Ishmael Reed’s latest projects are “Malcolm and Me,” and “The Fool Who Thought Too Much,” both available at Audible.com. He is a Distinguished Professor at the California College of the Arts.

It didn’t take until Trump’s fourth presidential year for Black people to identify Trump as a racist. I certainly didn’t have to be educated about Trump’s bigotry. I referred to Trump’s followers as “a death cult” in 2016, a remark that drew copycats. Black people have been always aware of the danger; they are now arming themselves in case these “militias” act crazy.

But that the kicked-around were alert to where Trump was coming from even before his garish entrance into presidential politics doesn’t seem to have changed whom the opinion industry has rolled out to explain his reign. It took elite opinion writers a long time to call Trump a racist. And even after they turned, they still made excuses for the Trump cult right up to and after his loss.

This has reminded me of an article I wrote for Willie Hearst III’s Alta magazine. For it, I interviewed Terry Ashford, who at one time managed the great blues singer Big Mama Thornton. Her rendition of “You Ain’t Nothin’ but a Hound Dog” has a depth lacking in Elvis Presley’s version. As a Black queer woman she knew about the profound hurt, a hurt known by every individual or group that has been kicked around. This experience was foreign to Elvis Presley, who, as a white man, no matter how humble his origins, had more options. I went on to write a line in a poem about how Elvis Presley couldn’t make a growl like Big Mama. The growl that Toni Cade Bambara’s character Minnie in the overlooked masterpiece novel The Salt Eaters—overlooked because the literary establishment can tolerate only one or two Black writers at a time—makes as a reaction to how women were treated by the patriarchs who led the Civil Rights Movement. A growl that these white men of the opinion elite cannot pull off.

Though sections of the New York Times are beginning to look like Ebony magazine, the columns printed on the editorial page are dominated by privileged white men whose résumés are interchangeable, even though the token women, Gail Collins and Maureen Dowd among them, are better writers. These men and those like them rule the opinion pages of most of the mass media. While several studies have concluded that what unites Trump voters is the fear of sharing power with a diverse America (not “economic anxiety” or “political correctness” or fear of the “woke nation”), Thomas Friedman and others continue to call on someone who would heal the voters’ feelings of “humiliation.” They play editorial patty cake with Trump’s followers, who in the wake of his defeat roamed the countryside heavily armed, intimidating volunteer poll workers and poll watchers. In September, Friedman wrote that to babysit Trump’s haters, racists, and anti-Semites we should massage their feelings. “Humiliation, in my view, is the most underestimated force in politics and international relations,” he said. “The poverty of dignity explains so much more behavior than the poverty of money.”

Of course, Trump received votes from all classes of whites, including the “humiliated,” who seem to have enough money to spend on an arsenal, as well as the prosperous. Trump told his friends that he was going to make them rich, and true to his word, he gave them a beautiful tax cut.

Many white liberal commentators refused to budge from the notion that Democrats must reach out to Trump supporters among whom are climate crisis deniers, racists, anti-Semites, and every has-been broken-down bigot who has trod the hate circuit for decades. Some of them are named by the NAACP, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the Anti-Defamation League. Even in defeat, a defiant Trump threatens to stay put, and his millions of fans, his Trumpistas, promise to give democracy the finger for decades to come.

Friedman and David Brooks—who has palled around with race science quacks and congratulates whites with high fertility rates for moving from “vulgarity“—have been allowed to prattle on in the opinion pages and influence the national conversation. Once in a while, these Manhattan-centric pundits make a foray into the west. Brooks was chosen to cover Compton, a hip-hop hub. Did that trip change his mind about the cerebral abilities of Blacks?

The opinionmakers’ comments about the Latino vote also showed their lack of knowledge about the nuances of multicultural life and revealed their limited perspective. I watched as frustrated Latinx intellectuals and pundits sought to teach them to differentiate one group of Latinos from another, yet they insisted that Cuban Americans represented the Latino vote when Puerto Ricans in Florida supported Biden. Joe Biden likely received close to 70 percent of the Latino vote. One writer who has noticed the difference between the political attitudes of Cuban Americans and Latinos who supported Biden in New York, California, and the Southwest was Nanette Deetz, a Dakota, Cherokee, German American poet and journalist. She wrote: “Yes, all those Florida Latinx folks are the descendants of Batista’s regime who had the money to flee Cuba for Miami during the early 1960s. I happened to live in Cocoa Beach at the time, and there were so many immigrants from Cuba, all wealthy, all moving their wealth out of the country.”

The same white pundits made a similar error in 2008. There were doubts that Latinx people would vote for a Black candidate—the divide-and-conquer strategy from the playbook of classical colonialism. But Latinos had supported Obama when he ran for the Senate and they would again when he ran for president.

