Texas Supreme Court a retrograde, anti-democratic misery pit built to notarize right-wing dictates? Sure. I realize that the Southern state courts are not affiliated with hope, and if they could would rule it unconstitutional.

But it is very good that these courts—Texas, Arkansas, Georgia, Florida among them—are being forced to carve out some kind of legitimacy over Zoom.

Through geographic remoteness and other kinds of physical inaccessibility, through smug obscurantism, through pageantry and grand architecture, the courts (and other institutions) have wormed into our brains the sense that they are Over There: that the state is somewhere up and off and to the side, can’t be touched, can’t be made to change except on its own terms, through a maze of bureaucratic horseshit.

In fact, the courts are a bunch of bespectacled dorks in graduation clothes who needed a 25-year-old clerk to help them find the “Virtual Background” function. The internet, long at odds with our democratic institutions, has poured into the pandemic cracks and split them open a little wider. We see our legal system through a mirror, darkly; Zoom court is Windex.

How many of the people who called in to berate LA’s police commission could have made it down to an in-person hearing? For eight-plus hours, the commission was just a handful of little square heads facing off with the citizens grilling them. For everyone who was there only because Zoom court (or its equivalent) made it possible, we squeezed some extra democracy out of the circumstances.

I lean kumbaya in the conviction that when it is easier for people to talk, it is easier to do little-d democracy. It is easier to bridge the great gaps of distance, language, social position, class background, identity. And it’s easier to see that these are just little people in their little homes, now visible in one-to-one real-life scale. This picture does more to demystify the state than one thousand journal articles. There’s no gravitas here.

Look at this photo and see a vision of the future: the normalization of citizens’ assemblies conducted from home, Zoom city council, Zoom school board; all kinds of political deliberation made slightly more manageable for working families, busy parents, the young and dispossessed, the old and poorly mobile. We could finally figure out online voting. We could have prefilled online taxes. We could take up Zoom grievances with public officials. So much of the potential for political change rests on our perception of what’s legitimate.

Problems of access won’t go away. Technology solves some, creates others. But we can choose to lean into this potential and build on it. If the US had put its back into direct democracy and citizen participation half as hard as it’s leaned into voter suppression, we’d already have robust ways to do a little home democracy.

I hate email, I hate Slack, and I hate it when you call. And yet communications technology really has dragged us an inch or two forward. It has created democratic potential energy that thrums and waits to be realized. There is always resistance—the judges would never have done this if their lives weren’t under threat from COVID—but once it’s done, it’s done. We’ve shown it’s possible, and that has lasting effects.

Much of that resistance comes from people who are vested in the old ways, whether by money, roles in powerful institutions, or both. Bankers stayed using Telex long after anyone else did; Japanese offices are the last bastion of the fax machine; courthouse sketch artists are a charming relic, but it’s not cool that you can’t see and seldom hear the Supreme Court. Put that shit on C-SPAN.

Movement organizing has always jumped on new ways of getting humans in touch. That work is about counteracting the atomization of people—knowing that others can and will react to injustice with equal passion, are prepared to take risks alongside you, share a core piece of a sense of justice. Isolation, fragmentation, mystery, obscurity, and non-communication are all always to the benefit of the powerful.

In spite of pervasive surveillance, 21st-century protest movements can coordinate in a way that opens more doors than it closes: on the local level, mobilizing people on the streets with unprecedented effectiveness; on the global level, coordinating international political action.

A lot of technology is bad, not in a Ted Kaczynski sense, but because human thriving was a footnote in the specs. The internet we know started at the Defense Department. DARPA didn’t mean to introduce new ways for ordinary people to build power around human concerns. They meant to commission military technology. That we still ended up with all this emancipatory potential tells you something pretty dope about humans. Think about that the next time someone lectures you on “human nature.”

Viva Zoom court. —Daniel Moattar