Mother Jones illustration; Getty

Kamala Harris had certainly practiced for this moment. It was September 2019, and she was in the middle of a bruising primary for the Democratic nomination for president. After briefly peaking in the summer, when her first debate performance offered a memorable confrontation with Joe Biden that spawned many memes, Harris was now struggling to separate herself from the pack. Her biggest enemy, it turned out, was her past as a prosecutor.

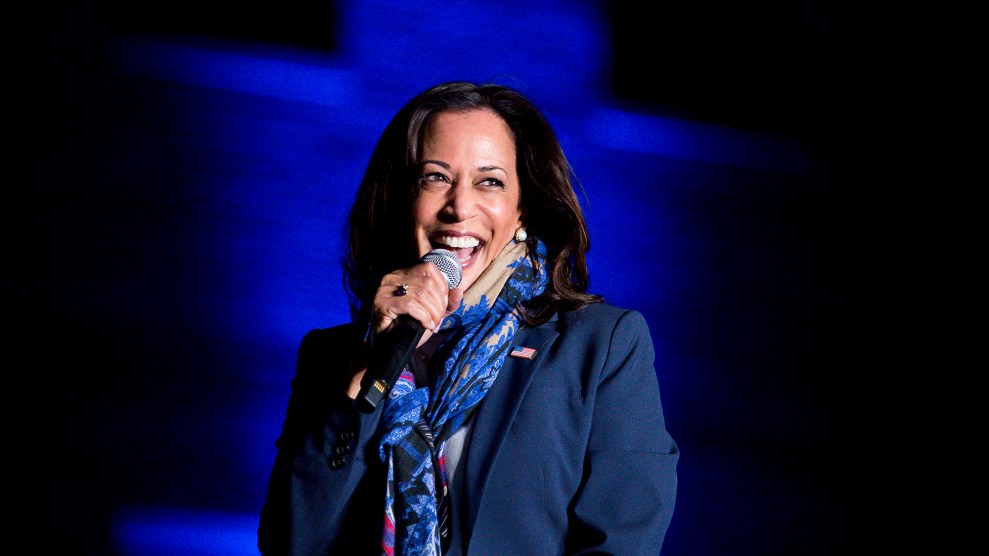

So when she took the stage in Houston for the third Democratic presidential debate, wearing a navy blue pantsuit and her signature set of white pearls, she knew what was coming. ABC News correspondent Linsey Davis, one of the few Black women to serve as moderator during the primaries, wasted no time grilling Harris on her newfound support of legalized marijuana and outside prosecutions of police misconduct.

“You’ve said that you’ve changed on these and other things because you’re ‘swimming against the current and thankfully the currents have changed,’” Davis said. “But when you had the power, why didn’t you try to effect change then?”

The top 10 nominees were all onstage together at Texas Southern University, a historically Black school, and Harris, the proud Howard University grad and sole HBCU alum in the race, should have had something of a home field advantage. Instead, the crowd at the debate erupted in applause, one of its loudest of the night.

“I’m glad you asked me this question,” Harris said once she was able to break through the applause. “I made a decision to become a prosecutor for two reasons: I’ve always wanted to protect people and keep them safe, and second, I was born knowing about how this criminal justice system in America works in a way that has been informed by racial bias.”

The answer was a well-rehearsed response aimed at reminding viewers that Harris’ identity as a Black woman took precedence over her job as a prosecutor. It was also a subtle nod to the driving force that had helped propel her to the national stage, first as a senator running for president and now as the first-ever woman of color to serve as vice president. That force, put simply, was Black women, who over the course of the past half decade have built an infrastructure of political action committees, nonprofits, and small donor networks to get Black women elected to public office on Democratic tickets.

Harris has become the most visible face of that movement, but she is not beholden to it. Now, as vice president, Harris will become the default leader of the Biden administration’s efforts to confront white supremacy, as the president outlined in his inaugural address. That challenge is twofold: tackling the kinds of political extremism that led scores of Trump supporters to raid the US Capitol, and tackling the kinds of policies, particularly in the criminal justice system, that have warehoused millions of Black people in the United States for years.

