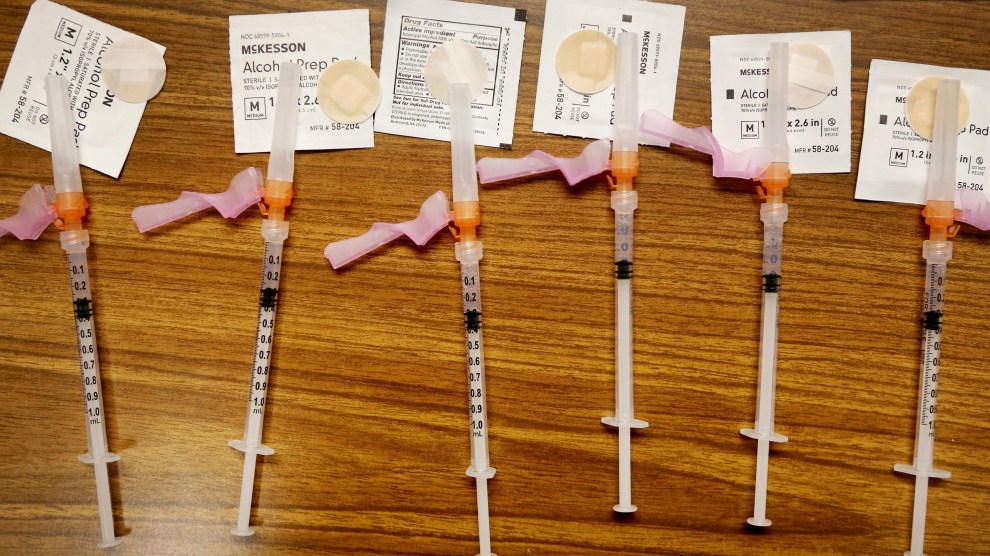

January 5, 2021, Clearwater, Florida, USA: Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines rest on the desk of RN Toni Martin who was administering the shots at the Clearwater Health Department's clinic.Douglas R. Clifford/Tampa Bay Times/ZUMA Wire

Just a few weeks ago, Americans cheered as the first coronavirus vaccines were shipped from warehouses to hospitals and health departments across the country. But the optimism was short-lived: Reports suggest that the rollout program is uneven and chaotic. Jen Kates, senior vice president and director of global health & HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, is tracking states’ vaccination enrollment efforts. She found that a Sarasota, Florida, public health department used Eventbrite to sign up vaccine recipients, while some districts in Georgia used SurveyMonkey. Elsewhere, unsuspecting supermarket shoppers have been surprised when pharmacists flagged them down to offer a vaccine because someone didn’t show up for an appointment.

Then there’s the opportunity costs of vaccinating people. In Georgia, the DeKalb County Board of Health has temporarily canceled all COVID-19 testing because the state health department needed to redirect resources to vaccination. “Based on our more emergent need to immunize our health care providers, our first responders, and our long term care facility residents, right now that is our top priority,” spokesperson Eric Nickens told me in an email. “We are actively working with DeKalb County Government and the Georgia Department of Public Health to bring on additional personnel as quickly as possible, to meet our rapidly evolving staffing needs.” The same thing is happening in other Georgia health districts.

These disparate reports of vaccination mayhem are not isolated examples of the individual disorganized bureaucrats dropping the ball. Rather, they’re part of a larger pattern: Despite Trump’s assurances since the early months that the pandemic would end swiftly once the vaccine arrived, his administration failed to develop any kind of comprehensive rollout plan. What exactly they were doing for the last ten months while scientists perfected astonishingly effective shots is a mystery, but Peter Hotez, a virologist and vaccine researcher at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, called the rollout campaign so far a “major disappointment.” Fixing this problem is the critical challenge that Biden will inherit as he attempts to vaccinate 100 million people in the first 100 days of his administration.

“The Trump administration never had a plan, so we came up small in everything—we weren’t able to handle testing, we weren’t able to do any genomic surveillance,” he says. “The only plan was to vaccinate our way through this, but now we’re realizing there was no plan for that, either.”

The problem, quite simply, is that the Trump administration thought only about vaccines and not vaccinations. There’s an old public health adage, “Vaccines don’t save lives, vaccinations do.” The federal government may have figured out how to coordinate the shipping of refrigerated vials from warehouses to health departments and hospitals—and then they left the rest up to the recipients, said Tom Frieden, former head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Frieden, who now runs Resolve to Save Lives, an initiative of the global health organization Vital Strategies, believes the federal government stopped short of creating an actual vaccination campaign. “The Operation Warp Speed leaders talk about the temperature and the restocking program, they deliver to states, and then it’s the states’ job,” he told me. “That’s not a vaccination program, it’s a grocery delivery program.”

Even the states who had vaccination plans in place have had a hard time implementing them because before the stimulus was passed in late December, they simply couldn’t afford to. “The money was needed months ago,” Frieden added. “The same people that are overwhelmed with cases are being asked now to run the most complicated program in American history.”