Another Times man, Bret Stephens, fell for almost every trick. His naiveté and ignorance about American history were on full display in his defense of the so-called “founding fathers.” Joining other vaunted official bestselling white historians and even President Trump’s criticism of the Times’ 1619 Project, he wrote:

As for the notion that the Declaration’s principles were “false” in 1776, ideals aren’t false merely because they are unrealized, much less because many of the men who championed them, and the nation they created, hypocritically failed to live up to them. Most of us, at any given point in time, are falling short of some ideal we nonetheless hold to be true or good.

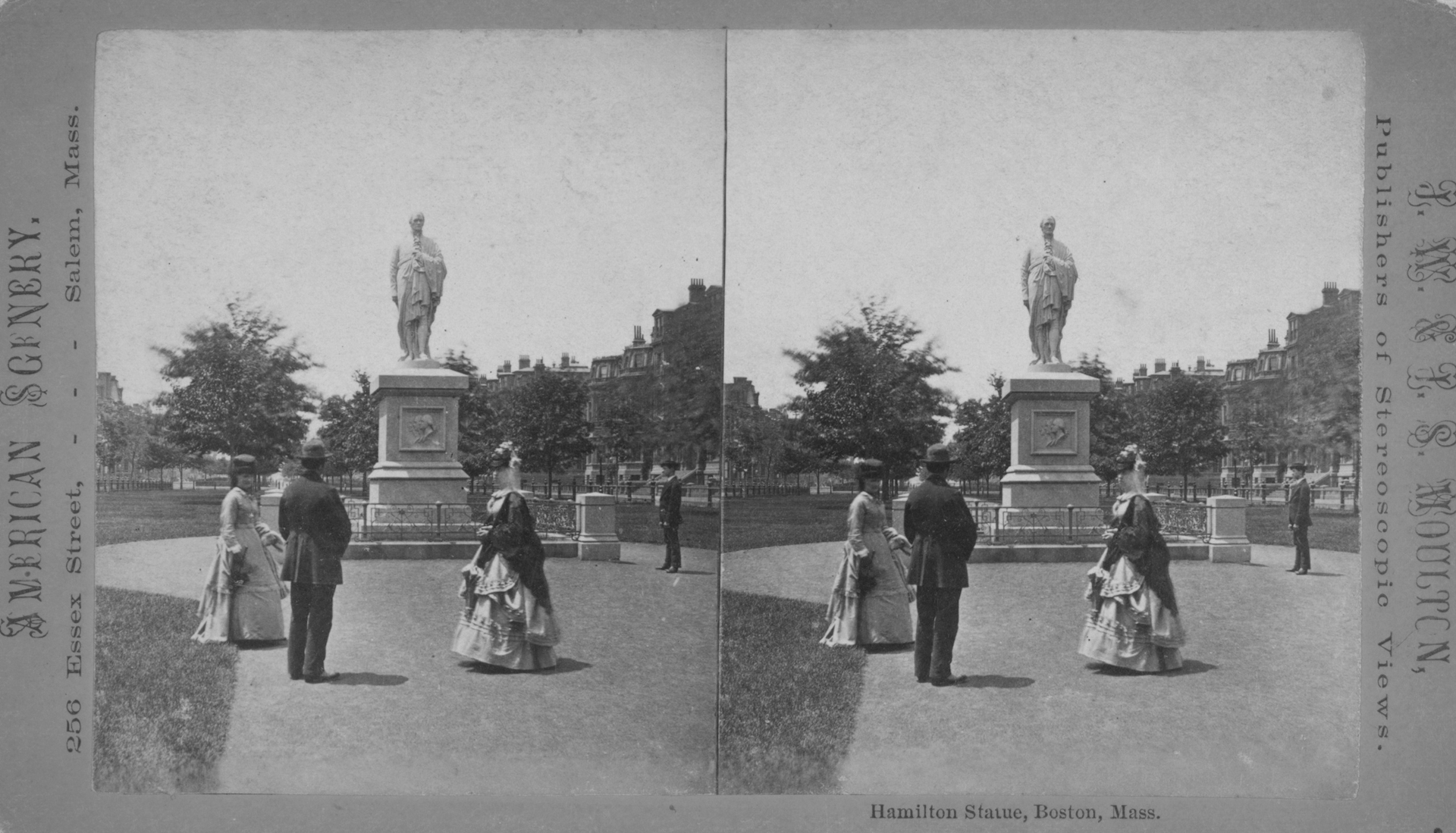

Enslaving and brutalizing African people and designing a blueprint for exterminating Native Americans, a plan advocated by Jefferson, Washington, and Hamilton: merely a matter of “falling short”?

Another critic of the 1619 report was Andrew Sullivan, who breezes by as a result of the awe that the Anglophile remnant of the New York elite still holds for things British. He championed The Bell Curve, which was littered with research from a “race betterment” outfit called the Pioneer Fund. One of the founder’s buddies was hanged at Nuremberg.