And those networks of Black women advocates are waiting with bated breath. Can a trailblazing but notoriously cautious woman lead on the nation’s most contentious issue?

As a political candidate, Harris had not always faced the fraught scrutiny that would characterize her run for president. In 2014, when she ran and won reelection as California’s attorney general, she was the pragmatic enforcer of laws in the biggest state in the union. Throughout her six-year tenure as AG, she went after big banks after the mortgage crisis, stood firm against marijuana legalization, and, importantly, stayed quiet during a cascade of high-profile police shootings of Black people that rocked the country.

Months before her reelection that November, a Black teenager named Michael Brown Jr. was shot and killed by a white police officer named Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, a working-class suburb of St. Louis. The shooting and the myriad injustices that preceded it led to waves of violence in the city and protests across the nation. Fiery images of protesters being tear-gassed and shot with rubber bullets by police flooded live television and social media. One rallying cry in particular captured the nation’s attention, tagged on social media posts and scrawled on handwritten protest signs: #BlackLivesMatter.

The hashtag and activism surrounding it were developed by three Black women, all organizers—Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi. Garza and Cullors were from Harris’ home state of California. With the help of burgeoning social media celebrities like DeRay McKesson, Shaun King, and Johnetta Elzie, #BlackLivesMatter became a national rallying cry. Garza, Cullors, and Tometi soon helped establish the Movement for Black Lives, a coalition of more than 50 Black-led grassroots organizations, and the Black Lives Matter Global Network, a decentralized network of organizers and activists based in several dozen cities across the United States and abroad.

“We understood Ferguson was not an aberration,” the organizers wrote about their formation in 2014, “but in fact a clear point of reference for what was happening to Black communities everywhere.”

What Ferguson showed Black activists like Jessica Byrd, a political consultant who would go on to work on Stacey Abrams’ gubernatorial run in Georgia and now helps lead the Movement for Black Lives’ electoral justice work, was that America was not a melting pot so much as a conveyer belt, affixing destiny based on race through decades of institutional policy and individual decision-making. The public could take to the streets, national opinion could be swayed, but who, exactly, would write new laws?

“It was just really, really, really clear that the national progressive infrastructure, including the Democrats, would not be able to hold the race, class, power-building narrative and strategy that would be needed to actually keep the demands of movement,” she told me.

On paper, Harris should have been a prime candidate to unequivocally become the face of such efforts. Her origin story starts with parents who met while protesting in the streets of Berkeley during the Civil Rights Movement. In college, she joined a prominent Black sorority with a focus on community service, and protested against apartheid in South Africa. But a career in law enforcement seemed to have clipped the wings of any radicalism that might have been there in the first place.

Harris did not say much publicly about the unrest. As leader of the country’s second-largest department of justice, she trod carefully. She stayed silent on a piece of legislation that would have required her office to investigate fatal shootings involving police officers, later saying that to speak out for or against the bill would have conflicted with her job of enforcing the law.

Instead, her office established a database that tracked police use of force in the state, including shootings. “Being ‘Smart on Crime’ means measuring our effectiveness in the criminal justice system with data and metrics,” Harris said in a press release at the time. “This initiative puts forward a common set of facts, data, and goals so that we can hold ourselves accountable and improve public safety.” This is the sort of pragmatic, in-the-weeds tactic that’s long been Harris’s trademark, but it doesn’t exactly lend itself to flashy slogans and big headlines. (Melina Abdullah, a pan-African studies professor at Cal State, Los Angeles, and an activist who leads LA’s Black Lives Matter chapter, would go on to tell the New York Times that the database was “very useful to us.”)

What wasn’t as useful: Harris withholding support for a bill that would have allowed special investigations into police shootings. “Where there are abuses, we have designed the system to address them,” Harris told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2014. Kevin McCarty, the Democratic legislator who wrote the bill, would later tell the Washington Post, “I think [Harris] had to walk a fine line being the state’s top cop and the practical purposes of such a position, and the fact that she had experience coming up as DA.”