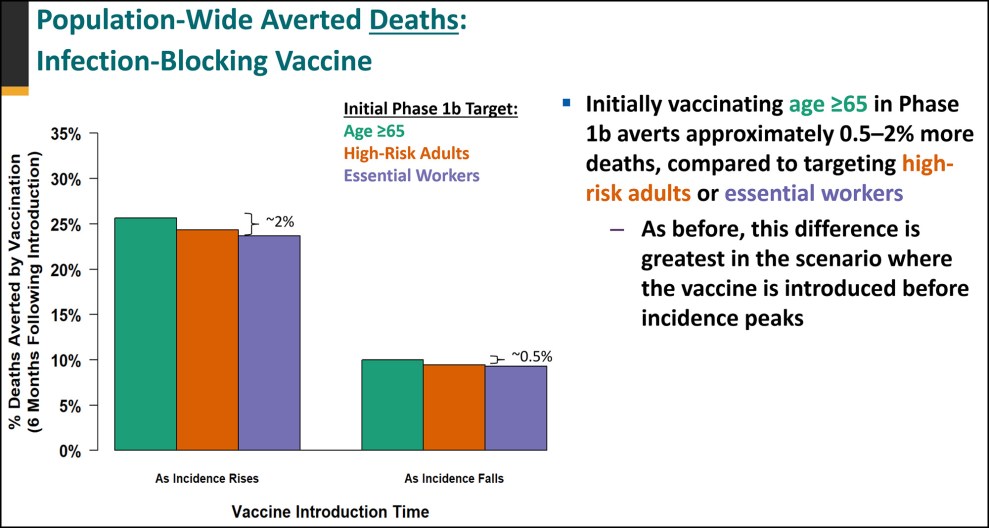

Hotez took me through a mathematical exercise: Dr. Anthony Fauci has set the goal of vaccinating 75-80 percent of the population by fall of this year. That’s about 263,000,000 people. If you figure in two doses, we’ll need to vaccinate between 1 and 1.5 million people every day starting now. Considering we’ve only vaccinated about five million people since mid-December, that’s a tall order.

Saad Omer, a Yale University epidemiologist and expert on vaccination campaigns, told me he hasn’t been surprised by the slow start. All public health campaigns begin with hiccups, he explained, and the scale of this one is massive and unprecedented. The devil is in the most banal details: If you set up a mass vaccination site, where will people park? How will health departments handle the billing? Still, Omer wonders why the federal government didn’t start planning much earlier. If the Trump administration had pushed for a national plan over the summer, he said, “the CDC could have pushed hospitals to run simulations in September or October.” He pointed to specific examples of time wasted. When New York state was convening an independent committee to review the vaccines that the FDA had approved, he said, they also could have been surveying communities, figuring out what they’d need to get residents vaccinated.

The question now is whether the vaccine effort can be salvaged. If the Biden team wants to hit the vaccination targets, they’ll have to ramp up at a precipitous pace. The experts I spoke to all agreed that the state-by-state approach won’t be adequate. We need a deeply coordinated national response, and that, Frieden said, requires a strong leader. As an example, he pointed to career public health expert Ron Klain’s work under President Obama during the Ebola crisis in 2014. “He was like the conductor of an orchestra—that’s been strikingly absent in the current administration,” he said. Frieden hopes that Biden’s COVID-19 czar, Jeff Zients, fulfills this role. He also noted the importance of reviving the credibility and morale of the CDC, which will play a lead role in coordinating the vaccination effort. “For the past ten months CDC has been undermined, sidelined and ignored by the administration,” he said. “This is an opportunity to get programs to catch up.”

In order to be successful, both Frieden and Omer said the national vaccination plan will have to take into account the needs of specific communities. Some health departments may be able to run an efficient vaccination program through existing infrastructure such as commercial pharmacy chains. Others might require a corps of workers trained to administer vaccines. Each county will have to figure out how best to equitably distribute vaccines, ensuring that vulnerable communities aren’t left behind.

If the Biden team wants examples of how to do this, they should look to states that have already set up systems that privilege communities hardest hit by the virus. Kaiser Family Foundation’s Kates says that she’s been impressed with vaccine equity efforts in states known for enacting progressive policies—Massachusetts and California, for example. She was more surprised to see these efforts pop up in some more conservative locations. Tennessee’s plan, for example, explicitly prioritizes areas that are already at a health disadvantage according to the CDC’s social vulnerability index. Kates hopes that the federal plan will learn from these early examples and encourage health departments to set up mass vaccination facilities in neighborhoods where people are likely to face barriers to accessing the vaccine. “We know those structural inequities have affected who’s gotten sick from this,” she says. “Going into vaccination you’d want to mitigate those inequities, not intensify them.”

As we move from vaccinating healthcare workers into the next priority groups over the coming weeks, experts told me this project will only become more complicated. This campaign will present the incoming administration with a colossal challenge that could set the tone for the new president’s entire term. If Biden is to succeed, the fist step will be to turn vaccines into vaccinations.

This story has been updated.