Once in a while members of the opinion elite do the model minority bit. Pitting one group against the other. Nicholas Kristof says we can learn from Hispanics, a column that amused Latinx scholars, because Latinx, like Asian Americans, are not monolithic. Though some Asian American groups have gained enough clout to challenge affirmative action at Harvard, where they wouldn’t be without the civil rights movement, poverty among some other Asian American groups is on the rise. The same holds for Latinx groups. Unlike the thousands of immigrants who’ve been caged by Trump, these print columnists seem confined intellectually to a kind of the first-class compartment of the New York-to-DC shuttle of the mind. We’ve had to wait four years for some of them to agree with us about the danger presented by Trump and his followers.

These are the people Bob Woodward referred to as “decent people.”

Like the men who—following their manifesto in novel form, The Turner Diaries—attempted to kidnap the governors of Michigan and Virginia? Decent people? Trump has sent well wishes to QAnon, whose ideas are reminiscent of the The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. “They like very much me,” he said. Decent people? And what about his telling the Proud Boys to “stand by“? Kyle Rittenhouse murdered two Kenosha protesters yet has received $2 million from “decent people” to pay for his defense, and his action has been supported by his leader, President Trump. Is Rittenhouse a decent person?

While some of these privileged opinion writers from Princeton and Harvard dawdle about the motives of those who hanker for a civil war, obviously ignorant of the outcome of the last one, some Jewish and Black leaders can now be seen as prophetic.

I’m not the first Black writer to challenge the inflammatory and racist opinions promoted by the media. Both villains of two of Charles Chesnutt’s novels, The Marrow of Tradition (1901) and The Colonel’s Dream (1905), are newspapermen. One promotes a riot and the other a lynching. In an excerpt from his poem “The Day and the War,” Black poet James Madison Bell, who lived from 1826 to 1902, criticizes Harper’s Weekly for its coverage of the Black Brigade, which fought for the Union.

The media is white-controlled, as is publishing. You can get a more accurate picture of Black and Brown life from those intellectuals and scholars who use Facebook than from the corporate media, including Hollywood, where their situation is defined by others. Though the opinion elite sneer at social media, outlets like Facebook have provided Black and Latinx intellectuals, scholars, and artists with tools that they are using to counter American history as presented by historians who belong to the Great-White-Men-On-Horseback school of history.

Like the affluent white male opinionmakers, these historians’ views dominate the textbooks read by millions of children and college students as well as the general public. Because of an upheaval in the discipline of history, women, Native American, Latinx, Black, and Asian American historians are countering the old myths and cover-ups that have attended traditional historian narratives. This prompted me to challenge the American Historical Society at their conference, to apologize for the smiley face that some of their historians have put on American history, and eliminate the face that expresses disgust. One of the characters valorized by historians is Robert E. Lee. Even Ken Burns, producer of the hymn to the Confederacy called The Civil War, said that Lee caused more American deaths than the Japanese.

Before she was killed, Elizabeth Brown Pryor, a white historian, was a member of a new, more diverse generation of historians. She recounts in Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters an episode that reveals the character of Lee. When fugitive slaves, a brother and sister, were returned to the Arlington plantation, Lee ordered them to be whipped. They were stripped to the waist. The sister was given 20 lashes, the brother was given 50. The overseer, Mr. Gwin, showing compassion, refused to deliver the beatings. Another man was called in and was instructed by Lee to “lay it on well.” After the beating, Lee then instructed the overseer to “thoroughly wash their backs with brine.” Lee believed that Blacks needed “painful discipline.”

Yet, in their official history, John Brown is the lunatic?

One of the arguments promoted by television historians, who defend such deeds as Lee’s, is that the slave masters were products of their time, which excludes the millions of inhabitants of those times who were opposed to slavery, including some slave masters themselves.

Slave owner General Phillip Schuyler was the father of Hamilton’s Angelica and Elizabeth who are depicted as progressives in Lin-Manuel Miranda’s musical. I have spoken publicly about the danger of the play. General Schuyler was the founder of the New York Manumission Society, an abolitionist outfit, while tracking down his runaway slaves. The myth of Hamilton as an abolitionist was detonated, not by a “stormy” writer like me but by the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site. This from a recent local article:

While some historians have made the case that Hamilton was an abolitionist or a reluctant slave owner, an article from the Schuyler Mansion claims otherwise.

“Not only did Alexander Hamilton enslave people, but his involvement in the institution of slavery was essential to his identity, both personally and professionally,” writes Jessie Serfilippi in a report titled “As Odious and Immoral a Thing: Alexander Hamilton’s Hidden History as an Enslaver.”

Ron Chernow, whose 2004 biography calls Hamilton an “uncompromising abolitionist,” a false idea that has generated a billion-dollar musical, said he was dismayed at the relative lack of attention to Hamilton’s antislavery activities.