When asked about this later during the presidential campaign by CNN’s Jake Tapper, Harris carefully noted that she had a policy of not weighing in on specific bills as attorney general. Turns out that was false: When the Washington Post later reached out to fact-check her claim, Harris’ team said she had misspoken and that she did take stances on certain legislation. What that meant was telling: One example was a bill that called for the execution of gay people—somewhat of a no-brainer in what is arguably the country’s most liberal state.

At the same time that Harris was carefully building up her political equity, progressive and radical organizers were shifting the conversation on criminal justice. No, Michael Brown, the boy who was killed in Ferguson, was “no angel,” as the New York Times infamously wrote, but perfection wasn’t a prerequisite for Black people to live, these organizers said. So Harris leaned into her personal narrative. In 2016, at a meeting on racial bias in policing in the immediate aftermath of a deadly police shooting in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Harris said, “As a prosecutor, my heart is breaking. As the top law enforcement officer in this state. And as a black woman.”

During the Democratic primary, however, this pivot was largely overshadowed by one of Harris’ signature policies as district attorney and attorney general. She had developed a program that would fine and, in a few instances, jail parents whose children missed school; while Harris expressed regret that parents were locked up under the law, the slogan #KamalaIsACop quickly took hold. Perhaps it came as no surprise, then, that a group of Black women activists, including Garza, Cullors, and Byrd, wound up endorsing Elizabeth Warren, calling her in a statement “a woman who is willing to learn, open to new ideas, and ready to be held accountable by us and our communities.”

The criticism didn’t keep Harris from digging into her personal history during the primary, though. During the first round of Democratic debates in June 2019, she confronted Biden on school desegregation busing and produced the standout moment of her campaign. “I do not believe you are a racist,” Harris prefaced her attack on Biden’s opposition to busing in the 1970s. “There was a little girl in California who was part of that second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day. And that little girl was me.”

That little girl grew up to join Biden on the Democratic ticket. Harris had long been a VP frontrunner months before Biden made it official in August 2020. The pandemic was disproportionately impacting Black people, and the summer of 2020 was punctuated by protests against the extrajudicial killings of Black people, namely Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. Harris took to the streets to join those protests and was pictured masked and socially distanced at a rally in DC. But she also had been working for months behind the scenes to quell the concerns of some of her loudest critics.

She introduced legislation in the Senate, first to boost funding for research on uterine fibroids, a condition that disproportionately affects Black women. Then she followed that up with a bill that would toughen laws against police chokeholds. She spoke out publicly against voter suppression. And she met privately with activists who had either publicly criticized her record as a prosecutor or withheld their support during the primary.

By summer, she offered up her personal biography in service of the moment. There she was in June, standing alongside Nancy Pelosi and other prominent Democrats donning traditional African kente cloth sashes—criticized on Black Twitter as “woke theater”—to unveil policing legislation. Days earlier, she was at a protest against police brutality in Washington, DC, wearing a nondescript blue baseball cap, just a senator and former presidential candidate among the people. “I was born a black child in America, the child of parents who were marching and shouting, just like all the folks who have been marching and shouting in the streets these last days,” Harris told a Post reporter at the protest.

The real work was done far away from the cameras. If she wanted to remain a viable pick for VP, she had to quiet the loudest criticism of her record that had come from Black women organizers and activists who took issue with her record. Garza, the BLM co-founder, lives in Oakland and was a grassroots organizer in San Francisco during Harris’ time as district attorney there. “It was an important and good meeting,” Garza later told the Post about one such effort in which Harris expressed regret about some of her previous positions as district attorney.

Harris’ run for president was her only unsuccessful political campaign. For the first time in her political life, playing it cautious didn’t make her a winner. It was undoubtedly a humbling lesson, and one driven home by the fact that her fiercest critics now will look just like her and share parts of her biography. These days, Harris’ remarks about racial justice are often tinged with personal anecdotes meant to convey the importance of having a Black woman in a position of leadership. But activists like Byrd, who have helped popularize the need for such leadership, don’t think that’s enough.

“Representation is unbelievably important,” Byrd told me. But, she cautions, “the future of Black politics is not just Black representation. It is accountability to people-powered movements who are asking for much more courage and vision.”