Antislavery? Like when he sided with the French slaveholders when they were met by an uprising by slaves? Given Hamilton’s lifelong involvement in the slave trade and his seldom-discussed cooperation with the massacres of Native Americans, isn’t Chernow’s plea on behalf of Hamilton like giving brownie points to a serial killer for helping elderly women across the street?

I doubt whether this official report will face the criticism, much of it ad hominem and vitriolic, that I received in the New York Times, Broadway World, and even on NPR’s “Wait, Wait Don’t Tell Me,” for daring to question the musical Hamilton, which was based upon the false idea that Hamilton and the Schuyler daughters were abolitionists. Now that the script of my play, The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda, has been published, we’ll see whether it’s distributed to as many students as Hamilton. Though some say that I victimize Miranda in my play, those who have seen the play agree that he is a sympathetic figure. He was misled by a white power curriculum. So was I.

Those of us who have undertaken this pursuit of uncovering the truth feel like the character played by Kevin Bacon in the 1999 movie Stir of Echoes, in which he has a hunch there is a “corpse in the wall.” A new generation of intellectuals and historians, white, Black, Latinx, Native American, and Asian American, is dedicating itself to finding the corpse which represents all that was kept secret by state and corporate intellectuals. So much has been omitted by them.

For example, did you read anywhere in your textbooks that there were secessions within the secession, especially when the Confederates passed the Conscription Act of 1862, which exempted owners of up to 20 slaves from service, prompting many of the grunts to consider the war a rich man’s war? Ignorant Southerners in modern times have erected statues to mass murderers of Native Americans and Mexicans and practitioners of cruel enslavement of Africans, but up to 100,000 Confederate soldiers showed their devotion to the Confederate cause by going AWOL during the war. One of Lee’s generals commented, “If we could get back half we could win the war.” Nobody told me that there was a pro-Union sentiment in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, and that those white deserters and Black fugitives formed interracial gangs devoted to robbing the rich and feeding the poor.

Are many aware that thousands of their great grandmothers of Southern white women, on April 2, 1863, armed with “axes, knives, and other weapons,” confronted the Confederate army? The issue was food shortages. Shouting “bread of blood,” and led by Mary Jackson, a mother of four, and Minerva Meredith, the crowd dispersed only when Jefferson Davis threatened to have the army fire on them. Yet some contemporary Southern women support statues and place names honoring Jefferson Davis, who threatened to massacre their great grandmothers. Moreover, what would the white women who rose against the heinous Confederacy think of the contemporary white women who twice gave their votes to a sexist and misogynist? Trump convinced them that Mr. T and Mike Tyson were also coming out there to get them.

How about erecting statues to Mary Jackson and Minerva Meredith?

We know about Jackson’s role in removing Native Americans from their traditional homelands, but I’ll bet the historian who was in the news for defending Jackson never heard of the massacre of Blacks and Choctaw after they seized a Florida fort. Afraid that other slaves would get ideas from the slaves who’d escaped, he invaded Florida even though it was Spanish territory. He sent General Gaines to bombard the fort, resulting in “a terrible explosion that instantly killed 270 Black men, women, and children within the fort, the rest being mortally wounded out of the total 330 residents.” Insulting the chain of command, Jackson didn’t get permission from President Monroe before invading Florida. His over-the-top actions didn’t end there. As president, Jackson attempted to interfere with postal delivery—yes, him too—because he was upset about abolitionist pamphlets being distributed in the South. The Confederacy and slave owners like Jackson saw themselves as extending the idea planted by the founding fathers like Hamilton who believed that the purpose of government was to increase the assets of wealthy white men and that Blacks were private property no different from livestock. He accused the British of “stealing negroes from their owners.”

The Hamilton sales department, prodded by historian Annette Gordon-Reed, who is on the Hamilton payroll, abandoned the idea that Hamilton was an abolitionist. The sales pitch then became that Hamilton was opposed to slavery, which is contradicted by his support of the French slaveholders when the Haitians revolted against them. Now, Lin-Manuel Miranda, in what I have called “his Perry Mason moment,” says that he couldn’t include everything and had to cut. He implies that material about Hamilton’s slave trader activities had been extracted from the final script. Since the question of whether Hamilton was a slaveholder is central to Miranda’s musical, isn’t this like the scribes who wrote the Old Testament announcing that they wanted to include Genesis, but they couldn’t include everything? Lin-Manuel Miranda and Donald Trump had their opinions of key American personalities formed by the school curriculum. So did former US Rep. Steve King.

The critics of the ex-congressman, one of the most recent public figures to be subject to a national shaming, overlooked what King said about the origin of his white nationalism. He said that he learned it in school. So did we. A view of American history from different points of view is a welcome development. That way we find why Jon Meacham calls Jackson “imperfect” and why the Creek called him “a mad dog.”